Electricity in South Africa - Early Years

The Encyclopaedia of Southern Africa records that “an electric device” was used in South Africa in about 1809. The first electric telegraph system, operated between Cape Town and Simon’s Town, was introduced in 1860. An early arc light was demonstrated in 1860 and the telegraph system was used for a time signal in 1861. In 1881, the local railway station in Cape Town was illuminated by means of electricity, and Port Elizabeth opened the country’s first telephone exchange in May 1882. From April 1882, electric arc lamps illuminated Cape Town’s Table Bay docks. The use of electric lights by the Cape Colonial Parliament in Cape Town is reported in the Cape Times of May 1882: “The House of Assembly continues to be lighted by the electric light and result has so far been highly satisfactory. The light is full, clear, pervasive and steady, and greatly improves the appearance of the chamber.”

The Diamond City, Kimberley, switched on electric streetlights in 1882 making it the first city in Africa to be illuminated in this manner. At this time, London still relied on gas lamps for street lighting.

Between 1884 and 1890 the use of electric motors, lights in mines, private lighting and an electric tram evolved. The first central power station was established in 1891.The discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand in 1886 led to Johannesburg installing its first electric lighting plant in 1889. This electrical power was generated by gas engines. An electricity reticulation system followed in 1891. Municipal electricity supplies started in Rondebosch in 1892, Cape Town city centre in 1895, Durban in 1897, Pietermaritzburg in 1898, East London in 1899, Bloemfontein and Kimberley in 1900, and Port Elizabeth in 1906.Hydroelectric power is reported to be first generated in 1892 and an overhead trolley-wire electric tram was in service in 1896.

In 1889, the company Siemens & Halske was granted the concession to supply electricity to Johannesburg and Pretoria. This company did not supply power until it also obtained a concession to transmit electricity to the mines of the Witwatersrand in 1894. This concession was ceded to The Rand Central Electric Works Ltd a year later. The Rand Central Electric Works Ltd proceeded to erect the first commercial supply undertaking at a site later to be known as Brakpan. Power from The Rand Central Electric Works Ltd was first generated in May 1897.

When mining companies began pumping water from deep level shafts, they realised that the power generated by small lighting plants was inadequate. They joined forces to build larger “central” power stations to supplement existing supplies of electricity. The Simmer and Jack mines were awarded the rights, in 1897, to supply electricity to five nearby mines owned by Consolidated Goldfields Group. A subsidiary company, the General Electric Power Company Ltd, was established to deal with this concession, a year later in 1898.

The General Electric Power Company Ltd commissioned a power station at Driehoek (near Germiston) that first supplied power in 1898. The use of electricity by the mining companies had been restricted to illuminating work areas and driving small equipment. However, as the exploitation of gold deposits became more complicated, the power requirements of the mining companies increased. As the gold-mining industry recovered from effects of the Anglo-Boer War, an adequate supply of cheap power became essential.

The notion of a central electricity undertaking gained the support of businessmen, engineers and others. This culminated in the establishment of the Victoria Falls Power Company Limited (VFP) on 17 October 1906. This company was registered in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). The VFP intended harnessing the power of the Victoria Falls to generate the electricity requirements of the expanding industries of the Witwatersrand and Southern Rhodesia. For technical and financial reasons this idea was abandoned. Three years after the establishment of the VFP, it was renamed the Victoria Falls and Transvaal Power Company Limited. The renamed company was still known as the VFP and based its entire operation on the exploitation of the coal deposits in the Transvaal Colony.

Shortly after the Anglo-Boer War, expert opinion recommended that large centralised power stations would supply more reliable and cheaper electrical power than small dedicated power stations. The VFP bought out The Rand Central Electric Works Ltd and the General Electric Power Co Ltd in 1906. A subsidiary company, the Rand Mines Power Supply Company, was formed by the VFP in 1908. This company was to supply electricity and compressed air to the Rand Mines Group and the Herbert Eckstein Group.

By 1915, four VFP thermal power stations Brakpan, Simmerpan, Rosherville and Vereeniging, collectively had a total installed capacity of more than 160 megawatts. A system control centre was established at Simmerpan. This has grown to be the national control centre which directs Eskom’s entire transmission network today. The rapid expansion of the VFP earned it the status of the largest power supply undertaking in the British Empire, at one stage. The VFP also pioneered long-distance transmission of high-voltage electricity under the severe climatic conditions of the Witwatersrand.

