Umgeni Power Station

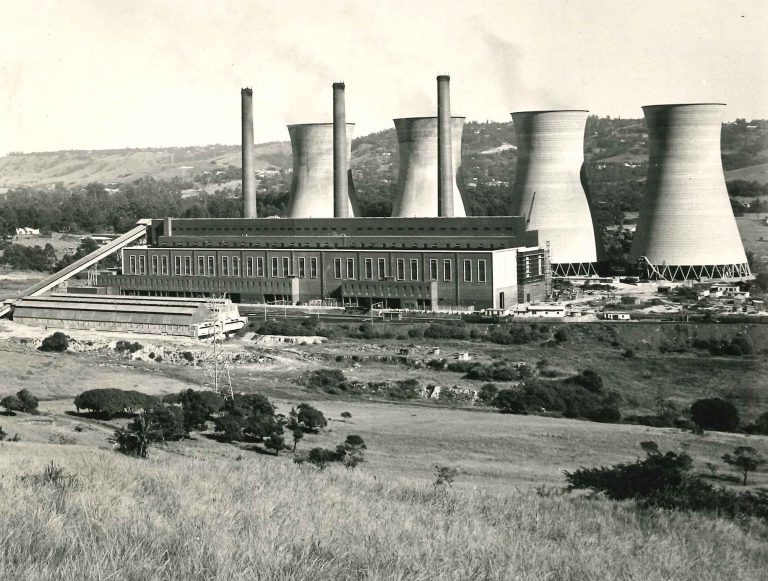

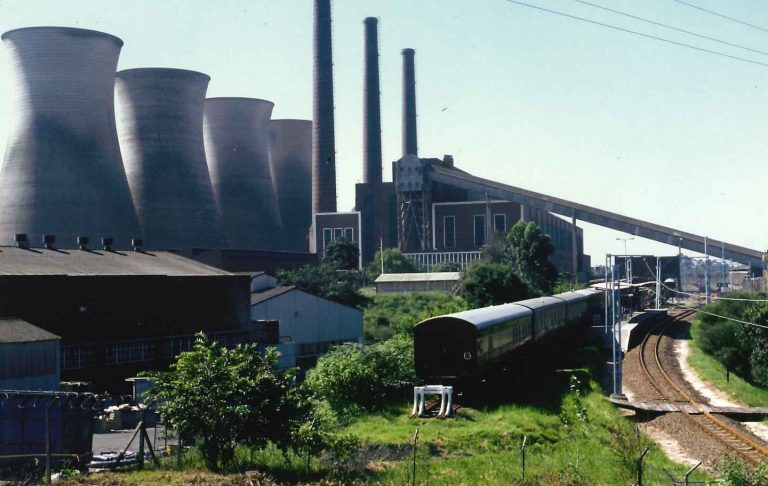

By the time the Umgeni Power Station was officially decommissioned in February 1989, it had operated for 35 years and was regarded by ESCOM as one of its ‘grand dames’ of yesteryear. Its four cooling towers had become a landmark and symbol of industrial expansion in the Pinetown/New Germany area in Natal (now known as KwaZulu-Natal). Indeed, the area and particularly New Germany owes its growth to the establishment of the power station.

The Umgeni Power Station was located to the east of the point where Richmond and Van der Bijl roads meet in New Germany. Today as one drives through the area where the power station was situated, there is no indication that such a structure had existed there, except for ESCOM Road west of the site and the Umgeni sub-station. Gone are the cooling towers, the chimneys, the turbines and boilers that provided the power for KwaZulu-Natal’s industry and homes.

THE ESTABLISHMENT

The immediate post-Second World War period in South Africa saw the country’s economy expanding rapidly. Sectors such as manufacturing and commerce in particular began to boom. In the thirty years between 1946 and 1975, economic growth averaged over 7% annually. The heavier industries producing metals, machinery and chemicals also expanded as South Africa became part of the post-Second World War globalisation of multinational investment. By 1948, the demand for electricity had expanded from all classes of consumers: mining, industrial, traction, domestic and rural. A new programme of power station construction was required. In Durban, power was required for the electrification of the rail system and to meet the demand from the municipality, local industry and other consumers. Natal’s two power stations Congella and Colenso had been built in the 1920s and were no longer able to cope with the increasing demand in spite of post-war extensions.

Consequently, in 1947, it was decided to build a power station west of Durban, in the area of New Germany. New Germany was close to the main communication axis and in close proximity to the Umgeni River. The decision to build the new power station here was of great significance for the New Germany community. Up to 1948, the area had essentially been a farming community, indeed it did not have its own supply of electricity until that year. However, the establishment of the power station initiated a period of industrial growth that developed New Germany into what it is today.

