Vaal Power Station

OVERVIEW

Vaal Power Station commenced operation in January 1945 with an installed plant capacity of 66 MW. It was the first ESCOM station to be built in the Orange Free State [The name ESCOM was changed to Eskom in 1987 and the Orange Free State is now known as the Free State]. The power station was well placed to supply the initial requirements of the new gold deposits discovered in the Free State in 1938. The station had been planned to have 108 MW of generating plant installed initially, scheduled to be in operation in 1941, and to be extended later to 400 MW, if necessary. However, delivery of equipment was delayed and the construction programme seriously retarded by difficulties arising out of World War II (1939-1945). When finally completed in 1953, Vaal had 318MW of generating plant installed. (ESCOM Annual Reports 1938:45, 1943:12, 1945:45, 1953:89; ESCOM Twenty-five Years 1923-1948:28)

Vaal Power Station was in operation for almost 45 years. It was decommissioned during 1989, having reached the end of its economic life. Total net electricity production amounted to 69 thousand GWh (gigawatt-hours) or sixty-nine thousand million units. The total coal consumption was 62 million metric tons. (ESCOM Annual Report 1989:24 and Tables of Power Station Operating Statistics)

BACKGROUND

The increase in the price of gold in 1933, after South Africa abandoned the gold standard, led to rapid economic growth. Establishment of the South African Iron and Steel Corporation (Iscor) in 1928, also resulted in an increase in steel-related manufacturing industries. Even the large power resources of the Klip Power Station, started up in March 1936, were not expected to keep pace with the ever-increasing demand for electricity. In co-operation with the Victoria Falls and Transvaal Power Company (the VFP), ESCOM therefore decided in 1938, to build the Vaal Power Station. It was to be constructed on the Free State side of the Vaal River and would be the first ESCOM station to be built in the Free State. As in the case of Witbank and Klip, the station would be financed and owned by ESCOM, but be constructed and operated by the VFP on behalf of ESCOM. Like Klip, it was also a pit-head station. The site chosen was on a coalfield that was opened up and developed to supply the fuel requirements of the station. (ESCOM Annual Report 1943:12)

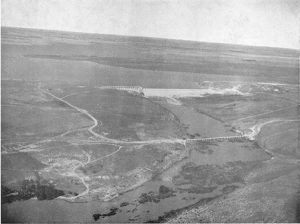

By contributing £124 875 towards the cost of the Vaalbank Dam, ESCOM obtained the right to draw 18,5 million gallons of water per day [84 megalitres per day] from the Vaal River, thus securing an adequate supply of cooling water for both Klip and Vaal Power Stations. (ESCOM Annual Report 1943:12)

The site was on the farm “Bankfontein”, 9 km SSE of Vereeniging, at Viljoensdrif in the Heilbron district of the Free State, at an altitude of 1486 metres above sea level. A plentiful supply of coal was available on that and adjoining farms. New gold deposits were first located in the northern Free State in 1938, and later richer deposits further south near the town Odendaalsrus.

Vaal would be strategically placed to supply the electricity requirements of these new goldfields. The nearest mining development taking place was about 190 km from the power station, and it was proposed to transmit the power via 88 kV overhead lines. Approximately 291 hectare of land was purchased including 68 ha purchased in 1940 to provide for more ash dumps and power line networks. Construction at site had been inaugurated by ESCOM’s Chairman, Dr HJ van der Bijl, at a ceremony held on 23 March 1939, just over five months before World War II (1939-1945) broke out. The original plant was expected to be in operation by 1941, but when delays in delivery of the plant due to the war conditions became apparent, it was hoped that the station would be in partial operation towards the end of 1943. (ESCOM Annual Reports 1938:45, 1940:22, 1942:6)

Orders for three 33 MW turbo-alternators and a 7 MW house set were placed with the manufacturers in Sweden in September 1939, the month in which war was declared. Although manufacture of the plant was completed, the war prevented these sets from being delivered until after hostilities ended. However, in spite of the slowing down of mining operations during the war making the need for Vaal not quite as urgent, two 33 MW sets were nevertheless ordered from Great Britain in 1940. (ESCOM Annual Report 1943:12, 1945:45)