The Power Act introduced on 28 May 1910 by the Transvaal Colonial Government, limited the future existence of the VFP. The Act authorised the operational expansion of the VFP, but provided for the State’s expropriation of the company, or any other electricity undertaking, after a period of 35 years. The State viewed the provision of electricity as a public service to be placed under its authority.

As early as 1904, the administrators of the South African Railways advocated the electrification of the railway line between Springs and Randfontein. By 1912, the possible electrification of the railway line in Natal was being discussed. The line was to be powered by electricity supplied from a coal-fired power station in Natal. However, World War I interrupted these plans. Having determined that the erection of its own power station was necessary to electrify the lines, the Railways retained the services of Merz and McLellan, an eminent firm of consulting engineers based in London. Charles Hesterman Merz, a universally recognised expert in power station design and electrification of railways, visited South Africa in 1919. At the request of the South African government, he devoted part of his visit to the study of the country’s electrical power needs. The recommendations contained in Merz’s report, which was submitted to the government headed by Jan Christiaan Smuts in April 1920, were received favourably.

A government-appointed committee investigated the implications of the Merz Report. The findings of this committee led to government passing the Electricity Act in September 1922.

The Cape Town to Simon’s Town Electric Telegraph line – 1860

Electricity was publicly used in South Africa for the first time with the opening of the electric telegraph line between Cape Town and Simon’s Town on 25 April 1860. It was built for the benefit of shipping and commerce. The line itself was a single galvanised iron wire mounted on wood poles with porcelain insulators. The return circuit was via the ground.

(The Cape Monitor 1860-04-28; The Cape Argus 1860-05-15; Thos Maclear, Cape of Good Hope Government Gazette June 1861)

The telegraph line from Simon’s Town to Cape Town was the first electric line in South Africa and was declared open on 25 April 1860. This view was taken “on the road to Kalk Bay”.

(Photo: State Archives Ref. AG 4178 – The photograph has been touched up to make the line more visible)

This view of the telegraph line between Simon’s Town and Cape Town was taken near Muizenberg. The mountains at Fish Hoek and Simon’s Town are in the background.

(Photo: State Archives Ref. AG 13363 – The photograph has been touched up to make the line more visible)

An Electric Device

In an unpublished work, the author stated that this was a portion of voltaic pile. It was ostensibly used for healing, and amusement.

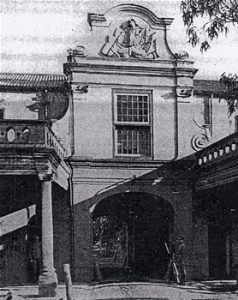

Demonstration of the First Electric Light

Mr. Charlton Wollaston, Engineer and Manager of the Telegraph Company, demonstrated an early arc light at a ball given in Cape Town on 1 August 1860. The ball was held at the Castle of Good Hope, the oldest colonial building in South Africa, in honour of Prince Alfred. Prince Alfred had come to the Cape to inaugurate the building of the Table Bay Harbour, which has now become the famous Victoria and Alfred Waterfront. The Cape Monitor of 4 August 1860 reported the light as “the first electric light which has ever been publicly exhibited in this colony”. The Castle yard was brilliantly lit, with “every corner for a few minutes as visible as in clear daylight”. Quite by coincidence, there was an eclipse of the Moon at the same time, which greatly enhanced the effect. (Cape of Good Hope Almanac 1860:16, 26; The Cape Argus 1860-08-02; The Cape Monitor 1860-08-04)

Telegraph line used for line signal – First Remote Control – September 1861

From September 1861 the Royal Observatory at Cape Town sent a daily impulse over the telegraph system to a time-ball, which was mounted on a mast in the vicinity of Table Bay. The impulse was sent at the instant of one o’clock and made the time-ball drop. Shipmasters used this as an accurate visual signal to check their chronometers. The impulse was also sent to the Naval Yard at Simon’s Town, and later to Port Elizabeth and East London when the telegraph line reached there. It was the first practical application of Remote Control in the country. A later time-ball tower is now a National Monument at the Victoria and Alfred Waterfront and firing of the noonday gun in Cape Town is still triggered by an impulse from the Observatory. (Cape Almanac 1853-1875; Reports of HM Astronomer at the Cape of Good Hope 1879-1902; Sir David Gill, A History and Description of the Royal Observatory, Cape of Good Hope, 1913)

