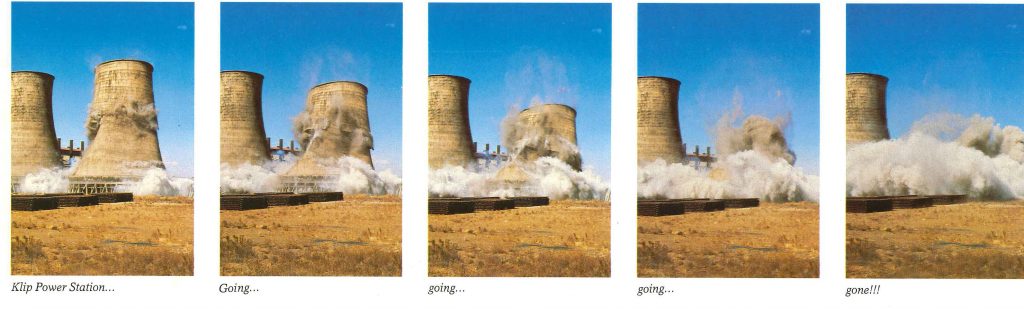

Klip Power Station

OVERVIEW

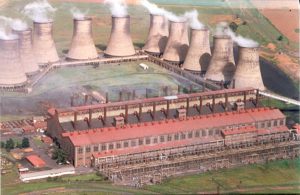

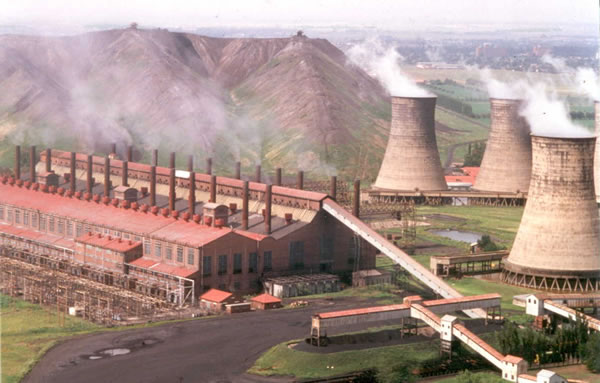

Klip Power Station was built as a result of the rapid growth in the demand for electricity that followed the increase in the price of gold in 1933. The first generator was started up in March 1936 and the last was taken into service in July 1940. With twelve 33 MW generators and four 7 MW house sets, giving a total of 424 MW of installed plant, Klip had the distinction of then being the largest steam power station in the Southern Hemisphere. As far as is known, it had the greatest output of any power station in the world at that time, and probably the lowest cost of production of any other similar station. The rate of construction and commissioning of plant constituted another world record. It was the first station in ESCOM to have cooling towers. [The name ESCOM was changed to Eskom in 1987]. The station was in operation for almost exactly fifty years, being closed down in March 1986. Total net electricity production amounted to slightly over one hundred thousand GWh (gigawatt-hours) or one hundred thousand million units.

The total coal consumption was 84,5 million metric tons. (ESCOM Annual Reports 1936:33, 1943:12, 1985:56 note 2) and Tables of Power Station Operating Statistics; Pickles & Trelease 1940:1; Eskom News Sep/Oct 1993:9)

When completed in 1940, the station capacity was over four times that of Witbank Power Station, previously the largest station owned by ESCOM. However, today it would need more than two-thirds the total capacity Klip had at completion to supply just the auxiliary requirements of a power station such as Majuba or Matimba.

BACKGROUND

With South Africa in the grip of the world-wide depression, at the end of 1932 the Government decided to abandon the gold standard. A sharp rise in the price of gold followed and the country began to experience rapid economic growth. The phenomenal increase in demand for electricity created by the expansion of the gold mining and other industries made it clear that an additional power station would be needed. (ESCOM Annual Report 1943:11)

The total installed capacity of the existing stations feeding into the Rand-Witbank area in 1932 was 360 MW, but it was not practical to extend these stations sufficiently to meet the expected growth in demand. Negotiations were started between ESCOM and the Victoria Falls and Transvaal Power Company (the VFP), with the object of producing power on the most economical basis in the interests of consumers as a whole. An agreement was entered into between the VFP and ESCOM by which a new station would be financed and owned by , but be constructed and operated by the VFP on behalf of . It was decided in 1933 to build Klip Power Station adjacent to the Klip River (=Stone River) at Redan, about 7 km north-east of Vereeniging. Like Vereeniging Power Station of the VFP, it would be a pithead station. It would be established adjacent to a new colliery shaft from which coal would be mechanically fed right into the bunkers. (Vereeniging Power Station had been the first in South Africa, and possibly in the world, to be sited on a coalfield). Preliminary plans were drawn up by the VFP, but their London engineers and ESCOM’s consultants, Merz and McLellan, collaborated on the final designs. (ESCOM Annual Reports 1933:5, 1943:11&12; Pickles & Trelease 1940:1; Troost and Norman 1969:178)