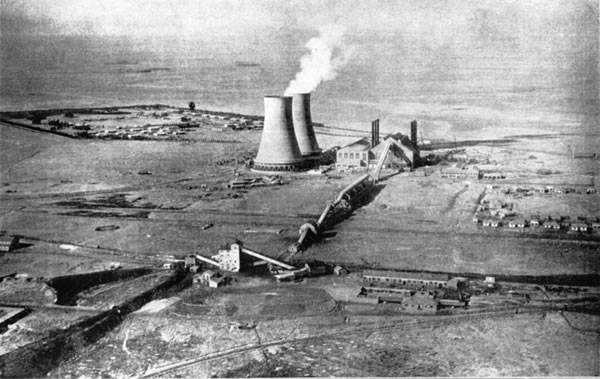

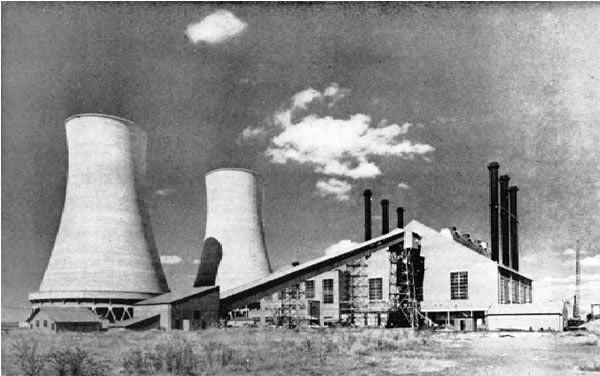

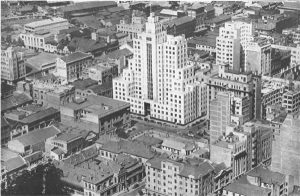

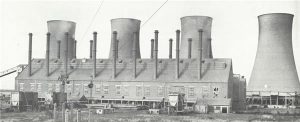

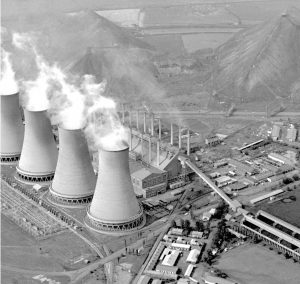

Construction

By 1940 erection of the steel-framed generator house was in progress and two of the cooling towers were completed. These were the tallest structures in South Africa at the time, 320 feet [97,5m] in height. The internal diameter at the bottom was 205 feet [62,5m] and at the top 120 feet [36,5m]. Almost the entire ESCOM House in Johannesburg, the new 21-storey head office opened by the Prime Minister in 1937, could be placed inside the tower with 25m to spare at the top. The quantity of water circulated in each tower was 4,0 million gallons per hour [5,05kl/s], twice as much as that in the towers at Klip. The designed inlet and outlet temperatures of the water were 36°C and 27,5°C with an atmospheric temperature of 21°C and humidity of 75%. Make-up water was taken from a pumping station below the Vaalbank Dam via a pipeline about 6km in length. (ESCOM Annual Report 1940:22, 1944:46, ESCOM Twenty-five Years 1923-1948:28&46)

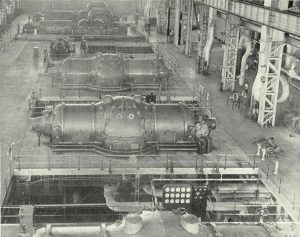

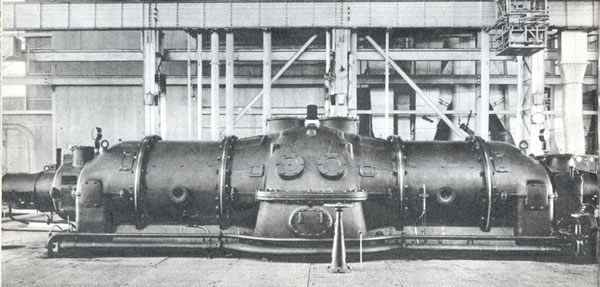

The three main turbo-alternators and the house sets ordered from the Swedish firm ASEA were Ljungström sets (pr. yung-strauom (Swed)=heather river). These were radial flow reaction turbines, invented by Birger Ljungström (1872-1948) and patented under British Patent 7833:1907. Frederik Ljungström and others further developed the design. The steam flow was outwards from the shaft, with blades mounted on two wheels rotating in opposite directions. There were no fixed blades. Each wheel was coupled to an alternator that carried half the load. An outstanding feature was the extreme compactness of the design.