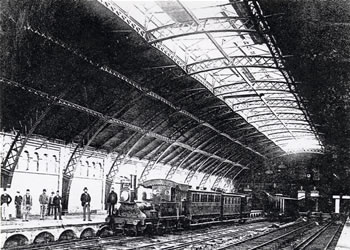

First public electric lighting- Cape Town Railway Station October 1881

Telephones Introduced

The first telephone line in South Africa is reported to have been from Roodebloem (Woodstock, Cape Town) to the Castle of Good Hope. This line was originally installed as part of the telegraph system. A telephone network was started in Cape Town with eleven sets of “microphone apparatus” in 1877. By 1880 there were doctors and others in Cape Town who had installed telephones in their private houses, and in 1881 a line was in use from the Docks to the Customs Building in Adderley Street. (Picard HWJ, Grand Parade, 1969:53; Mervyn Emms , The Advent of Electricity in the Domestic Scene, 1991:8; Ruth Prowse, The Cape Odyssey, Nov/Dec 2003)

The first telephone exchange in South Africa was installed at Port Elizabeth in 1881 and had 25 lines. There were 44 subscribers in 1882. Cape Town had an exchange with 50 subscribers in 1884. Pretoria had a telephone service from 1890 and Johannesburg installed an exchange in 1892-3. (The South African Mining Journal Oct 1892:35; Shorten, Cape Town, 1963:145; Mervyn Emms, The Advent of Electricity in the Domestic Scene, 1991:8; Robin Louwrens, The Cape Odyssey Jul/Aug 2003)

The De Beers Diamond Mines at Kimberley were using electric bells for signalling in 1887 – one of the advantages was that the wires could be carried around corners!! In 1888 these were supplemented by a series of telephones at the shafts and engine houses. (Inspector of Mines Reports G.28-1888 and G.22-1889)

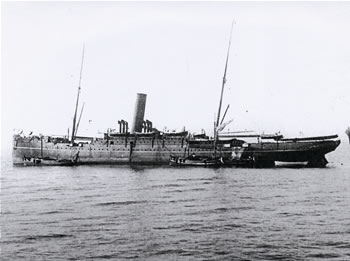

First commercial Arc Light seen in South Africa – Cape Town 1880

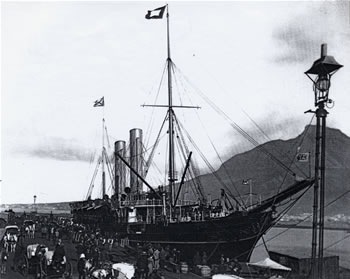

The Royal Mail Steamer “Trojan” arrived in Table Bay on her maiden voyage on 10 June 1880. She was fitted with a single arc light in the grand saloon and was only the second vessel in the world to be fitted with an internal electric light. Power for the light was supplied from batteries and a four horse power engine. Citizens flocked to the docks to see it. The Trojan served as a hospital ship during the Boer War. (The Cape Argus 1880-06-12; Crutchley Comdr. WC – My Life at Sea, 1912:201-203)

First Experimental use of ARC Light – Kimberley, August 1881

The French Mining Company experimented with a 300 candlepower “Lontin” arc lamp at the Kimberley Mine in August 1881. The Daily Independent of 15 and 18 August 1881 described it as “magnificently brilliant, somewhat resembling the light of the sun”. [Six Lontin lamps, supplied by French engineers, were used to illuminate the Gaiety Theatre in London in August 1878. This was the first public building in England to be electrically lighted. (Parsons RH, The Early Days of the Power Station Industry, 1940:3-4; History of Technology vol. V, Oxford 1978:211)

The Government Inspector of Diamond Mines, WCC Erskine, stated that in 1881 “the electric light was introduced for mining operations in the Kimberley Mine, where it was used in the claims and on the margin at the delivery boxes. It was found to be an immense improvement on the old style of lighting by night, viz. paraffin tins filled with waste saturated with paraffin oil”. (Inspectors of Diamond Mines Annual Reports G.27-1882:5, G.22-1889:5)