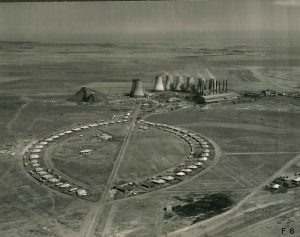

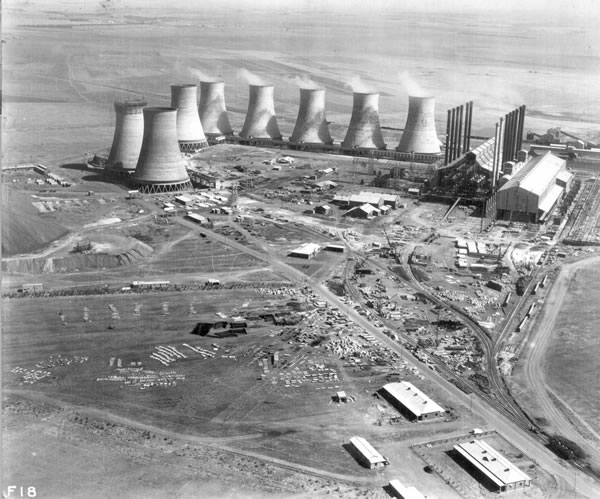

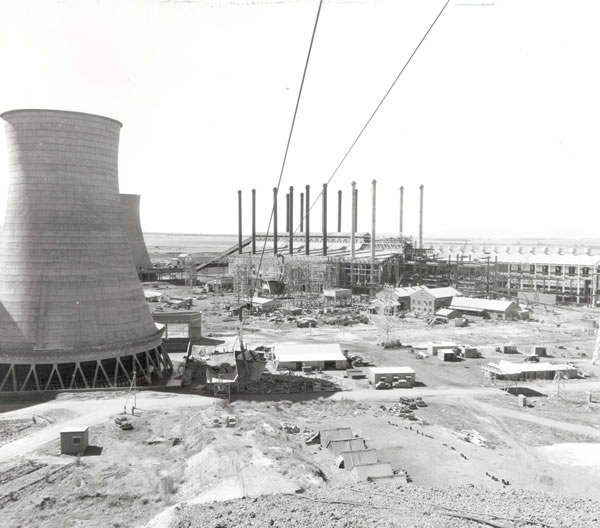

The power station under construction

CONSTRUCTION

A summary of the principal equipment installed is as follows:

| Year | Main Generators | House Sets | Boilers |

| 1936 | 4 | 8 | |

| 1937 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| 1938 | 2 | 1 | 6 |

| 1939 | 2 | 4 | |

| 1940 | 2 | 1 | ** |

| Total | 12 | 4 | **24 |

** The last two boilers were delayed by the outbreak of World War II (1939-1945), but were in service by 1943. However, as the boilers were interconnected and each could deliver an extra amount of steam, this did not materially affect the station output. An additional boiler of the same capacity was installed in 1958. (ESCOM Annual Reports 1935-1944, 1958:46; Conradie and Messerschmidt 2000:92)

The boilers were manufactured by Babcock and Wilcox, and were of the cross-drum marine type. They were fitted with chain grate stokers, airheaters, economisers, water tube furnace walls, superheaters, sootblowers and cyclone grit and dust collectors. Each unit was rated at 180 000 lb/h [22,7 kg/s] normal continuous rating. The steam pressure at the superheater outlet was 355 lb/sq.in. [2,55 MPa (abs)] at a temperature of 390/405 °C. Each boiler was provided with a separate steel chimney 8 feet [2,4 m] in diameter. These were originally 240 feet [73 m] high with the upper 100 feet [30 m] constructed of copper bearing alloy. The chimney height was later reduced to 56 m. To save costs, the chimneys were not free-standing but were tied to each other and anchored to the station buildings by means of steel stay-wires. Each bank of eight boilers was provided with a separate and independently operating ash handling system, and an ash disposal ropeway discharging onto an individual dump. The speed of the ropeway was 390 ft/min [2 m/s].

