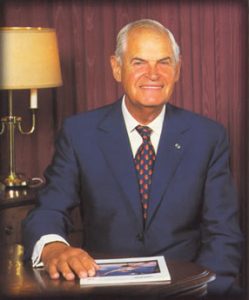

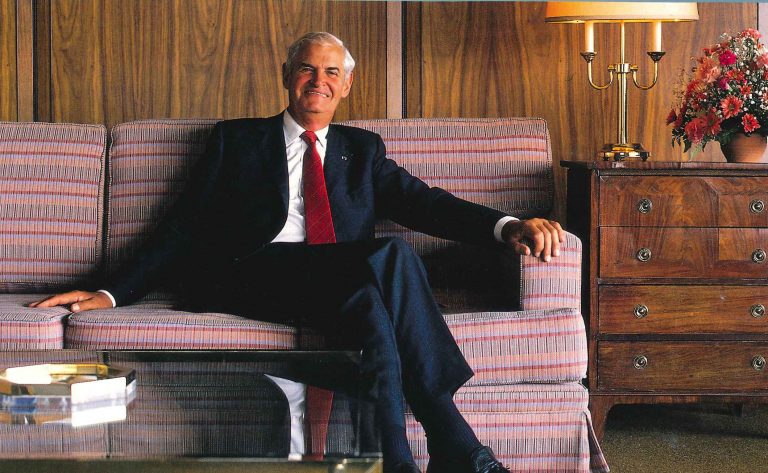

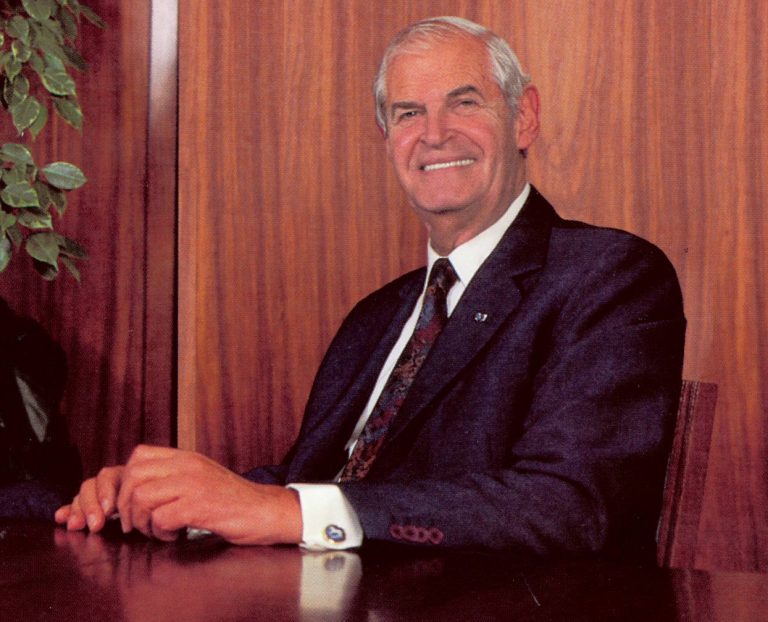

Dr John Maree

Dr John Maree – ESKOM CHAIRMAN 1985 – 1997

Mr. Johannes Bernardus Maree (John Maree) was appointed Chairman of the Electricity Council in 1985. He was a large, robust man with hands like shovels, a shock of white hair and steely smile. At that time, he was 60 years old – an age when most men consider starting taking things a little easier rather than taking on a new challenge of the magnitude that Escom posed. But then JB (John) Maree loved challenges.

EARLY YEARS

John Maree was born in 1924 in Middelburg, a rural town in the eastern Cape in a part of the Karoo known as the Camdeboo, where his father was the local dentist. It was not far from Graaff-Reinet, where a previous chairman Albert Jacobs, had been born almost a century before, and the area from which chairman J T Hattingh also hailed.

ACADEMIC YEARS

After completing his schooling in Middelburg and at Springs, he worked for five years as a learner salesman in a furniture store. He saved enough to enrol for a commerce degree at the University of the Witwatersrand. When he graduated in 1948, he was awarded the Alexander Aitken medal for the most distinguished graduate in the Faculty of Commerce.

BUSINESS CAREER

John Maree was a clerk at the Johannesburg Stock Exchange for three years and then joined the Union Free State Mining Corporation. He remained with the mining house until 1967.