The development of the power station site required New Germany to have some form of local government with which ESCOM could negotiate. A road servitude had to be acquired from local farmers and various contractors employed thousands of labourers who required sanitation, water and housing. Moreover, before major construction of the power station could commence, a tar road was required to carry materials and heavy equipment to the site.

The result was that a group of prominent New Germany personalities including HW (Otto) Volek established a Health Committee. One of the Health Committee’s first acts was to request ESCOM to submit plans of its proposed road system in order to come to an arrangement about distribution of costs. In addition, in early 1948, a Planning and Zoning sub-Committee was formed to investigate zoning around the power station area.

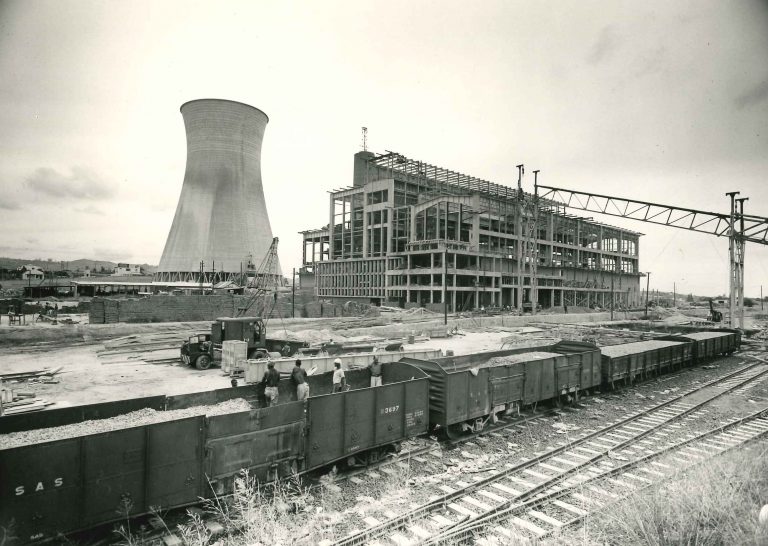

By September 1949, ESCOM had begun building the power station and with this, property values in New Germany increased. Work had begun on the 3½ kilometre railway line from Sarnia, south of the power station site. ESCOM intended the initial installation to be four 180 000 pounds per hour boilers and two 30 MW turbo-generators. The anticipated cost was £4 750 000. Much of the boiler contract was to be carried out in South Africa.

Within a year, some 40 hectares of land had been purchased and a large number of servitudes arranged for transmission lines and railway sidings. The site was being levelled, a tar road added (this was later taken over by the New Germany Health Committee) and the railway line and its siding were nearing completion. By the end of 1951, the foundations of the turbine house and the boiler house were almost complete, as well as the sub-foundations of turbo-generators. Work had also begun on Springfield substation that would be the endpoint for the 132 kV line between Colenso, Umgeni and Congella power stations.

This large-scale development meant that the Health Committee felt that it lacked the necessary authority to negotiate with ESCOM. In August 1951, the area was elevated to the status of a town board and the Administrator of Natal’s permission was requested to allow the area to be properly planned. Areas were laid out with provision for industrial development around the power station. When the Town Board sought borough status in order to expand its authority,ESCOM officials supported this move.

Despite this progress, the construction of the station was slowed by delays in manufacturing and delivery of material to the site. Consequently, the Natal Undertaking Manager, Mr. EL Damant reported that the power station could only be commissioned in February or March 1954.

During 1952 and 1953, the erection of the first two boilers and generators had begun and two 132 kV transmission lines were under construction, one from Colenso power station to Umgeni power station (183 route kilometres). Another went from Umgeni to the now completed Springfield substation (13 route kilometres). Companies such as Dorman Long, which was involved in the fabrication and erection of Umgeni’s steel structure, worked feverishly to meet the date of commissioning. Meanwhile all senior staff appointments at Umgeni had been finalised and arrangements made for the majority of the operating staff to be drawn from Colenso and Congella power stations.

Umgeni’s planning and construction took shape under three ESCOM chairmen, its founding chairman Dr HJ van der Bijl and his successor Mr AM Jacobs, who was succeeded by Dr JT Hattingh. The 400 kV grid was introduced during the chairmanship of Dr RL Straszacker. The final downscaling began with Mr Jan H Smith as chairman and actual closure with Dr JB Maree as chairman.