Table Bay Harbour Arc Lights – April 1882

From 25 April 1882, the Table Bay Harbour was successfully and brilliantly illuminated with sixteen “Brush” 2000 candlepower arc lights, identical to those still being installed in the streets of Kimberley. The number of lights was increased to twenty-two from 3 October 1882. In the Annual Report to Parliament for the year 1882, the Harbour Board reported: “The light has proved of great service, not only in minimising accidents, but in facilitating the working of vessels at night”. The building where the dynamo was first installed still exists at the Victoria and Alfred Waterfront and is known as “The Pumphouse”. It is still in use for pumping water from the Robinson Dry Dock, which is one of the oldest in operation in the world. (The Cape Argus and The Cape Times 1882-04-24; Cape Colonial Parliament – Harbour Board Report for the year 1882)

First Incandescent Lights – Hall used by House of Assembly, Cape Town, May 1882

“Edison” incandescent lights [a prototype of our modern household filament globe] were installed in the Banqueting Hall of the Good Hope Lodge at Cape Town in 1882. This was the official venue of the Cape House of Assembly from 1854 to 1884. The hall was publicly lit by electricity for the first time on 10 May 1882. The Cape Times of 11 May 1882 reported: “The House was illuminated by the beautifully bright and steady glow of the forty-four lights placed along the walls… There was a large attendance of the public in the House…and much satisfaction was expressed alike by members and spectators with the effect produced by the bright, soft and penetrating light”. As a result of the success of these lights the Government decided to install electric lights instead of gas lighting in the new Houses of Parliament, opened in 1885. (Cape Times 1882-05-11; Kilpin R, The Old Cape House 1918:25)

Kimberly Electric Streetlights – February to September 1882

Mrs Cornwall, Mayoress of the Diamond City, Kimberley, started the engine to light up the first electric streetlights in South Africa at a formal trial on the evening of 15 February 1882. These were 2000 candlepower “Brush” arc lamps. Initially the lamps threw out a brilliant light at the Market Square, but they had apparently been damaged in transit and failed later that same evening. Nine lamps were repaired within a few days, but it was not until 1 September 1882 that all sixteen of the first circuit of lamps were working satisfactorily and were accepted by the Town Council. At this time, Cape Town and London still relied on gas lamps for street lighting. (Original Minutes of the Kimberley Town Council Lighting Committee 1881-1882 [National Archives Ref. 3KIM/1/2/1//1/1]; Diamond Fields Advertiser and Diamond News, Oct 1881 to Sept 1882).

The Introduction of Electric Motors

A small electric motor was demonstrated at the South African Industrial Exhibition held in Cape Town in August and September 1884. About 1889, a 1/2 horsepower motor worked the sewing machine in the Trimmer’s shop of the Railway workshops at Salt River, Cape Town. (Harbour Board Report 1884 [G.40-1885]; Supplement to South African Commerce and Manufacturers’ Record, February 1914; Pask TP, SA Railways and Harbours Magazine, May 1922:421)

The Government Inspector of Mines reported for the year 1891 that at the Kimberley Mine “electric motors have been used underground for various purposes”. At the De Beers Mine “electric motors are used for pumping from wells, and sawing timber at surface, and for hoisting, pumping, and driving ventilating fans underground”. (Government Inspectors of Mines Report G.27-1892:4-7)

By the turn of the century, when the Kimberley Central Power Station was being planned, a power distribution of about 2,5 MW was estimated. By June 1902 the gold mines on the Witwatersrand had installed 634 motors of a total rating of almost 12 MW. (De Beers Consolidated Mines Annual Report 6/1901:11; Annual Reports of the Transvaal Mines Department)

Underground Electric Lights in the Mines- Kimberley 1887

Incandescent electric lights were tried underground at the Kimberley diamond mines by way of experiment in 1887. The results were “highly satisfactory”. Underground lighting was at first by means of tallow candles and paraffin lamps. If a “mud-rush” occurred, all open flames were immediately extinguished by the accompanying blast of air. Many miners lost their lives by being trapped and buried in the mud. The electric lights were not put out and enabled the men to escape. (Government Inspectors of Mines Reports G.28-1888:17-18, G.38-1894:10)

Private Lighting Plants – From 1889

There were several wealthy citizens who had their own electric lighting plants at their residences before 1900. Among these were Charles Rudd (Newlands, Cape Town), George Moodie (Rondebosch, Cape Town), Jimmy Logan (Matjesfontein), and Sammy Marks (near Pretoria). (Cape Times 1891-05-15, Cape Argus 1892-04-25, Toms RN, Logan’s Way 1997:23; A Symphony of Power 2000:15)

