West Bank Power Station

OVERVIEW

The original West Bank Power Station was built by the East London Harbour Board in 1905. The East London Municipality took a 30 year lease on the site and buildings in 1909 and installed their own plant, some of which was transferred from their East Bank Power Station which had been commissioned in October 1899. Additions were made at various stages, including during World War II (1939-1945), and the lease agreement extended. At the end of the war the installed plant capacity was 24,5 MW. ESCOM took the station over as from 1 January 1947 and increased the installed capacity to 32 MW in 1951. All turbo-generators at West Bank 1 were Brush Ljungström sets. A new power station, West Bank 2, was built on an adjacent site purchased from the Railway Administration and the first station re-named West Bank 1. The initial installed capacity of West Bank 2 consisted of two 15 MW generators commissioned in 1956. The station was extended to an ultimate capacity of 85 MW by March 1969, consisting then of three 15 MW sets and two 20 MW sets and six boilers.

West Bank was linked up to the 400 kV national network at the end of 1973. West Bank 1 was decommissioned in May 1978 and demolished the following year. West Bank 2 was taken out of commercial service at the end of 1988 and a formal closing ceremony was held on 10 February 1989. The plant was then sold as scrap and the building demolished.

The total net electricity production for stations 1 and 2, from 1947, the year West Bank was taken over by ESCOM, until closure amounted to 8 460 GWh and the coal burned amounted to 5,448 million tons.

ORIGINS

West Bank Power Station was located in East London, which is today an important harbour in the Eastern Cape Province. East London was originally founded as a military camp in 1847, became a Municipality in 1873 and was elevated to the rank of city in 1914. In February 1883, shortly after Kimberley had electric streetlights, an offer from the South African Brush Electric Light Company for electric street lighting of the town was accepted. However, the contract was cancelled in October 1883, at the request of the contractor. Fourteen years later, in 1897, Messrs Reunert and Lenz, Ltd. were contracted to build a power station on the east bank of the Buffalo River. It became known as the East Bank Power Station and was built at First Creek, where the Princess Elizabeth Graving Dock now stands. It was to supply power for lighting as well as an electric tramcar system. Reciprocating steam engine driven generators generated power. On 5 October 1899, the first twelve streetlights were switched on. It was intended that inauguration of the street lighting and the tramways should take place simultaneously, but due to delays in the delivery of the tramcars the tram service was not formally opened until 25 January 1900. The street lighting originally consisted of 20 arc lamps and 283 incandescent lamps. The tram service initially had three double decker cars, increasing to a fleet of 15 cars by 1903. At the end of February 1900, there were 182 private consumers receiving electricity. (East London Municipality Minute Book 1883:16&191; National Archives ref. 3ELN 1/1/1/4&5]; Daily Dispatch 6 October 1899, Evening Edition: 3& 9; Centenary Programme, 1848-1948:79; Tankard 1989).

Details of the plant originally installed at East Bank Power Station are as follows:

(Daily Dispatch – 6 October 1899 – Evening Edition – Page 3)

Distribution voltage for private mains: 2 000 V converted to 110 V at transformer houses

Coal source: Colonial (by rail) or imported (delivery by barge)

Each of the dynamos could light up to 120 arc lamps or drive up to 6 trams.

Demand soon began to outstrip the installed capacity of East Bank Power Station and the plant was augmented in 1902 and again in 1904. In August 1905 a new Town Electrical Engineer, JM Lambe, was appointed in East London. He submitted a report to the Town Council on the state of East Bank. Serious construction defects in the buildings led Lambe to recommend the erection of a new power station and the transfer of the plant to it. During the flood of October 1905, the power station was flooded and the town was temporarily without lights or trams. The floodwaters reached a height of 13½ feet [4,1 m] above low water. (Harbour Board Report 1905:33 [G.33-1906]; The Electrician Vol LVII:151&311, 11 May 1906 & 8 June 1906; (Centenary Programme, 1848-1948:37&79; Daily Dispatch 12 October 1905)