IN OPERATION

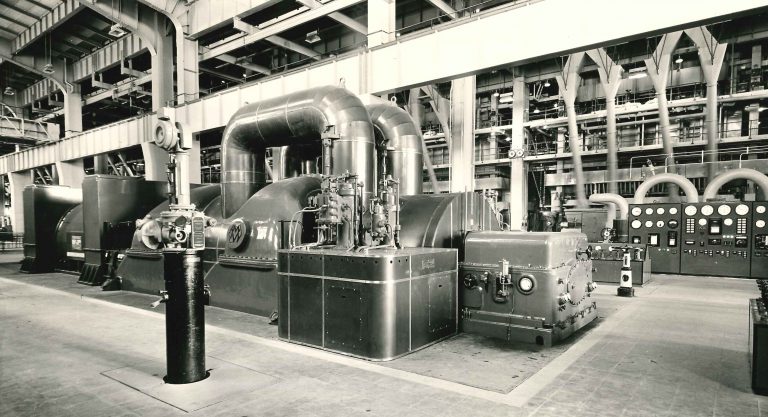

The first generator and two boilers were ready for running tests in April 1954. Generation was commenced at Umgeni on 2 April 1954. By May, it was supplying the Durban Corporation with 33 kV and by August, a third boiler had been added. The change rooms, mess, recreation rooms and stores were still being constructed.

ESCOM’s capital costs increased substantially in the Southern Natal region due to the construction of the Umgeni Power Station. Durban Undertaking’s schedule of expenditure on its Capital Account as at 31 December 1954 was as follows:

| Year ending 31 Dec ’53 | Year ending 31 Dec ’54 | Total at 31 Dec ’54 | |

| Land and rights | £131 206 | £10 316 | £141 522 |

| Building and Civil works | £3 051 753 | £311 431 | £3 363 184 |

| Machinery and Plant | £7 969 217 | £1 353 292 | £9 322 509 |

| £11 152 176 | £1 675 039 | £12 827 215 |

In 1955, No. 4 boiler and a second 30 MW turbo-generator were commissioned. Output increased to 228 million units and in order to facilitate interconnection between Umgeni and Congella, a substation was being built at Coedmore, south-east of Umgeni. Meanwhile, ‘teething’ troubles with the new plant were in the process of being rectified. Problems had been encountered on the boilers with air-heater operations and dust collectors were being studied. A second cooling tower was completed in 1957. An architect employed by Merz and McLellan, the consulting engineering firm, jokingly referred to the cooling towers as fertility symbols. He went on to father several children. The builders named all of the towers after those four children. Generator 3 and boilers 5 and 6 were commissioned in 1957. Generator 4 and boilers 7 and 8 were commissioned in 1958.

By 1961, output from Umgeni continued to increase. Boilers nos. 9 to 13 had been put into operation. The first of two 60 MW turbo-generators was placed on load at end of February 1961, and the second in November 1961. Extension ‘B’ to Umgeni (the two 60 MW sets and five boilers) increased the station output to over 1 000 million units in 1962. As a result of the Coedmore substation, pooling of Congella, Umgeni and Colenso was much improved. A newspaper article written at this time notes that this extension was necessary due to Natal’ s demand for power. It was the second time that Umgeni’s output had doubled. The station had originally been built around the two 30 MW generating sets but now output was being increased to 240 MW.

The article observed that although some residents in the suburb of Kloof complained about the unsightliness of the power station, it was the pride of ESCOM and was considered the cleanest and easiest of stations to run. At this time, its 13 boilers consumed about 2500 tons of coal a day, emitting the minimum of smoke. This was due to the firing system, which used a moving grate with a bed of coal, instead of burning pulverised coal (like Congella power station). Its output radiated along four main channels:

- To the immediate area, where electricity was retailed by the Durban Corporation. As it was, local industry via the Durban Corporation was one of the main users of its power.

- To the Springfield sub-station for supply to the main Durban Corporation, and on to the Natal north coast.

- To Mason’s Mill in Pietermaritzburg with coupling to Colenso.

By 1963, ESCOM had arranged for the distribution of electrical power from Umgeni to areas previously supplied by the privately-owned Empangeni and Eshowe power stations. Umgeni Power Station’s statistics for that year indicated the following:

| Station | Units generated GWh | Units sent out GWh | Peak MW Max demand | Station load factor % sent out | Coal burned(tons) |

| Umgeni | 1 197 | 1 129 | 216 | 64,4 | 683 698 |

In 1964, by the time the new Ingagane Power Station outside Newcastle had come on stream, electricity sales in Natal had increased by 14,9% to 2 922 million units. Main increases were due to supplies to the Durban Corporation, the Pietermaritzburg Corporation, the South African Railways and Feralloys Ltd works at Cato Ridge.