Maree’s remarkable ability to identify the core issue in the most intractable and seemingly complex problems earned him a reputation as an effective trouble-shooter, shrewd businessman and exceptional communicator. After a brief spell as Deputy Chairman of Calan Limited, he came Executive Chairman of Rand Mine Properties in 1972, and was appointed to the board of the parent company Barlow Rand Limited in 1974. In 1979, he was seconded from Barlows to become Chief Executive of Armscor, at the request of the then Prime Minister, P W Botha. After a very successful spell at Armscor (he was named one of the top five executives in 1981 by the Sunday Times) he returned to Barlows, where he became Deputy Chairman.

INTRODUCTION TO ESCOM

The report by the Commission of Inquiry into the Supply of Electricity in the Republic of South Africa advocated a two-tier control structure for Escom. Soon after, John Maree was summonsed by State President P W Botha (1) and persuaded to take on the job as Chairman of the new Electricity Council.

Many regarded the job as impossible. However, the immense challenge and a sense of loyalty to do something worthwhile for his country drew Maree. Maree accepted, although very clearly on his own terms. Although the position did presumably not pay anywhere near what Maree was earning in the private sector, it made up for that in prestige, both locally and abroad. John Maree would put a personal stamp on the appointment, although officially he was the first non-executive chairman of Escom.

Maree was a man of ‘numbers’, as he liked to call financial and other management information. He stressed the dictum of ‘to measure is to know’ on just about every occasion, and instituted rigorous measurement and control systems. He was not satisfied until the reporting systems ran like clockwork, producing regular and reliable information. Once he understood the numbers, he was ready to make tough decisions.

THE ELECTRICITY COUNCIL

Legislation to restructure ESCOM was tabled during the first parliamentary session of the new tri-cameral Parliament in February 1985. The Electricity Supply Commission was replaced with a two-tier control structure comprising an Electricity Council and a Management Board. The council, as the controlling body of Escom, was financed separately by a levy on the sale of electricity, and was given the responsibility of formulating policy, strategic planning and high-level control. The board, however, was to manage ESCOM’s day-to-day affairs on sound business principles and within the guidelines, policy and objectives determined by the council.

The Electricity Council, consisting largely of customer and other stakeholder representatives, had perhaps more in common with a body of shareholder representatives than a board of directors. The Management Board fulfilled that function, emphasised by the fact that from 1992 onwards the members of the board were designated “Executive Directors”. The new structure gave a more businesslike approach to the organisation. Interestingly, it was a departure from the traditional British or American company structure and leaned towards the European (especially German) concept of governance

THE ESCOM YEARS

One of John Maree’s first actions on being appointed (and one that immediately earned him the admiration and respect of many ESCOM employees) was to embark on a journey around the country to speak to small groups of Escom managers – maybe a dozen people at a time. To the ESCOM people, this was unheard of; the chairman actually talking to them. Maree had no magic formula; he simply asked the same questions over and over: ‘What’s good about Escom? What’s bad about it? What shall we do about it?’ And ‘What is needed to do it?’ From this he deduced that in terms of producing electricity, ESCOM was actually doing a good job. Where it fell short was in terms of image. There was no pride left in working for an organisation that was lambasted in the press every day. The real problem was, he concluded, that Escom had lost touch with reality, the media, the customer and the political situation. It had gone on an expansion spree that the country did not need and could not afford, regardless of the consequences.

The Electricity Council appointed Ian McRae as Chief Executive of the Management Board. Maree brought in a young accountant as the financial executive. ‘Looking at the numbers’ became a key preoccupation in the organisation. He also appointed ESCOM’s first professional communications manager, as he regarded the whole question of how to handle the image of the organisation as crucial to the success of everything he was trying to do.

Seven priorities were defined; the need to have a mission and a strategy as a basis for all future actions was at the top of the list. The organisational structures needed to be radically revised. Planning, budgeting and control still needed urgent attention. Spending had to be drastically curtailed and tailored to the availability of money. People issues were next on the list, especially the fact that there were too many people and that there was no system to identify talent. The management of assets and working capital was also identified as a priority and last, but certainly not least, came the issue of image. Some fundamentals were spelt out on basic communicating principles. One of them was that the chairman was the only person who would do all the talking to outside stakeholders.