The East London Harbour Board built their own power station, which was commissioned in 1905, on the west bank of the Buffalo River. In accordance with a decision of the Colonial Parliament, the East London Harbour was taken over by the Railway Department on 1 January 1909. On 31 May 1909, the power station as well as the machinery and certain cables across the Buffalo River, were taken over “in thoroughly good working order” from the Government by the East London Municipality. However, the site and building remained the property of the Government, being leased to the Municipality on a 30-year lease of £600 per annum. An agreement was entered into for the supply of electric power to the Government from the power station, which became known as the West Bank Power Station. The installation of additional equipment was completed at the end of 1910. The station was fitted out with four ‘Yates and Thom’ Lancashire-type boilers and Brush Ljungström turbo-generators. On 28 February 1911, with West Bank carrying the full load, East Bank Power Station was closed down. The electricity generated for the last year that East Bank was in operation – 1909/10 – was 1,066 GWh and the electricity sold 0,878 GWh. The maximum demand supplied was 0,74 MW. (Annual Report of the Commissioners of the East London Harbour Board for the year 1905:34 [G.33-1906]; Annual Report of the General Manager of Railways 1909:16, (I) (Roman fifty) [G13-1910]; Centenary Programme, 1848-1948:79; Denfield 1965:77):

The Ljungström (pr. yung-strauom (Swed)=heather river) turbines were radial flow reaction turbines, invented by Birger Ljungström (1872-1948) and patented under British Patent 7833:1907. Frederik Ljungström and others further developed the design. The steam flow was outwards from the shaft, with blades mounted on two wheels rotating in opposite directions. There were no fixed blades. Each wheel was coupled to an alternator that carried half the load. An outstanding feature was the extreme compactness of the design. The Ljungström turbine was manufactured under licence by Svenksa Turbinfabriks Aktiebolaget Ljungström (STAL) in Sweden, and Brush Electrical Engineering Co in England. Sets as large as 65 MW were installed in Sweden in 1949. Vaal Power Station had three 33 MW Ljungström sets ordered from the Swedish firm ASEA before World War II, but delivered after the war. There were also three 7 MW Ljungström house sets at Vaal. King William’s Town Power Station had two 1,5 MW Brush Ljungström sets when taken over by ESCOM in 1948. (ESCOM Twenty-five Years 1923-1948:46&48; 1949:211-218; Auger 1965:65; ESCOM Megawatt No.30/1974:12; Hanks & Hodges 1988:330; McGraw-Hill Dictionary of Engineering 1997:301)

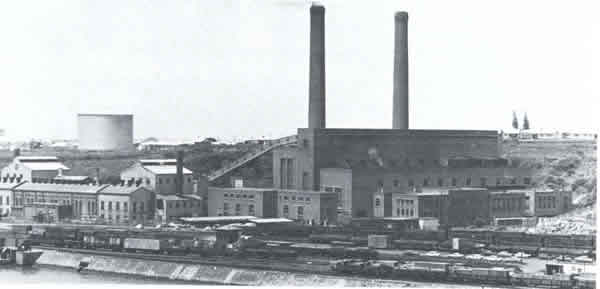

West Bank 1 Power Station in late 1940s

WEST BANK IN OPERATION

With the new supply of electricity demand continued to increase. Electricity sold in 1911 amounted to 1,215 GWh. In 1918 the installed plant capacity was 1,7 MW and the electricity sold that year was 1,596 GWh. Generation was at 50 Hz ac and at 550 V dc. The 1920s saw the number of consumers in East London double and the amount of electricity sold increase by 175%. Although delayed by the First World War, new equipment was installed in 1923/24 including two Babcock and Wilcox boilers and two Brush Ljungström turbo-alternators at a cost of £76 000. By 1928 the original plant in the power station was nearly thirty years old and in a deteriorated condition. Lambe proposed the replacement of this equipment and further additions. The old plant was dismantled and sold in 1928 and two new boilers and another turbo-alternator installed in 1929/30. These additions enabled the power station maximum load to increase from 1,5 MW in 1923, to 3,0 MW in 1930. In 1933 the plant consisted of four Babcock and Wilcox boilers rated at 21 500 lb/h [2,71 kg/s] and 220 lb/sq.in. [1,62 MPa (abs)] and three Brush Ljungström turbo-alternators (two at 1,5 MW and one at 3,0 MW). Another turbo-alternator was planned for installation before the end of 1934. During 1935 diesel busses were introduced and trams were phased out, reducing the load on the power station by about 0,7 GWh per annum. Any further additions with larger generators would necessitate extensive additions to the buildings and the demolition of the 140 foot [43 m] brick smokestack then no longer in commission. As the site and buildings were not the property of the Council, and the lease agreement had only another seven years to run, negotiations were again started for the acquisition of the site and buildings. The expiry date of the lease agreement was 30 September 1940. However, the Government would not transfer the site outright to the Municipality but agreed to extend the lease from 1 October 1940 for another 30 years, with the option of a further 30-year extension. (Merz and McLellan 1920:37; Centenary Programme, 1848-1948:79; Report by JM Lambe printed in Daily Dispatch 20 October 1933:3).