The remainder of the 1960s saw Umgeni adding several 132 kV feeders for the Durban Corporation, as well as other customers. During this period, the power station might well have ended up being called the Phillip Frame Park Power Station. In 1963, the New Germany Town Council wanted to change the area’s name to honour a prominent local businessman. Controversy raged until the Town Council backed down and called the industrial area, east of the power station, Phillip Frame Park.

During the winter of 1971 all of Natal’s power stations operated at maximum capacity to meet the load without major assistance from the Transvaal power stations. However, new technologies allowed an integrated high-voltage system to be built. It was becoming possible to build bigger power stations on the coal-fields and transport electricity. Large power stations, built on the Eastern Transvaal (now known as Mpumalanga) highveld, resulted in savings and increased efficiency. As it was, the Natal stations’ interconnection with the large pithead power stations in the Transvaal had been further facilitated by means of a second 400 kV line from Camden and Chivelston. This allowed the older and less efficient Congella and Colenso stations, as well as Umgeni, to reduce their output.

In 1971 Durban experienced one of its worst power failures. A fault near the Georgedale sub-station caused both transmission lines from Ingagane to trip. This substation had to be isolated from the system and the load switched to Congella, Umgeni and Colenso. This caused Umgeni to trip out on overload.

During this decade, the generation of electricity in South Africa increased by about 8% a year and by 1981 the country was using about 100 000 GWh a year, compared to approximately 22 500 GWh twenty years before. During the same period, per capita consumption of electricity trebled, from 1125 kWh to 3500 kWh.

Umgeni continued to contribute to this growth. 1973 statistics reveal the following:

(The reduction in output from over 1 000 GWh in 1971 to below 400 in 1973 was the result of the interconnection with the 400 kV grid).

| Units generated GWh | Units sent out GWh | Max demands 1 hour sent out MW | Overall thermal efficiency % (sent out) | Availability | Total water consumed (litres/USO) | Coal burnt (metric ton) |

| 432,6 | 392,9 | 221,6 | 19,3 | 83,0 | 4,46 | 279 311 |

The units of electricity transmitted from Umgeni power station constituted some 10% of the total units transmitted from Natal’s four power stations. Umgeni’s output equalled the combined output from Congella and Colenso power stations.

The newer and more powerful Ingagane provided 80% of the total. By this time, the power station’s first superintendent, Mr. Fred Hanlon had retired after 42 years’ service. The Assistant Superintendent, Mr. Jack Kelly was promoted to the post and occupied it between 1971 and 1973, by which time he had completed 37 years service. Mr. Colin Healey, who remained in the position until the power station was taken out of commercial service at the end of 1988, succeeded him. Mr. Healey also arranged for Umgeni power station to be the base for South Africa’s first steam preservation society, the Umgeni Steam Railway. The society began with a steam locomotive of 1893 vintage from Colenso power station. By 1984, this society was running train trips for the public from Sarnia to Umgeni.

The 1970s saw ESCOM’s entire Southern Natal Headquarters moved to a new building, adjacent to the power station, which at that time was also being used for pollution control tests. There were pollution issues demanding attention. Smoke emissions frequently resulted in public complaint. Grit arrestors drastically reduced this problem. Smoke emissions from Umgeni were just inside the legal limit, and were much less than the emissions from other local industries that burned smaller amounts of coal. Ash disposal involved either recycling it to make blocks, using it to reclaim parts of Durban harbour. The staff also dealt with complaints of excessive noise coming from the station. In one case, residents living about a kilometre away were woken early in the morning by the “blowing off” of steam. Special silencers were then fashioned to solve the problem. There were no difficulties with water pollution. The power station’s supply was drawn from the Durban Corporation in the form of potable water. In 1983, the severe drought and the Durban Corporation’s shortage of water led to Umgeni shutting down for a time.

The ‘social life’ of Umgeni power station differed from stations such as Ingagane and Colenso. The location of these power stations meant that they were essentially self-contained communities. The fact that Umgeni was situated in an urban setting meant that its employees were spread out and tended to be involved in sporting and recreational activities in their respective residential areas. Umgeni and Congella employees did at times collaborate on recreational events such as an annual Christmas Tree and a range of sporting activities including soccer, badminton, basketball, cricket and darts.