Maree and McRae spelt out ESCOM’s new corporate mission in one compact statement. Henceforth, ESCOM’s mission would be to ‘provide the means by which customer’s electricity needs are satisfied in the most cost-effective way subject to resource constraints and the national interest’. This mission statement was underpinned by a corporate strategy, which became the guiding principle for implementing the mission. It was ‘to develop ESCOM, as a business that maximises the value of its products and serves to South Africa’. To this was added a short, succinct ESCOM philosophy which read as follows:

‘We will follow a philosophy that asserts

• head office will be responsible only for formulation and dissemination of corporate policies and systems necessary for the health of the organisation and the collection and reporting of the irreducible minimum amount of information for the effective management of the organisation;

• that the line manager has the primary authority/responsibility/accountability to carry out the corporate mission and strategy and the corporate policies in an effective and responsible manner;

• the staff role is to support the line manager;

• positions will be filled by persons who are competent to discharge the duties of the position”

These simple yet powerful statements, collectively known as the mission, strategy and philosophy (MSP) became the mantra of the new ESCOM. Every group, division, department and section developed its own version of the MSP, derived from the corporate statement and tailored to its specific area of operation.

CUSTOMER SATISFACTION

A crucial shift in emphasis for the new ESCOM was the emergence of focus on the customers, as clearly spelt out for the first time in the MSP. John Maree had a simple, but effective, measure to gauge customer satisfaction. He counted the number of complaints he received as well as the compliments. When the compliments eventually started to outnumber the complaints, he knew that he was on the right track.

ESCOM AS BUSINESS

In 1986, a further change was legislated when the first chairman Hendrik van der Bijl’s cherished ‘no profit, no loss’ principle was scrapped. This put ESCOM activities on a proper business footing. This legislation also markedly reduced the Electricity Control Board’s previous extensive power over ESCOM. ESCOM no longer had to obtain licenses from the board to supply electricity. Although the board retained its control over the published list of standards ESCOM tariffs.

ELECTRICITY ACT AND ESKOM ACT

In 1987, legislation in the form of twin Acts – a completely revised Electricity Act and a new Eskom Act – was published. Whereas the 1986 legislation only scrapped the ‘no profit, no loss’ principles, the new Eskom Act completely did away with the Capital Development Fund and the reserve fund, which had been the cause of much criticism over the years.

The infamous funds were replaced with a set of simplified procedures with built-in controls over borrowing, and the accounting procedures were brought into line with generally accepted accounting practice. In terms of the new legislation, borrowings had to be approved annually by the minister, who could guarantee any contractual obligations. As before, all borrowings were a first charge against revenues and assets. Finally, most of the important recommendations first made by the Board of Trade and Industries almost ten years before were also implemented.

ESCOM was renamed ‘Eskom’ – a new name that no longer meant anything (except as a brand name) and was no longer an abbreviation for Electricity Supply Commission. John Maree deliberately wanted to create an image of the NEW Eskom – an Eskom of which its employees would once more be proud and with which its customers could once more be satisfied. It had already succeeded beyond his most optimistic dreams, but he was still far from satisfied that the organisation had achieved all it was capable of.

Eskom projected a different image. It was on the way to becoming an organisation that meant business. It was proud of the fact (and made this known) that it underspent its 1986 budget by a massive R200 million alone. Chairman Maree pledged that Eskom would in future keep the average electricity price increase at least two per cent below inflation. The organisation met this challenge with distinction.5 Eskom started the practice of delivering real value to its customers, thereby earning the respect of many of its fiercest critics.

STAFF REDUCTION

To create a new meritocracy, a system of performance management was introduced, in terms of which exceptional performance was encouraged and rewarded. As in the private sector, this meant that some executives received greater salary increases than others. Similarly, the less efficient and productive were increasingly being weeded out.

One of the most visible actions Eskom took was to reduce its bloated bureaucracy. When Maree took over in 1985, Eskom had 66 000 employees. When management presented its first budget to him it projected an increase to 72 000 people in 1986. Maree strode into the board meeting and announced that there was a mistake in the numbers. “Too few people?” management wondered. “Too many”, Maree said firmly. “Cut it by ten percent.” “No, cut the people by ten per cent. Sixty thousand.” Stunned silence. Then came feeble protests and murmurs rippling around the room. “Cannot be done. So much plant to commission. So much work to do. Chairman, you do not know this business. How can you just say ten percent?” “Well, it is a nice round number, so let’s just do it.” Bewildered disbelief. “Just do it.”

At the end of 1986 the number of employees was down to 60 800, and by the following year, another 4 000 had left. The bureaucracy started to look leaner and fitter. After five years, the 50 000 mark was reached, in spite of the fact that the amount of electricity produced and sold had grown by more than 20%. The cost impact was enormous and Chairman Maree could not help but feel pleased about the success of this first step in a business he did not know.