Extensions made | Total capacity | Year | Maximum load |

1923/24 1929/30

1935 1940 7,5 MW generator 5 1945 7,5 MW generator 6 | 3,0 MW 6,0 MW

10,0 MW 17,0 MW 24,5 MW | 1923 1928 1930 1933 1934 1940 1947 | 1,5 MW (generated) 2,5 MW (generated) 3,0 MW (generated) 4,2 MW (generated) 4,5 MW (generated) 8,5 MW (generated) 15,9 MW (net) |

The addition of a 7,5 MW Brush Ljungström turbo-alternator in 1940 enabled the station load to be increased to 10 MW by 1941. In 1945, another 7,5 MW Brush Ljungström turbo-alternator was installed.

(Centenary Programme, 1848-1948:79; Daily Dispatch 20 October 1933:3)

The boilers were fired by chain grate stokers, the coal burnt being ‘washed peas’ (sizing 6 to 19 mm) of calorific value between 28 and 29 MJ/kg, and railed from the Natal coal-fields. (Daily Dispatch 20 October 1933:3; ESCOM Twenty-five Years 1923-1948:47 and ESCOM Annual Reports – Tables of power station operating statistics). Situated on the bank of the Buffalo River, West Bank drew its circulating water from the river. However, this location also had negative consequences in that floods occurred at various intervals. The years 1905, 1922, 1948, 1953, and 1970 were particularly notable for flooding in the area. There were also severe droughts in 1927 and 1945-47 when water for domestic consumption was available for only one hour per day. Water for boiler make-up had to be transported to West Bank. (Centenary Programme, 1848-1948:73)

Flood pictures in 1970 :

WEST BANK TAKEN OVER BY ESCOM

After the Second World War (1939-1945) South Africa’s economy expanded rapidly. Manufacturing and commerce in particular began to boom. The power supply industry was severely handicapped by the shortage of generating capacity and distribution equipment to meet the widespread demand for electricity from the pent-up requirements of all classes of consumers. In 1946 the Municipality of East London requested ESCOM to take over ownership and operation of the West Bank Power Station, and to supply the Municipality in bulk. A number of other municipalities had also approached ESCOM for supplies. ESCOM then established the Border Undertaking which would be developed to cope with the electricity demands over an area extending to a radius of approximately 200 km from the power station at East London. ESCOM purchased West Bank Power Station from the Municipality and assumed ownership from 1 January 1947, although until August of that year the Municipality continued to operate the station on behalf of ESCOM. ESCOM then took over operation and complete control, and the employees at the power station were transferred to Escom. (ESCOM Annual Reports 1945:6; 1946:6; 1947:7&53; ESCOM Twenty-five Years 1923-1948:29&30).

However, the available generating capacity in the newly-established Border Undertaking was insufficient to meet the anticipated demand. A new power station was required. A site for a new power station had previously been acquired by the East London Municipality from the Railway Administration. It was adjacent to the existing station, and was transferred to ESCOM when West Bank Power Station was taken over.ESCOM proposed to use this site for a new station to be known as West Bank 2, and the existing station would be known as West Bank 1. (ESCOM Annual Reports 1946:6; 1947:7; 1949:9&27

OPERATION OF WEST BANK 1 AFTER TAKE-OVER BY ESCOM

Further expansion of West Bank 1 would have to take place until the new station was ready. By 1948, a 7,5 MW generator (no. 7) and two 55 000 lb/h [6,93 kg/s] boilers (nos. 9&10) were on order for installation at West Bank 1. The boilers were in service by July and August 1951 and the generator brought into operation in November 1951, the generator voltage being 11 kV. Generator 6, previously generating at 6,6 kV, was re-connected in 1952 to also generate at 11 kV. West Bank 1 had then reached its final installed capacity of 32 MW. In 1953 the heaviest rains on record occurred causing unprecedented flooding. There were two total interruptions of supply and a number of partial failures at West Bank 1 as a result of the storm and flood conditions. (ESCOM Annual Reports 1948:41; 1951:38; 1952:32 &1953:32).