The Ljungström turbine was manufactured under licence by Svenksa Turbinfabriks Aktiebolaget Ljungström (STAL) in Sweden, and Brush Electrical Engineering Co in England. Sets as large as 65 MW were installed in Sweden in 1949. The Vaal radial flow sets were at that time unique to ESCOM, although there were municipalities in South Africa with smaller sets in operation. When ESCOM took over the West BankI Power Station at East London in 1947, all sets at that station were Brush Ljungström sets and ESCOM added another 7,5 MW set. Two Brush Ljungström 1,5 MW sets were also in operation at King William’s Town Power Station when taken over by ESCOM in 1948. (ESCOM Twenty-five Years 1923-1948:46&48; Ljungström 1949:211-218; Auger 1965:65; ESCOM Megawatt No.30/1974:12; A History of Technology 1978, Vol VII:1030; Hanks & Hodges 1988:330; McGraw-Hill Dictionary of Engineering 1997:301)

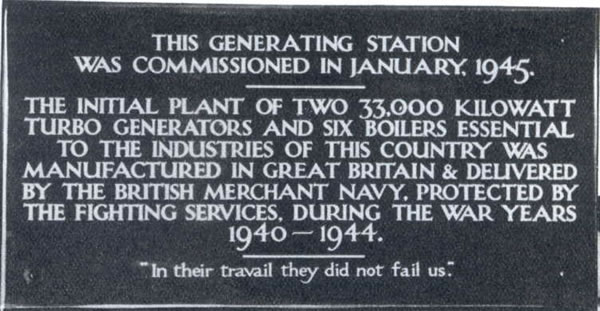

Due to the German invasion of Denmark and Norway during the war, it became impossible to ship the sets from Sweden, even though manufacture had been completed. Two 33 MW sets, of the normal axial flow type, were therefore ordered from Metropolitan Vickers in Great Britain in 1940. They were safely delivered by the British Merchant Navy, protected by the Fighting Services, despite the threat from enemy submarines. A commemoration plaque to this effect was mounted in the main entrance hall of the power station. A 40 MW set for Congella Power Station at Durban, the largest set at that time ordered by ESCOM, was lost at sea in 1943 when the ship delivering it was sunk by enemy action. Altogether 252 Allied merchant ships were sunk in the south Atlantic and Cape waters during the war. (ESCOM Annual Reports 1943:17, 1944:46, 1945:45; Knox-Johnston 1989:82)

The first of the two Metropolitan Vickers 33 MW sets went into service on 22 January 1945 and the second in April 1945. The first two of the three 33 MW Ljungström sets and the 7 MW house set ordered from ASEA in 1939 were delivered in October 1945, soon after war hostilities had ended. The house set was started up on 10 April 1946 and the two main sets were completed on 1 July and 5 November 1946 respectively. The last ASEA set was delivered in 1946 and commissioned in March 1947. By the end of 1947 the station-installed capacity was 172 MW and extensions comprising four additional 33 MW sets, two house sets, twelve boilers and two cooling towers were on order. (ESCOM Annual Reports 1945:45, 1946:47, 1947:48)

The second 7 MW house set was in service at the end of February 1950 and Generator 6 was on load on 15 February 1951. Special measures were adopted to enable Generator 7 to be placed in service in 1951, but the full output of the seven generators then installed would not be attained until boilers 11-14 were in service. By the end of 1952, eight main generators, two house sets and twelve boilers were in commercial service. At the end of 1953 there were nine main generators, three house sets, seventeen boilers and four cooling towers in commercial service. The last boiler was commissioned in 1954 making an ultimate installed plant capacity of 318 MW. (ESCOM Annual Reports 1949:52, 1950:46, 1951:89, 1952:89, 1953:89, 1954:91)

A summary of the principal equipment installed is as follows. (Data from ESCOM Annual Reports)

| Year | Main Generators | House Sets | Boilers |

| 1945 | 2 (axial flow) | 6 | |

| 1946 | 2 (radial flow) | 1 (radial flow) | |

| 1947 | 1 (radial flow ) | ||

| 1948 | |||

| 1949 | 3 | ||

| 1950 | 1 (radial flow) | 1 | |

| 1951 | 1 (axial flow) | ||

| 1952 | 2 (axial flow) | 2 | |

| 1953 | 1 (axial flow) | 1 (radial flow) | 5 |

| 1954 | 1 | ||

| TOTAL | 9 | 3 | 18 |

Babcock and Wilcox manufactured the boiler plant. There were 18 units, all fitted with chain grate stokers. These were the largest link-type stokers in the world. Each unit was rated at 190 000 lb/h [23,9 kg/s] normal continuous rating. Each boiler was provided with a separate steel chimney lined with concrete. The chimney diameter was 8,5 feet [2,6 m] and the height 200 feet [61 m]. The chimneys were anchored to the building structure by means of steel wire stays. The steam pressure at the boiler superheater outlet was 360 lb/sq.in. [2,59 MPa (abs)] at a temperature of at 810 °F [432 °C]. The steam conditions at the turbine inlets were 350 lb/sq.in. [2,5 MPa (abs)] and 800 °F [427 °C]. (Escom Twenty-five Years 1923-1948:46; ESCOM Golden Jubilee 1923-1973:53; ESCOM Annual Report 1980:49; ESCOM Brochure – Klip, Vaal & Vierfontein Power Stations)