Battery Operated Electric Tram

A battery-operated electric tram was run in Kimberley in 1890. It was not very successful, mainly on account of the limited capacity of the batteries. Mules had to be used when the batteries failed. After an accident in 1896, the tram was withdrawn from service. (SA Engineer and Electrical Review 1941:35; Roberts B, Kimberley: Turbulent City 1976:239; Sabatini R, Kimberley Tramways 1887-1985:7-8)

First Central Power Station – 1891

In 1888 the Table Bay Harbour Board in Cape Town came to the conclusion that a “central station [supplying] public or other buildings by the means of transformers” would be more efficient than a number of individual lighting plants. This led to the Harbour Board building, in 1891, what constituted the first central power station and distribution system in South Africa. The plant installed was a 200 horsepower [150 kW] engine and dynamo with two boilers. An alternating current machine also supplied power at 2000 volts. In addition to the harbour area, among the buildings supplied from this station were the New Somerset Hospital, Royal Observatory, Public Library [now the National Library], Houses of Parliament, Old Somerset Hospital, Cape Town Railway Station, “New” Post and Telegraph Office and the Grand Hotel. Of these buildings the first four still exist. In 1903 the power station was superseded by a larger station. The latter building, including the original engine room crane, still stands at the Victoria and Alfred Waterfront and was known as the “CD Wherehouse” in 2005. It was being used as a restaurant called the “Planet Hollywood”, when a pipe bomb exploded on 25 August 1998, killing two and injuring 26 people. (Harbour Board Reports 1888-1903; Cape Argus 26-27 Aug 1998; Uys I, Cape Town: A Journey Through Time 2004:99)

Lighting plants were built at Rondebosch (Cape Town) in 1892 and at Wynberg (Cape Town) in 1893. The City of Cape Town commissioned a central station in 1895 and the Cape Town City Tramway Co another in 1896. Pretoria and Johannesburg also had small lighting plants in use in 1892. A “new” Lighting Works was installed in Pretoria in 1897, The Rand Central Electric Works at Brakpan was commissioned in 1897 and was the first public utility central power station to be constructed in South Africa and the first to transmit power at 10 kV. The Driehoek Power Station at Germiston started generation in 1898. The De Beers Consolidated Mines at Kimberley commissioned a Central Station in August 1903, at which the first 1 MW turbines in South Africa were installed. There were also other lighting plants and small central stations built at the end of the nineteenth century (see below). (Cape Argus 1892-04-20&25; Wynberg Times 1893-07-29; The Cape Times 1895-04-15; The Electrician, Dec 1897:291; SA Mining Journal, Jan 1898:369, Mar 1898:524-5; Machinery, Sep 1899:609-10; Robertson GM, De Beers Central Power Station, Journal SA Institution of Engineers, Aug 1913:1-25)

Electricity Reticulation System

An electricity reticulation system is defined as “a much more elaborate scheme than a few street lamps” in A Symphony of Power – The Eskom Story.

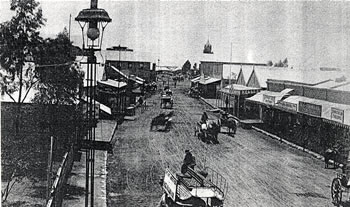

The discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand in 1886 led to Johannesburg installing its first individual electric lighting plants from 1889.1 The Johannesburg Lighting Company, which at first supplied gas for lighting, commissioned two dynamos driven by small gas-engines, for street arc lighting in June 1892.2 Johannesburg was not granted a Town Council until October 18973 but in 1896 Hubert Davies, one of the best known pioneer electrical engineers in South Africa, was busy laying out a complete system of distribution mains for the supply of electricity to practically the whole of the town.4 In Pretoria a limited liability company supplied lighting in 1892 on behalf of the Sanitary Board.5