EQUAL OPPORTUNITY

Efforts were also made to turn Eskom into an equal opportunity employer. It instituted extensive training programmes to provide blacks with opportunities to obtain the qualifications necessary for advancement. Nevertheless, there were still many unskilled jobs that needed to be done, and which could not easily be upgraded. This was to become an area for special focus in years to come.

John Maree and Ian McRae made a highly effective team. Maree brought his political acumen and connections, his private sector sensitivity, energy and dynamism to the table, while McRae contributed immense vision, superb organisational abilities and an extraordinary degree of credibility within Eskom.

McRae spent an enormous amount of time and energy ‘managing by walk-about’ – meeting employees and executives fact to face to explain the changes and the culture change taking place. Every year, he personally met several thousand employees from all levels throughout the organisation explaining and reassuring them. In addition, every manager was paid a visit several times a year by Ian McRae and John Maree in person, in a series of meet-the-team meetings which were soon dubbed the ‘I&J’ show.

Maree had reason to believe that communications were running pretty well at the top, and the 1 000 managers and supervisors were well acquainted with the vision of the top team. By 1987 he saw the remaining challenge as getting the remaining 56 000 people – 40 000 of whom were blacks – to accept and understand the new approach.

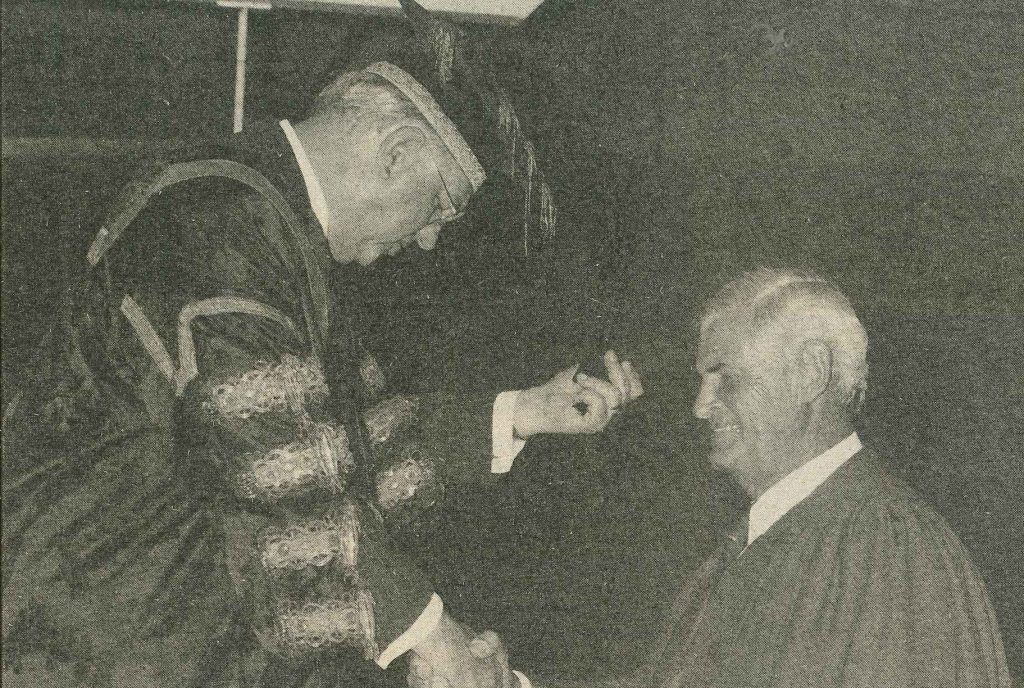

The University of Stellenbosch awarded John Maree an honorary doctorate in December 1987. He became known as “Dr. John” to most Eskom employees. President P W Botha, eighteen months later, awarded John Maree the Order for Meritorious Service which he added to his Star of South Africa awarded in 1985. In 1998, he became Chevalier of the French Legion of Honour.

RETIREMENT

John Maree retired as Chairman of Eskom in 1997. Mr. Reuel J Khoza was appointed to succeed him.

Notes

1. The constitution was amended in 1984, in terms of which Botha became an executive state president, combining the portfolios of Prime Minister and President into a powerful new office.

2. Although ostensibly only required to spend two or three days a week at ESCOM, he spent much more than that at Megawatt Park in the early years. But he never neglected his numerous other board responsibilities.

3. ESCOM’s numbers were inflated, with revenue and expenditure running into billions. Maree used to chide ESCOM management for rounding off numbers to the nearest million, maintaining that a million was still “real” money, enough to worry about.