Each generator transformer consisted of three single phase units of 13,333 MVA capacity. The voltage on the generator side was 10,5 kV and on the secondary side 88 kV. The house sets generated at 3,3 kV. There were three station transformers each of 8,5 MVA with voltage ratio of 88/3,3 kV. (ESCOM Twenty-five Years 1923-1948:33; ESCOM Brochure – Klip, Vaal & Vierfontein Power Stations)

| Land and rights | £ 5 347 |

| Buildings and civil works | £ 2 357 400 |

| Machinery and plant | £ 8 517 009 |

| TOTAL | £ 10 879 756 |

Operation and Production

For the first 10 years of its operating life, net electricity production at Vaal increased steadily to a maximum of 2 195 GWh in the year 1954. For the next 29 years net production averaged about 1 850 GWh. For the closing 6 years production dropped steadily, and in the final year 1989, auxiliary consumption exceeded generation. Auxiliary consumption in the station averaged approximately 6% of generation, varying from about 5,5% to 7,5% depending on load factor. Maximum net power remained consistently close to the sent out rating of 295 MW for the years 1953 to 1983, reducing during the closing years. (See production chart)

Maximum net annual production was 2 195 GWh, sent out in the year 1954. Maximum thermal efficiency was 22,9% and was achieved also in the year 1954. Maximum net power was 301 MW, produced in the year 1955. Statistics for these years, as well as the first and last full years of production, are given in the table below.

| Year | Net Generation GWh | Net Max Power MW | Load Factor (net basis) % | Thermal Efficiency net basis % | Coal Consumed metric ton | Calorific Value of Coal MJ/kg | Cost of Coal R/metric ton |

| 1946 | 582 | 104 | 63,9 | 22,5 | 430 839 | 21,66 | 0,66 |

| 1954 | 2 195 | 291 | 86,0 | 22,9 | 1 651 345 | 20,89 | 0,75 |

| 1955 | 2 106 | 301 | 79,8 | 22,8 | 1 586 201 | 20,96 | 0,79 |

| 1965 | 2 066 | 291 | 81,0 | 20,9 | 1 799 770 | 19,77 | 1,15 |

| 1975 | 1 793 | 289 | 70,8 | 19,8 | 1 712 010 | 19,08 | 3,22 |

| 1985 | 1 107 | 236 | 46,8 | 17,3 | 1 305 472 | 17,64 | Not available |

| 1988 | 36 | 92 | 1,7 | 11,2 | 64 994 | 17,46 | Not available |

MAJOR BREAKDOWNS

A breakdown of a generator occurred at the beginning of December 1955. As a precautionary measure the two further machines of the same design were taken out of service. The cause of the failure was investigated with assistance of the manufacturers, and it was expected to return the units to service by the winter. Modifications were made to the three sets and they were returned to service between July and October 1956. The loss of plant was reflected as a substantial reduction in the station output for 1956 (see production chart). The loss had to be made up by increasing loading at the other stations in the pool and in addition power purchases had to be made from the Municipalities of Johannesburg and Pretoria. (ESCOM Annual Reports 1955:54, 1956:51)

COAL SUPPLIES

The coal used was run-of-mine washed and crushed to minus 3/4 inch [19 mm] and received by conveyor belt straight from the pithead of the new Cornelia South Colliery. The calorific value was over 21 MJ/kg for the first 8 years, dropping to below 20 MJ/kg by 1960, below 19 MJ/kg by 1973 and below 18 MJ/kg in 1985. The station was not adversely affected by the Coalbrook mining disaster in 1960. The Cornelia Colliery, belonging to the Anglo-American Corporation, was later extended and re-named New Vaal Colliery to supply Lethabo Power Station as an open-cast mine with coal as low as 15 MJ/kg in calorific value. Lethabo was built 3½ km northeast of Vaal Power Station and the first set there was commissioned in December 1985. (ESCOM Twenty-five Years 1923-1948:46; ESCOM Annual Reports-Tables of Power Station Operating Statistics; Escom Megawatt No.65/April 1981:6; Eskom News July 2003:32)