Net generation of electricity at West Bank 1 in 1947, the first year after ESCOM had taken the power station over, was 55,8 GWh and the net maximum power produced was 15,9 MW. In 1952, the first full year with the station at its final installed capacity of 32 MW, the figures were 87,6 GWh and 20,0 MW. By 1954 net generation was 105,3 GWh. During 1955 the boiler plant at West Bank 1 was assisted by steam from boiler 1 at West Bank 2 and net generation for that year was 116,3 GWh. This was the maximum annual production at West Bank 1 because West Bank 2 was in commission the following year. By 1958 West Bank 1 contributed only 13,4% to the production in the Border Undertaking and this figure had dropped to 5,5% in 1960. (ESCOM Annual Report 1958:30).

Modifications to the boiler plant at West Bank 1, to improve combustion difficulties, were carried out in 1958. Economisers were fitted on boilers 7, 8, 9 and 10 during 1966 to improve the efficiency. A blade failure occurred on turbo-alternator 7 at West Bank 1 in September 1961. The turbine was sent to the maker’s works for new blades and was returned to service in April 1963. Turbo-alternator 6 blades failed in August 1963 and the turbine was also sent to the makers for reconditioning. (ESCOM Annual Reports 1958:30; 1963:45 &1966:33).

Further statistics for these years are given below.

| YEAR | Net Generation GWh | Net Max Power MW | Load Factor (net basis) % | Thermal Efficiency net basis % | Coal Consumed metric ton | Calorific Value of Coal MJ/kg | Cost of Coal R/metric ton | Net Water consumption litre/kWh |

| 1947 | 55,8 | 15,9 | 42,0 | 16,0 | 42 863 | 29,35 | 2,94 | Not available |

| 1952 | 87,6 | 20,0 | 50,0 | 15,1 | 72 389 | 28,82 | 3,75 | Not available |

| 1954 | 105,3 | 23,3 | 51,6 | 14,0 | 96 266 | 28,12 | 4,17 | Not available |

| 1955 | 116,3 | 25,2 | 52,6 | 13,6 | 110 378 | 27,98 | 4,61 | Not available |

The principal equipment taken over by ESCOM at West Bank consisted of the following:

| Boilers: | Manufacturer | Capacity | Pressure | Temperature |

| Nos. 1-4 | Babcock & Wilcox | 21 500 lb/h [2,71 kg/s] | 220 lb/sq.in. [1,62 MPa (abs)] | 580 °F [304 °C] |

| Nos. 5-6 | John Thompson * | 27 500 lb/h [3,46 kg/s] | 220 lb/sq.in. [1,62 MPa (abs)] | 650 °F [343 °C] |

| Nos. 7-8 | Stirling Co | 55 000 lb/h [6,93 kg/s] | 220 lb/sq.in. [1,62 MPa (abs)] | 720 °F [382 °C] |

| Generation Plant: | Manufacturer | Capacity | Voltage |

| Turbo-Alternator 1 | Decommissioned | ||

| Turbo-Alternator 2 | Brush | 1,5 MW | 6,6 kV |

| Turbo-Alternators 3 and 4 | Brush | 4,0 MW | 6,6 kV |

| Turbo-Alternators 5 and 6 | Brush | 7,5 MW | 6,6 kV ** |

| Total installed capacity | 24,5 MW |

** Generator 6 was re-connected to 11 kV in 1952 after generator 7 had been installed

The principal equipment installed by ESCOM after take-over consisted of the following :

| Boilers: | Manufacturer | Capacity | Pressure | Temperature |

| Nos. 9-10 | Stirling Co | 55 000 lb/h [6,93 kg/s] | 220 lb/sq.in. [1,62 MPa (abs)] | 720 °F [382 °C] |