4. This was based on the German model of an Uebersichtsrat (Board of Supervision) and a Geschalftsfuerung (Board of Management).

5. Nor was Maree the only one to keep the pressure on. For instance in 1988, management (supported by the Chairman) proposed a tariff increase of 12% for 1989 to the Electricity Council. The Electricity Council argued this down to 10%. The council won, and Eskom did not suffer the dire consequences that management had predicted would flow from so low an increase. It put a tremendous – and successful – effort on cost cutting instead.

6. I&J was the well-known brand name for Irving & Johnson, marketers of frozen fish products.

7. A large portion of blacks working for Eskom and in South African industry in general, estimated to be between 60% and 80% of the total, were functionally illiterate and were not able to speak or understand any language other than their own.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The source of this material is A Symphony of Power – The Eskom Story.

CHANGING WITH THE TIMES

When John Maree assumed his position as the first non-executive chairman of Eskom, he was well aware of the challenges that would face him immediately in making the utility profitable again. The task was monumental. However, in his 11 years at the helm, all challenges were handled with the same steely determination and drive to succeed.

Maree had already established himself as a strong leader in the business world and was the chairman of Barlow when the state president offered him the position of Eskom chairman for a considerable pay cut in 1985.

“I received a call from the president to say that Eskom was in big financial trouble and he asked whether I would want to come and sort it out, but remarked that he could only pay me pocket money.

“I told my wife Joy that it would be a very interesting experience and that it would open new doors for us. A few days later, I went back to the president and accepted the position.

“Eskom was facing some financial difficulties due to the fact that they had completely overestimated the growth in electricity consumption. They had started building five new power stations and then ran out of money.”

The first thing Maree did to address the financial difficulties was to meet with all the overseas investors. The result was that some projects were mothballed, while the remainder were completed. Eskom also adjusted its rates to give it a measure of financial breathing space.

One of the biggest decisions Maree had to make at the time was around the Majuba power station. It was one of the most expensive projects in the country’s history, but also boasted the most modern technologies.

“The board could not decide whether the project should be completed, so I made the decision to finish Majuba, which for three or four years was the worst decision I had ever made. We had overcapacity and here this big power station was coming out of the ground with no load on it.

“Everybody looked at me askance for a period because of this decision, but it turned out to be a really good one, because when we entered a growth phase again and put load on the station, it proved to be so efficient. We ran the station at around 80% efficiency and people were coming from around the world to see how we did it.”

After the big decisions around new build were addressed, Maree turned his focus to running Eskom more efficiently. He set out with the vision of running the best utility in the world with CEO Ian MacRae, who he describes as possessing an immensely competent technical mind.

As with any business he had been in charge of before, Maree immediately wanted to know who was in charge of finance. He created the position of internal auditor and appointed a young Mick Davis into this position. Davis started to measure everything in the utility in terms of cash flow.

“What had happened at the time was that there was a budget, and when the budget was overrun, they put it on the capital account. This meant that they were looking pretty good on the monthly expenses, but the capital expenditure was immense. So, we started measuring the business solely on the money going in and out. That really started turning us around in terms of knowing where we were going and what we could or could not afford.”

Maree also had to attend to the poor relations that existed between Eskom and the politicians. Maree addressed the issue by religiously reporting on a monthly basis to the two successive ministers, Danie Steyn and Dawie de Villiers, keeping them updated about all the inner workings of the utility. Eskom’s team also presented their position to parliament four times a year.

“We started running smoothly again after about five years,” says Maree. “When I arrived at Eskom, there were 66 000 employees. In the end there were less than 40 000. Because we had the capacity outages were unheard of.”

With this capacity, Eskom became the cheapest electricity supplier in the world and the envy of other nations. This, and efforts to build better relationships with clients, led to improved morale amongst the workforce.

“It was said that many people who worked for Eskom were reluctant to admit it to their friends. This was changing due to the cheap efficient supply of electricity, which gave us a big international advantage.” While Eskom was making these changes, the country was also going through change. With the dismantling of apartheid and the establishment of a new government, Eskom’s focus had to change again to benefit those who had been excluded before.

To support government’s RDP drive, Eskom undertook to electrify previously disadvantaged communities. At the peak of the programme, Eskom was electrifying 1 000 homes a day, leading to the electrification of a million homes in three years. This was achieved without any assistance from government and was financed in its entirety out of Eskom’s budgets. Fortunately, the efficiencies that were introduced beforehand made this massively expensive undertaking affordable.