- Machinery 1 January 1896 p.134-5

- Shorten JR, The Johannesburg Saga, 1966 p.599

- Johannesburg - One Hundred Years, Chris van Rensburg Publications 1986 p.22

- Hubert Davies, In: Machinery, 1 February 1896 p.162

- Machinery 1 September 1899 p.610

Public/Municipal Supplies of Electricity – March 1892 Onwards

Although the streets of Kimberley, the Table Bay Harbour and the House of Assembly were lit by electricity in 1882, it was to be ten years later before other municipalities introduced electric streetlights. The Cape Argus of 25 April 1892 reported that by March the “smoky old oil lamps for lighting the roads in the Rondebosch Municipality [in Cape Town] have been entirely replaced by electric incandescent lamps…much to the satisfaction of the residents of this suburb… The Moodie Fountain…on the main road carries four lamps… The circuit of lamps is about five miles [8 km] in length”. The circuit was initially supplied from the late George Moodie’s private plant until the generating plant at the Liesbeeck River in Rondebosch was ready. [The Moodie Fountain is now called the Rondebosch Fountain and has been proclaimed a national monument. It still functions as a streetlight, but with a modern globe]. James Bisset, Mayor of Wynberg, Cape Town, turned on electric streetlights from a central station at Wynberg, in what is now named Electric Road. The opening ceremony was held on 22 July 1893. (Original Minutes of the Rondebosch Town Council [National Archives Ref. 3/RBH/2&144]; Cape Argus 1892-04-20&25; Original Minutes of the Wynberg Town Council [National Archives Ref 3/WBG/14&21; Wynberg Times 1893-07-29)

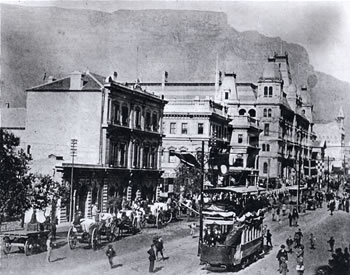

It was not until nearly two years later, on 13 April 1895, that Mrs Smart, Mayoress of Cape Town, switched on electric streetlights in the city centre. The generating station, on the banks of the Molteno Reservoir, has been proclaimed a national monument. (Cape Town Mayor’s Minute, 1895; The Cape Times 1895-04-15)

Although a concession for lighting Pretoria by electricity was granted in 1889, electric streetlights were not switched on until 10 June 1892. (JJN Cloete, doctoral thesis: “Die ontstaan en ontwikkeling van die munisipale bestuur en administrasie van Pretoria tot 1910” [The establishment and development of the municipal management and administration of Pretoria to 1910], Archives Yearbook for South African History, 1960 page 58)

The discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand in 1886 led to the founding of Johannesburg. The Cape Argus of 25 April 1892 reported: “Johannesburg April 23rd. The Sanitary Board yesterday afternoon decided to petition the Government to grant a subsidy of £15000 towards lighting the town”. Two months later, on 23 June 1892, the streets of Johannesburg were first lit by electricity. However, the first installation of the electric light in Johannesburg had been made in 1889, at a building known as “The Amphitheatre”. John Hubert Davies, one of the best known pioneer electrical engineers in South Africa, also erected a generating plant at the Jumpers Mill later in 1889. In 1891 a small dynamo was put down as an experiment at the Gas Works of the Johannesburg Lighting Co. (Interview with Hubert Davies, In: “Machinery” 1896:134&162-3; Official South African Municipal Yearbook 1911:324; Shorten JR, The Johannesburg Saga 1963:599)

Mrs Payne, the Mayoress, switched on electric streetlights at Durban during the opening ceremony of the new Municipal plant on 22 June 1897. The ceremony was a feature of the Diamond Jubilee celebrations of the 60th year of the reign of Queen Victoria. However, the Town Hall had been illuminated by incandescent lamps in 1888 and the Durban Harbour Department had installed a lighting plant at The Point in 1892. (WPM Henderson, Durban: Fifty Years Municipal History 1854-1904:172-3; Pask TP, In: SAR&H Magazine, May 1922:422-4)

At Pietermaritzburg the electric light was demonstrated in the Market Building in 1886. The first electric plant installed was a 30 kW alternator for lighting the Town Hall. It was started up on 1 April 1896 and a few private consumers were also supplied. A municipal electricity supply was made available from 1 July 1898. (The Electrician 1905/06:407; Electrical Review June 1906:902; Official South African Municipal Yearbook 1912:389; Eighty Years: The History of the Association of Municipal Electricity Undertakings (Southern Africa) c1996:8)

The Mayor, Capt. WC Jackson, switched on the first twelve electric streetlights in East London at a ceremony on 5 October 1899. Altogether 20 arc lamps and 283 incandescent lamps were originally installed. [See West Bank Power Station]. (Daily Dispatch 6 October 1899, Evening Edition; East London Centenary Programme 1848-1948)