ASH DISPOSAL

The ash handling plant comprised a system of high velocity water sluiceways, ash and water sumps, telpher grabs and ash bins. From these bins the ash was transferred into the buckets of the aerial ropeways for conveyance to the dumps. The total amount of coal consumed over the 44-year life span of the station amounted to 62 million metric tons. With an ash content of approximately 25%, the ash dumps grew to a considerable size. After closure of the station the ash dumps were taken over by Roshcon, a division of Eskom Enterprises. The ash is to be used for the making of building bricks. (Simunye Decommissioning 2004)

STAFF

In 1945, negotiations started that lead to the expropriation of the VFP and the purchase by ESCOM of its assets. This took place on 1 July 1948. Vaal Power Station had always been owned by Escom, but had been operated by the VFP on behalf of ESCOM. The VFP staff members were transferred to its subsidiary, the Rand Mines Power Supply Company, up to 31 December 1948. From 1 January 1949 they were formally transferred to ESCOM. During the early 1980’s the staff complement consisted of 858 employees. At closure of the power station in 1989, the staff members were either transferred to other stations or took retirement. (ESCOM Golden Jubilee 1923-1973:21; ESCOM Brochure – Klip, Vaal & Vierfontein Power Stations)

CLOSURE AND DEMOLITION

During the 1980’s Eskom had been commissioning its new giant six-pack power stations. But due to a decrease in the rate of growth in the demand for electricity, Eskom began to experience a surplus of generation capacity. The older and less efficient stations were thus no longer required. Vaal Power Station was closed down in 1989, having reached the end of its economic life. (ESCOM Annual Report 1989:24; Conradie and Messerschmidt 2000:259-260)

An agreement was concluded with United Carbon Producers (Pty) Ltd in August 1990 whereby United Carbons would utilise certain facilities at the power station for the purpose of producing smoke-less fuels for domestic use and char for industrial use. The boilers would be modified for use as furnaces. Certain other plant and equipment, buildings, housing and adjacent land were to be leased for a period of 15 years. (Eskom News No.154/16 Oct 1990:3

The four cooling towers were demolished in July 1996 by means of explosives. These were the tallest structures in South Africa when they were built, but were sadly reduced to rubble within seconds when they were demolished. (Eskom News August 1996:3)

The smoke-less fuel project was not a financial success. After 1998 the plant was sold as scrap, the power station buildings totally demolished, and the land rehabilitated. The township has now been taken over and is being administered by the staff at Lethabo Power Station. The pumping station at the Vaal River has also been taken over by Lethabo. (Simunye Decommissioning 2004)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- A History of Technology (Edited by Trevor L Williams) Volume VII – Clarendon Press – Oxford, 1978

- Auger, CP – Engineering Eponyms – The Library Association – Staples Printers Ltd, Kent, England, 1965

- Conradie SR and Messerschmidt LJM: A Symphony of Power – The Eskom Story – Chris van Rensburg Publications (Pty) Ltd, Johannesburg, 2000

- de Villiers I: The development of the Electricity Supply Commission in the post-war years. In: The Transactions of the South African Institute of Electrical Engineers, February 1957 (Presidential Address)

- Electricity Supply Commission: Annual Reports, 1948-1984

- ESCOM Brochure – Klip, Vaal & Vierfontein Power Stations (approx 1981)

- ESCOM: Golden Jubilee 1923-1973

- ESCOM: Megawatt 1966-1981

- ESCOM News / Eskom News

- Eskom: Statistical Yearbooks, 1985-1990

- Hanks P & Hodges F: A Dictionary of Surnames – Oxford University Press, 1988

- Knox-Johnston R: The Cape of Good Hope – A Maritime History – Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1989

- Ljungström Dr F: The Development of the Ljungström Steam Turbine and Air Preheater. In: Institution of Mechanical Engineers (London), Proceedings, Vol 160, September 1949 (pages 211-223)

- McGraw-Hill Dictionary of Engineering, Fifth Edition – New York, 1997

- Reay Dr DB: Some mechanical advances in the power station practice of the Electricity Supply Commission. In: The Certificated Engineer, June 1961

- The South African Engineer and Electrical Review – February 1945

- Troost Dr N and Norman HB: Electricity Supply in South Africa. In: The Transactions of the South African Institute of Electrical Engineers, September 1969