| Generation Plant: | Manufacturer | Capacity | Voltage |

| Turbo-Alternator 7 | Brush | 7,5 MW | 11 kV |

| Total installed capacity | 32 MW |

CONSTRUCTION AND COMMISSIONING OF WEST BANK 2

After World War II, ESCOM was planning seven new power stations, Hex River, Vierfontein, Umgeni, Wilge, Taaibos, Salt River 2, and West Bank 2. The decision to establish the Border Undertaking and to build West Bank 2 was taken during the time of ESCOM’s founding chairman, Dr H J van der Bijl, who died in December 1948. Mr A M Jacobs, who was previously ESCOM’s Chief Engineer, succeeded Dr van der Bijl as chairman. Mr Jacobs decided that Hex River, Vierfontein and Taaibos would be designed by ESCOM’s own head office staff, but West Bank 2 would be one of the stations assigned to ESCOM’s consulting engineers, Merz and McLellan. West Bank 2 was the last of the seven new stations to be commissioned. Mr Jacobs retired in 1952, before West Bank 2 had been commissioned, and was succeeded by Dr J T Hattingh, who completed what Mr Jacobs had planned and started. The decision to increase the installed capacity of West Bank 2 to its ultimate capacity of 85 MW was taken during the chairmanship of Dr RL Straszacker, and the 400 kV national grid was also introduced during his term. The final downscaling of the power station began with Mr Jan H Smith as chairman and actual closure with Dr J B Maree as chairman. (ESCOM Annual Reports and 1950:9).

The proposed site for West Bank 2 Power Station was transferred to ESCOM when the existing station was taken over. Work to clear and drain the site being carried out by the Railway Administration, was seriously delayed by collapse of a section of the rock face during a violent storm in April 1948. The site was not expected to be ready for the start of civil work before the middle of 1951. The main plant on order in 1950 included two 15 MW generators and two 170 000 lb/h [21,4 kg/s] boilers at an estimated cost of £2,363 million, expected to be in operation by the first half of 1955. In 1952 the estimated costs, including civil works, were revised to £2,6 million. There were further delays in 1953 due to shortage of labour and material, and exceptional storms. (ESCOM Annual Reports 1946:6; 1948:30; 1949:9; 1950:10; 1951:12; 1952:8; 1953:8).

A steam interconnector was planned to pass steam from the new to the old station, and it was hoped that the first boiler at West Bank 2 would be steaming by May 1955 to give assistance to the old station. Load shedding, a process that causes interruption in electrical power supply to some consumers, had been necessary during July and August 1954. However, the planned steaming date was delayed by shortages of labour and material. Load shedding was again necessary in June 1955 due to a shortage of steaming capacity. Although not fully completed at the time, boiler 1was first steamed on 26 June 1955 in order to make up the shortfall at West Bank 1. (ESCOM Annual Reports 1954:13&34; 1955:12&35).

West Bank 2 first generated power on 26 April 1956. From July 1956 there were two 15 MW generators and two boilers in service. A 66 kV interconnector was built between East London and King William’s Town, and by the end of 1956 West Bank was supplying the whole of the Border Undertaking’s requirements. The steam interconnector between West Bank 2 and West Bank 1 enabled major overhauls and repairs to be carried out at West Bank 1. The new boilers used a different grade of coal (mixed smalls: sizing 0 to 25 mm) which was being purchased from the Witbank area in the Eastern Transvaal (now Mpumalanga). The calorific value was lower (approximately 26,5 MJ/kg instead of previously 28,5 MJ/kg) but the price, including railage, was cheaper. (ESCOM Annual Report 1956:9, 33&104 and Tables of power station operating statistics).

Inquiries were issued in 1956 for a third set and boiler for commissioning about 1960. However, due to the East London Municipality achieving a reduction in maximum demand by installing “Ripplay” load control for water heaters, the order for the generator was postponed, but the boiler was considered justified. Erection of the third boiler, also rated at 170 000 lb/h [21,4 kg/s], was commenced in 1958. Equipment for chlorination of circulating water at the intake from the Buffalo River was installed during 1959, practically eliminating marine growth from the system. (ESCOM Annual Reports 1956:9; 1957:14; 1958:30&1959:13).

Boiler 3 was steamed for the first time in March 1960 and was placed in commercial operation in April 1960. Erection of the third generator, a 15 MW set supplied by Oerlikon, commenced in 1962 and the generator was placed in commercial operation in September 1963. Several factors had delayed the commissioning, and it was not available for the winter as planned. Capital costs of West Bank 2 with three 15 MW sets amounted to R156 per kW installed. (ESCOM Annual Reports 1959:13; 1960:33; 1962:41; 1963:45; 1965:8).