“Until that stage, I had a saying that Eskom’s workers must pick up the money that is lying on the floor, in other words, be more efficient. Now we were financing a project where we were pouring money into electrification, with very doubtful revenue from it, and people were sceptical. However, we had a new environment and we had to adapt to it.

“Whenever I returned from an overseas trip, I made a point to talk to the president to tell him how we were being perceived overseas and about the difficulties we were facing internationally. With this information, I managed to persuade him to start electrifying the townships even before the end of apartheid. As things started to change I met regularly with Nelson Mandela, both individually and as part of a business team, to discuss what we were trying to achieve. It was clear from those engagements that we had to make our image acceptable to the new South Africa.”

One of the projects undertaken during his tenure that was particularly dear to Maree’s heart was education and training. It became apparent that the country was on the verge of experiencing a shortage in skills related to a proficiency in maths and science. While Eskom had training colleges, Maree wanted to take it further. He then approached professors at Stellenbosch university and asked them how long it would take to train an individual with matric, but without maths and science, to become proficient in those two disciplines.

“We employed around 25 youths with matric. They lived at the college and after one year, all of them passed maths and science, with three quarters of them passing on higher grade. From that it became clear that the problem was not with the children but rather with the teachers. We then decided to also train teachers in mathematics and science on a similar basis. Our influence was definitely positive.”

Through these and many other initiatives, Maree proved his worth in maintaining a strong link to Eskom’s innovative past and streamlining the company to deal with the challenges of the future.

Dr John Maree

At the peak of the programme, Eskom was electrifying 1 000 homes a day, leading to the electrification of a million homes in three years

“Whenever I returned from an overseas trip, I made a point to talk to the president to tell him how we were being perceived overseas”

“We had a positive influence as you should have as an important citizen of your country, which Eskom certainly is”

“Eskom was facing some financial difficulties due to the fact that they had completely overestimated the growth in electricity consumption”

Quotes from Dr Maree

“If you want ot be a patriot, if you want to be a good South African, if you want to contribute to the development of your country, you don’t have to go out there and find a course, just do the job that you do here at Eskom very well. Because with the cheapest electricity in the world, the best mining companies in the world, top industrial companies ,we can build a bigger economy.”

“The driving force that came through for us was in the first instance, run the business efficiently, get it better and better and keep reducing the price of electricity. The second one was to bring electricity to more people, more and more homes. And finally, to make the orgaisation look like South Africa. That drive to be able to reduce the price of electricity had a big impact on the total economy investment in South Africa. We started saying South Africa is going to have the cheapest electricity in the world. That was the big objective and we reached that in 1996. We then said South Africa could be the electricity value of the world as opposed to the silicon value that the Americans have, and electricity can attract energy intensive industries.”

John Maree now Doctor

On 10 December 1987, the University of Stellenbosch conferred an Honorary Doctorate in commerce on the chairman of Eskom, Mr John Maree According to professor Mike de Vries, rector of the university, Dr Maree is one of South Africa’s foremost businessmen. Over a period of about 40 years his contribution to South African mining industry and the distribution of electricity was of inestimable value. During this period he became known as a person who, with his particular brand of management skills, could tackle and solve the serious problems of a wide rand of organisations.

After obtaining his B Comm degree, Dr Maree joined Union Free State Mining and Finance Corporation in the early fifties and rose to managing director of the group. Subsequently he was chairman of Calan Ltd, chairman of Rand Mines Properties Ltd, and executive director of Barlow Rand with responsibility for the group’s property interests and electronics division. Dr Maree became executive head of Armscor in 1979 and returned to Barlow Rand three years later.

Dr Maree was chairman of the Electricity Council since 1985, and he also served director of several other companies and organisations. He served on the State President’s Economic Advisory Council and on the Energy Policy Committee of the Department of Mineral and Energy Affairs.

In recognition of his leadership, versatility and professional approach, Dr Maree has received numerous awards and tributes over the years. In 1981 the Business Times named him one of the five top businessmen of the year, and in 1985 he received the Star of South Africa from the State President in recognition of his contribution to the defence of South Africa.

John Maree’s contribution and success in the industrial sector is due to his ability to bridge the gap which often occurs between the government and the private sector. This requires a particular talent and adaptability in public relations to handle the various demand and expectations encountered in these scenarios.

Dr John Maree receives his Doctorate from the Chancellor of the University of Stellenbosch

President P W Botha