Bloemfontein first supplied electricity to residents in November 1900. This was during the Boer War and the supply was under control of the military. (Electrical Review June 1906:902; Official South African Municipal Yearbook 1912:Table p340; The South African Electrical Review Dec 1946:27; Eighty Years: The History of the Association of Municipal Electricity Undertakings (Southern Africa) c1996:8)

Kimberley has the distinction of having the first electric streetlights in South Africa (although the Table Bay Harbour had the same “Brush” lights and at the same time – see Table Bay Harbour arc lights, above). A municipal power station to supply private houses and shops was formally opened by the Mayor, Mr Oliver, on 15 October 1900. Delivery of the machinery had been delayed eight months as a result of the Boer War. (Diamond Fields Advertiser 1900-10-19)

At Port Elizabeth, the “Brush” Electric Light and Power Company gave an exhibition of the arc light in October 1882. However, the electric light was not accepted by the ratepayers. Electric trams were in operation in 1897, but it was not until 1 May 1906 that the Mayor opened the Municipal Electricity Works. (Eastern Province Herald 1882-10-16&18; Original Minutes of the Port Elizabeth Town Council, Archives Ref 3/PEZ/1/1/1/17-21; E Poole, The Electrical Review, June 1906:903; Official South African Municipal Yearbook 1912:392)

Overhead Trolley – Wire Electric Trams

The first overhead trolley-wire operated electric trams were taken into service at Cape Town in 1896. The official opening date was 6 August, although Members of Parliament and other VIP’s had been taken on demonstration trips on 13 July. The Cape Town City Tramway Company built its own power station, which was at Toll Gate in the suburb of Woodstock. It had a much larger capacity than the Municipal station in the city, opened the previous year. (The Cape Argus 1896-08-06; Machinery, Sept 1896:327, Oct 1896:17-18; Coates PR, Track and Trackless 1976:89)

The Cape Electric Tramway Co opened a tramway in Port Elizabeth on 16 June 1897. The East London Municipality inaugurated their electric tramway on 25 January 1900. In 1901 the Camps Bay Tramway Company in Cape Town opened a line from Sea Point to Camps Bay, and in 1902 a line from Camps Bay to the city over Kloof Nek. A power station was built at Camps Bay where two 400 kW dynamos were erected. The route over Kloof Nek is now the Camps Bay Drive and the power station has been converted into a theatre. (Daily Despatch 1899-10-06; The Electrician, June 1903:299-302; E Poole, The Electrical Review 1906:903; Official South African Municipal Yearbook 1911:362; Coates PR, Track and Trackless 1976:118-9)

Electric tramways were inaugurated at Durban on 1 May 1902, Pietermaritzburg on 2 November 1904, and Kimberley-Alexandersfontein on 22 April 1905. (Henderson WPM: Durban: Fifty Years Municipal History 1854-1904; The Electrician Dec 1904:444; E Poole, The Electrical Review 1906:903; Sabatini R, Kimberley Tramways 1887-1985:12)

Horse-drawn trams were in operation in Johannesburg in 1891. From April 1895 the Johannesburg City and Suburban Tramway Co Ltd. made repeated applications to electrify the routes but President Paul Kruger’s government refused to grant a concession on the ground that “farmers would lose the sale of their forage”. Electric trams were not in operation in Johannesburg until 14 February 1906, nearly ten years after they were running in Cape Town. Electric trams were taken into service in Pretoria from November 1910. (SA Mining Journal, March 1898:515; The Electrician, Aug 1898:243, June 1900:274; Official South African Municipal Yearbook 1911:361; Johannesburg: Seventy Golden Years 1886-1956:403; Johannesburg: One hundred Years 1886-1986:98; Shorten, The Johannesburg Saga, 1963:601)

Hydro-Electric Power

Two 150 kW generators were commissioned by the Cape Town City Council in April 1895 on the banks of the Molteno Reservoir. The dynamos could be driven either by steam or water power. Water was supplied from the Woodhead Reservoir on Table Mountain, even though the reservoir was not officially completed until 1897. For the year ending 30 June 1896 the plant was run by waterpower for 2590 hours and by steam for 691 hours. It became the first hydro-electric station in South Africa. (Cape Town Mayor’s Minute and Annual Reports of the Electrical Engineer, 1895-97).