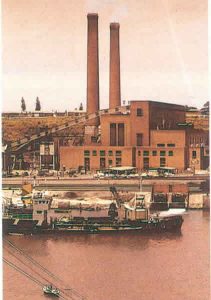

A fourth 170 000 lb/h [21,4 kg/s] boiler was ordered in 1964 and cyclone separators were installed in boiler 2 to replace the plate-type steam scrubbers. These proved effective in eliminating the water carry-over, which had previously led to superheater tube failures in boilers 1 and 2. The fourth boiler, a spare, was designated boiler 7, and was commissioned in August 1966 and placed in full operation in October 1966. Civil works for the “D” extensions, to accommodate a 20 MW generator (no. 4) and a 210 000 lb/h [26,5 kg/s] boiler, were proceeding in 1965. A second chimney stack was in construction due for completion in August 1967. A diesel locomotive wascommissioned in June 1966 to facilitate shunting of coal trucks. (ESCOM Annual Reports 1963:45; 1964:32 &1966:33).

The first 20 MW generator (no. 4) was in commission in June 1967 and the associated boiler (designated boiler no. 4) in August 1967. The second 80,5 m brick chimney stack was completed in April and was placed in service in July 1967. During the year contracts were awarded for an additional 20 MW generator (no. 5) and 210 000 lb/h [26,5 kg/s] boiler (designated no. 5) for commissioning at the end of 1968 and beginning of 1969 respectively. This would be the “E” extension and the generator and boiler were commissioned in March 1969. The station was then at its final installed capacity of 85 MW and future needs were planned to be supplied from the national 400 kV network. (ESCOM Annual Reports 1967:33; 1968:38 &1969:19).

The principal equipment installed at West Bank 2 was as follows:

| Boilers: | Manufacturer | Rating | Date commissioned |

| 1 | Daniel Adamson | 170 000 lb/h [21,4 kg/s] | June 1955 |

| 2 | Daniel Adamson | 170 000 lb/h [21,4 kg/s] | July 1956 |

| 3 | Yarrow | 170 000 lb/h [21,4 kg/s] | March 1960 |

| *7 | Yarrow | 170 000 lb/h [21,4 kg/s] | August 1966 |

| 4 | Yarrow | 210 000 lb/h [26,5 kg/s] | August 1967 |

| 5 | Yarrow | 210 000 lb/h [26,5 kg/s] | March 1969 |

* The fourth boiler, a spare, was designated no. 7

| Generators: | Manufacturer | Rating | Voltage | Commissioned |

| Generator 1 | Metropolitan-Vickers | 15 MW | 11 kV | April 1956 |

| Generator 2 | Metropolitan-Vickers | 15 MW | 11 kV | July 1956 |

| Generator 3 | Oerlikon | 15 MW | 11 kV | Sept 1963 |

| Generator 4 | Oerlikon | 20 MW | 11 kV | June 1967 |

| Generator 5 | Hitachi | 20 MW | 11 kV | March 1969 |

| Total installed | 85 MW |

The first full year of production at West Bank 2 was in 1957. Electricity transmitted from the combined stations 1 and 2 amounted to 144,5 GWh and the efficiency had improved from 13,6% in 1955 (Station 1 only) to 19,4% (combined stations) in 1957. The highest net efficiency achieved by the combined stations was 23,4% in the year 1971. The highest net generation was 516,0 GWh and was produced in 1973, the year before the Undertaking was linked to the 400 kV system.

The coal burned that year amounted to 294 844 tons. The following year, as a result of the interconnection with the 400 kV network, production dropped to less than half this amount. The highest net maximum power produced (maximum demand) was 107 MW, in the year 1975. The assigned sent out rating that year was 101 MW (80 MW for West Bank 2 and 21 MW for West Bank 1). The last year of significant generation was 1985, when net production was 100 GWh. The coal burned over the last three years of operation, 1986 to 1988, amounted to only 16 568 tons, as compared with 64 264 tons in 1985. (ESCOM Annual Reports 1975:49 and Tables of power station operating statistics).