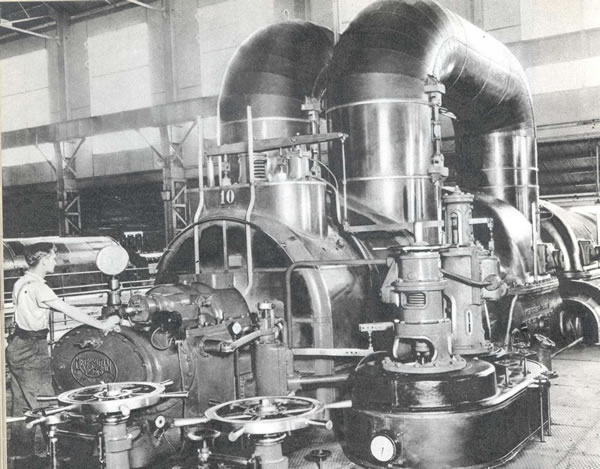

The 12 main turbo-generators were each of 33 MW economic and full load rating. These were the largest units, which at that time could be transported from the coast. There were also four 7 MW house sets. The steam pressure at the turbine stop valves was 350 lb/sq.in. [2,51 MPa (abs)] at a temperature of 390 °C. The main turbines were of the two cylinder double exhaust type manufactured by Metropolitan Vickers and the house sets were of single cylinder design. Two emergency steam driven feed pumps were installed.

Each generator transformer consisted of three single phase units of 13,333 MVA capacity. The voltage on the generator side was 10,5 kV (delta) and on the secondary side 88 kV (star). These transformers were water-cooled. The house sets were connected to the 2,1 kV station boards via 8,75 MVA reactors. Four station transformers of 8,5 MVA each were also provided to supply the 2,1 kV boards from the 88 kV bus-bars.

There were 10 cooling towers. The diameter at the base was 170 ft [52 m] and at the top 92 ft [28 m]. The height from the bottom of the ponds was 220,5 ft [67 m]. The weight of concrete in each tower was 2400 metric tons and the weight of steel reinforcing in each 360 metric tons. The quantity of water circulated in each tower was 1,98 million gallons per hour [2,5 kl/s]. The designed inlet and outlet temperatures of the water were 38 °C and 28 °C with an atmospheric temperature of 21 °C and humidity of 75%. The actual average operating temperatures in 1940 were 30,4 °C and 22 °C respectively. Make-up water was taken from the Vaal Bank Dam and pumped from the Vereeniging pumping station. The average water usage of the station was 5,7 l/kWh sent out.

Capital expenditure during construction amounted to approximately £6,3 million. A breakdown of these costs is given below (excluding Land and Rights £ 129 993)

| Buildings (power station) | £ 610 988 |

| Boilers and ash plant | £ 2 407 133 |

| Turbines and generators | £ 1 196 734 |

| Switchgear, transformers and cables | £ 558 314 |

| Pipework | £ 328 705 |

| Cooling towers, ponds and ducts | £ 669 637 |

| Coal plant | £ 186 180 |

| Railways, roads, miscellaneous | £ 316 936 |

| TOTAL | £ 6 274 627 |

(Information and data source for technical details from: Andrews 1937:22-24;

Kanthack 1938:2-9; Pickles and Trelease 1940; ESCOM Annual Report 1940:21;

ESCOM Twenty-five Years 1923-1948:45)

OPERATION AND PRODUCTION

From 1940 to 1961 the station net production averaged approximately 2 500 GWh per year. For the next 22 years, as the operating function of the station changed from base-loading to peak-loading, production dropped fairly steadily to about 1 300 GWh per annum. However, maximum net power remained consistently close to the full sent-out rating of 394 MW until 1977. During the closing years, 1984-1986, production was much reduced.

| Year | Net Generation GWh | Net Max Power MW | Load Factor (net basis) % | Thermal Efficiency net basis % | Coal Consumed metric ton | Calorific Value of Coal MJ/kg | Cost of Coal R/metric ton |

| 1937 | 1 350 | 219 | 85,1 | 21,4 | 996 267 | 22,42 | 0,33 |

| 1941 | 2 676 | 375 | 81,4 | 21,8 | 2 010 333 | 21,98 | 0,39 |

| 1952 | 2 763 | 375 | 82,5 | 20,3 | 2 238 718 | 21,06 | 1,07 |

| 1961 | 2 480 | 392 | 72,2 | 20,3 | 1 854 799 | 23,70 | 2,36 |

| 1967 | 2 059 | 399 | 58,9 | 20,1 | 1 695 542 | 21,12 | 2,91 |

| 1977 | 1 447 | 378 | 43,7 | 18,2 | 1 380 840 | 20.74 | Not available |

| 1983 | 1 335 | 301 | 46,9 | 17,5 | 1 499 626 | 18,35 | Not available |

| 1985 | 348 | 225 | 17,7 | 14,9 | 469 706 | 20,39 | Not available |

COAL SUPPLIES

A mining disaster occurred in the Northern Free State at the Coalbrook coal mine on 21 January 1960. This had a major impact on ESCOM’s power stations and a temporary reduction in electricity supply in the Rand-Witbank area became unavoidable from 13 to 19 March 1960. Emergency measures were introduced to bring coal by rail and by road to the power stations immediately affected. Coal from Cornelia colliery was railed to Taaibos Power Station, as Witbank coal proved unsuitable there. Witbank coal was used at Klip and Vereeniging. Over this period coal received at Klip had a calorific value over 10 200 Btu/lb [23,7 MJ/kg]. This was the highest during the operating life of Klip. The lowest calorific value received was 18,35 MJ/kg, in the year 1983. (ESCOM Annual Report 1959:9; ESCOM Annual Reports-Tables of Power Station Operating Statistics)