DECOMMISSIONING

By the 1980s, more powerful, efficient and cost-effective power stations in the Orange Free State (now known as Free State) and Transvaal were supplying the most of the country’s electricity needs. In addition, there was an oversupply of electricity. Demand had decreased and thus the older power stations were no longer required. More than half of Eskom’s power stations were affected by a downscaling exercise. Eleven stations altogether were to be taken out of service to be mothballed or decommissioned. Umgeni was one of these stations.

In 1985, the decision was taken to decommission Umgeni Power Station. For three years, the staff experimented with methods of mothballing the boilers. Eventually, in 1988, the decision was taken not to retain the station. Its machinery was to be either exported or sold as scrap in South Africa. There was nothing wrong with the power station, it was simply a matter of mothballing being too expensive in the long-term. For a time, Durban Corporation considered taking over the station for use during peak periods. However, this option was not pursued.

December 1985 to June 1988 saw the power station scarcely used. During this period, the staff complement of 500 was reduced to a skeleton staff of about 100, who oversaw the decommissioning and dismantling. Those who left Umgeni, were redeployed within Eskom, while others took early retirement. The official closing down ceremony took place on 9 February 1989. At an event attended by dignitaries from Eskom, New Germany and Pinetown, Eskom’s General Manager Generation Mr. Paul Semark shut off the steam supply, thus ending 35 years of operation. Evidence of Umgeni’s presence and purpose would remain for another five years. The hazardous task of removing the asbestos lagging to the boilers and steam pipes had to be carried out.

At the end of 1992, the cooling towers, a symbol of industrial expansion and economic well being to many, and an eyesore to some, were imploded to make way for an industrial township. On 12 June 1994, the three 108m smokestacks were also demolished. The demolishers, Wreckers Dismantling, packed approximately 175 kg of gelignite into the structures to implode them. And with that, this ‘gentle old lady’ was no more.

The feelings of those who worked in the power station and cared for it were summed up by Mr. Healey:

It was a…painful process for those who put their heart and soul into its smooth operation over the last 35 years…It breaks one’s heart. People have spent so much time caring for the machinery, seeing that it runs efficiently – only now to see it all smashed

APPENDIX

Mr Fred Hanlon started work with ESCOM as a switchboard attendant at Congella power station on the 1st July 1928, after having served an apprenticeship as an electrician with the Durban Corporation. He was promoted to Shift Engineer on 1st October 1936, to Operating Assistant on 1st January 1949, and to Assistant Power Station Superintendent, Congella on the 1st May 1950. On the 1st January 1954 he became the first Superintendent of the new Umgeni power station.

Mr. Jack Kelly joined the Electricity Supply Commission as a fitter at Colenso power station on 9th September 1938. His starting rate of pay was 3/d per hour. On the 27th August 1952, he ac-cepted the position of Operating Assistant at the new Umgeni power station that was then under construc-tion. Due to delays of delivery of major plant, he was not able to take up his post until the 8th January. He obtained his Mechanical Engineers Certificate of Competency on the 16th November 1960 and six weeks later was promoted to Assistant Power Station Superintendent. On the retirement of Mr. Hanlon, Mr. Kelly was appointed Power Station Superintendent from 5th July 1970 and was registered as a Professional Engineer on the 11th November 1971. He retired in 1973.

Mr. Colin Healey originally joined ESCOM as a shift engineer in 1959. He left its employ in 1961 but returned to the East London power station in 1968. Having been appointed Assistant Superintendent there, he was promoted to Superintendent of Umgeni power station and took up this post in January 1974. He retired with Umgeni’s closure in 1988. Mr. Healey was instrumental in providing a base for South Africa’s first steam preservation society, the Umgeni Steam Railway, at Umgeni Power Station.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

This information on Umgeni Power Station was produced by Stephen Leech, a historical researcher at University of Durban/Westville.

- Annals of New Germany (Compiled by the New Germany Women’s Institute, Killie Campbell Africana Library)

- Beinart, W Twentieth-century South Africa, Oxford (Oxford University Press, 1994)

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Information Republic of South Africa: 20 years of progress (Tri-Rand/Litho Co, Pretoria, 1981)

- Electricity Supply Commission’s Annual Reports

- Eskom News

- Megawatt

- Natal Undertaking Manager’s Annual Report

- Robinson, P A History of New Germany, 1848 to 1973 (UNP MA, University of Natal, Pietermaritzburg, 1973)

Newspapers:

- Daily News

- Highway Mail

- Natal Mercury

- Sunday Times

- Sunday Tribune

Interviews:

- SABC TV interview with Mr. Colin Healey, February 1989

- Interview with Mr. Colin Healey, 1 November 1999