Gold had been found in 1873 at Pilgrim’s Rest in the Eastern Transvaal (now Mpumalanga). Two small [6 kW] hydroelectric generators were in use at the Pilgrim’s Rest gold mines in 1892 and another one [45 kW] in 1894. In 1896 a hydro generating station was built at Brown’s Hill using two Escher Wyss Girrard impulse turbines coupled to Siemens 160 kW alternators. A second hydro station was built further downstream and named Jubilee Power Station. An Escher Wyss Francis turbine and a Siemens 150 kVA alternator were installed. These sets were among the first three-phase alternators installed in the country and were used to power the first electric railway (excluding demonstration prototypes on the Witwatersrand in 1892). The railway transported ore to the reduction works over a 12 mile length of track using two 19 kW locomotives. (D Vermeulen, In: Elektron 8/2000:6 and Sparkling Achievements, Highlights of Electrical Engineering in South Africa, 2001:10-11)

Electric Railways

The first railways to be electrified in South Africa were as follows:

[excluding prototypes demonstrated by Hubert Davies to the gold mines in 1892 (D Vermeulen, in: Elektron 8/2000:8), the Tilling-Stevens petrol electric principle on the “Reef” early 1900’s (Pask TP, In: SA Railways and Harbours Magazine, May 1922:425) and the Kimberley-Alexandersfontein “Electric Railway”, which was later classified as a tramway (Sabatini R, Kimberley Tramways 1887-1985:12)].

1897 Mining: Pilgrim’s Rest (D Vermeulen In: Elektron 8/2000:6; see “Hydro electric power”) 1924

Main line: SA Railways Glencoe to Pietermaritzburg (see Colenso Power Station) 1927

Suburban line: SA Railways Cape Peninsula (see Salt River Power Station)

Steam Turbines and Gas Turbines

Up to the end of the nineteenth century the generators of all steam stations in South Africa were driven by reciprocating piston engines. Overseas, the steam turbine was at that time proving itself far more suitable for electrical power generation. It was much more compact and the steam consumption was less. The higher speed was also a big advantage. At about the same time, there were some engineers who were convinced that the end of the steam age had arrived and that gas engines would be the prime movers of the future. It was said that gas plant was simpler than steam and required less skilled labour. Little more than half the coal was required and less than half the amount of water of a steam plant. In 1904 the Johannesburg Town Council placed orders for three gas engines of 1000 hp each and five of 2000 hp. These sets proved to be a most costly disaster and the whole of the plant was rejected in 1908. Steam turbines were installed instead. (Johannesburg Town Council – Minutes of meetings 1903-1908; South African Mining Journal, Nov 1914:167; Dobson JH, The Johannesburg Municipal power Station, in: Journal of the SA Institution of Engineers, May 1916:216-221)

The first steam turbo-generator in South Africa was a Parsons 50 kW set installed by the Cape Peninsula Lighting Co at the Wynberg Central Station, Cape Town, in 1901. The building still exists in Electric Road and is presently (2006) being converted into apartments. Three 135 kW Parsons turbo-generators were installed by the same company at the Claremont Central Station in 1903, and the 50 kW set from Wynberg was transferred there as well. (The British and South African Export Gazette, Sept 1901:123, Oct 1901:389, Mar 1902:669, Apr 1902:759; The Cape Argus (weekly edit) 1906-02-07; The Electrical Review, June 1906:903; Official South African Municipal Yearbook 1912: Table p340; Parsons RH, Development of the Parsons Steam Turbine, 1936:278)

The De Beers Consolidated Mines at Kimberley commissioned the first large turbo-generator of 1 MW capacity, in August 1903. A 200 kW set was installed at the Porges Randfontein Gold Mine and a 500 kW turbine at the Driehoek Power Station in 1904. The Rand Central Electric Works installed a 400 kW turbo-generator in 1905. Larger sets soon followed, including 6 MW sets installed by the Randfontein Estates Mines and 9,6 MW sets installed by the Victoria Falls and Transvaal Power Co at Rosherville and 11 MW sets at Simmerpan. (South African Mining Journal, Mar 1905:72; Report of the Power Companies Commission [T.G.13-’10] 1909:10; The Journal of the South African Institute of Engineers Vol. IX No 11 June 1911:274; Robertson GM, De Beers Central Power Station, in: The Journal of the South African Institution of Engineers Vol. X No 6 Jan 1912:130 and Vol. XII No 1 Aug 1913:1-25; Fenwick and Torr, Electric Power Supply to the Mining Industry in the Transvaal and Orange Free State, 1961:25; Troost and Norman, in: Transactions of the SA Institute of Electrical Engineers, Sep 1969:177).