ASH DISPOSAL

THE KLIP TRAINING CENTRE

CLOSURE AND DEMOLITION

ESCOM’s General Manager, Ian McRae also knew her well. He had worked for her for six months and entertains the rest of the guest with incidents from the good old days. Then finally, it was the time to say goodbye. The VIP guests moved to the power station where they assembled at turbine five. It was the turbine which Lionel Oëhley started up 50 years ago. Today it was his privilege to switch it off. The engine room was fitted with a high pitched whistling sound. The turbine operated at 3 000 revolutions per minute. In the control room Ian McRae and Ray Chapman were ready to bring it to a standstill for the last time.

The revolutions slowly dropped. The old lady was losing her strength, she lets off her last steam, while Lionel Oëhley assisted by Japie Brits, Herman van Rooyen, Chris van Oordt and Konnie Verwey turn off the steam valves. Some of the guests gave the turbine a last loving stroke before they walked away. At the entrance they looked back. Her vast engine hall is quite, but the turbine was still shimmering in the daylight.

It took 25 months to build Klip power station. Plans for the building were approved in 1933 between the commission and their engineers in London, with the co-operation of the consultants Merz and McLean

Excavations began in the first week of June 1934 and 21 months later, on 10 March 1936, the first 33 000 kW engine and two boilers were put into operation. During the following four months the rest of the sets, with boilers of the same size, started generating power.

In 1940 Klip was the biggest coal driven power station in the southern hemisphere with possible the biggest delivery capacity by any coal driven station in the world. The low cost of developing power has never been equaled by a similar station. In 1953 the Springfield coal mine, which served as a source for Klip, was exhausted. Since then approximately 5 000 metric tons of coal had to be transported daily to the power station over a distance of 100 km.

Explosives demolished the cooling towers during 1987. These were the first cooling towers to be built at an ESCOM power station and the first to be demolished. The power station plant and equipment was disposed of as scrap, the buildings were totally demolished and the land rehabilitated. Only the workshops and township remain. In 2004, the land was still owned by Eskom. (ESCOM News No.80 June 1987; Simunye Power Stations)

When the staff housing became redundant after closure of the power station, rather than demolish the buildings, which were fundamentally still sound, Eskom decided to put them to good use and improve the lot of its pensioners at the same time. As the township was not a proclaimed municipality or suburb, the houses could not be sold. The estate included 129 houses and single quarters for 73 employees, as well as other facilities. The township was transformed into a proper retirement village with facilities for local management, medical care, catering and recreation. It was well sited near to Vereeniging and the Reef, where tenants could enjoy the benefits of the city together with the peace and the amenities of the Vaal River.

Accommodation was to be administered jointly by the tenants and the Eskom Foundation, an organisation formed specifically to provide housing and related facilities for Eskom pensioners. Mr Lood Rothman, Eskom’s Senior General Manager, handed over the housing estate for development as a retirement village at a handing-over ceremony in June 1988. At the ceremony, Mr Louis Roberts showed off the gardening trophy that had been won by Klip. In later years the Eskom Foundation withdrew participation, and the staff of Lethabo Power Station managed the township. (Eskom News No.107/July 1988:3)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Andrews WO: Notes on a performance trial of a boiler at Klip Power Station. In: The Journal of the South African Institution of Engineers, September 1937

- Conradie SR and Messerschmidt LJM: A Symphony of Power – The Eskom Story – Chris van Rensburg Publications (Pty) Ltd, Johannesburg, 2000

- Electricity Supply Commission: Annual Reports,1948-1984

- ESCOM Brochure – Klip, Vaal & Vierfontein Power Stations

- ESCOM: Golden Jubilee 1923-1973

- ESCOM: Megawatt 1966-1982

- ESCOM News / Eskom News 1982-1993

- ESCOM/Eskom: Statistical Yearbooks, 1985-1990

- Kanthack FE: Inaugural Address. In: Journal of the South African Institution of Engineers, August 1938

- Pickles V and Trelease JS: Klip Generating Station – A General Description. In: The Transactions of the South African Institute of Electrical Engineers, May 1940

- Troost Dr N and Norman HB: Electricity Supply in South Africa 1909-1969. In: The Transactions of the South African Institute of Electrical Engineers, September 1969