The total net electricity production for stations 1 and 2, from 1947, the year West Bank was taken over by ESCOM, until closure amounted to 8 460 GWh and the coal burned amounted to 5,448 million tons. (ESCOM Statistical Yearbook 1995:15). Additional statistics are given below.

| YEAR | Net Generation GWh | Net Max Power MW | Load Factor (net basis) % | Thermal Efficiency net basis % | Coal Consumed metric ton | Calorific Value of Coal MJ/kg | Cost of Coal R/metric ton | Net Water consumption litre/kWh |

| 1957 | 144,5 | 30 | 54,9 | 19,4 | 100 639 | 26,59 | 4,61 | Not available |

| 1971 | 408,0 | 80 | 58,0 | 23,4 | 229 622 | 27,36 | 6,31 | 0,21 |

| 1973 | 516,0 | 101 | 58,3 | 23,0 | 294 844 | 27,36 | 8,17 | 0,18 |

| 1975 | 272,3 | 107 | 30,8 | 20,6 | 177 100 | 26,88 | 11,33 | 0,46 |

| 1985 | 100 | 81 | 14,3 | 21,4 | 64 264 | 26,21 | Not available | 3,81 |

The power station ash was removed from site by road, most of it being taken by the Municipality for landfill and road construction. When the power station closed down, the surplus coal was sold and railed to brickfields. The power station staff loaded the trucks. (K Beckmann 2002).

When ESCOM took West Bank over in 1947, East London’s Municipal Electrical Engineer, Mr Arthur Foden, remained in charge of the power station in a dual capacity. He was both East London Municipal Electrical Engineer and the Border Undertaking Manager.

By 1954, power station staff, then under the leadership of Mr Norman Curry as power station manager, had to overcome numerous difficulties with West Bank 1 due to the boilers experiencing poor grate and ash dumping conditions. This resulted in load shedding in July and August. Extra secondary air fans were fitted in order to improve the boiler performance.

The staff complement of 185 served both stations. One cycle of shift-work would be performed at Station 1, the next at Station 2. The staff enjoyed both good working conditions and an active social life. There was a clubhouse at West Bank 2 for playing indoor games such as darts and snooker. The snooker table was relocated to the nearby Port Rex Power Station when West Bank 2 was closed down. For outdoor sports such as soccer, cricket and hockey, staff members joined local clubs. The cricket team did particularly well, playing in the East London league. A variety of fish were attracted to the warmer water at the circulating water outlet and were a boon for anglers. Fishing was a favourite lunch time occupation for staff.

Numerous characters stand out, among them the ‘V8 kid’ Norman Daniels, the station chemist. A small man with a very large car (a Dodge Monarco), he always had a ready smile despite suffering from severe arthritis. Another was a staff member who used to raffle his pay packet and make a considerable amount of money until this particular means of increasing one’s income was stopped. ‘Scotty’ the carpenter also stands out as someone always willing to assist. One of the operators at West Bank went on to become local singer Tommy Dell. It was individuals such as these that made for a strong sense of community and enjoyable working conditions.

During the 1960s, management at the power station changed twice. In 1963, Mr Ron Appel took over, followed by Mr Lindsay Carswell, who had served his apprenticeship at West Bank, returning as manager in 1967. He had to contend with a severe flood in August 1970. Heavy rains started on Monday, 24 August 1970, and by Friday evening 28 August 1970, more than 700 mm had fallen, causing devastation in the area. A dramatic – but incorrect – report was received that the Bridle Drift Dam, 25 km higher up the Buffalo River, had burst and a 24 m high wall of raging water was about to engulf the harbour. The order was given to shut the power station down and evacuate. The whole of East London was blacked-out and remained without power from 19:00 until 21:00, when it was confirmed that the dam was not in danger. Immediately, senior staff began to gather employees and they headed back to the station that was soon underway again. Nevertheless, the station was flooded to a depth of 600 mm above ground level and considerable damage was caused. The railway supply line was partly washed away and took five days to repair, leaving only one day’s supply of coal! (Daily Dispatch; ESCOM Megawatt No.18/1970:12-15).

West Bank achieved 12 months without a disabling injury by 18 June 1972. By October the station had chalked up one million injury-free man-hours, and on 24 November 1972 Mr Lindsay Carswell was presented with the Manager (Operations) Trophy by Mr EE Robinson, the Deputy Senior Manager (Operations). For two successive years, 1972 and 1973, West Bank won the coveted 5-star Grading certificate awarded by the National Occupational Safety Association. In 1975 the station again won safety awards: the Mark Tennyson trophy for ‘good housekeeping’ and the Bert Kipling trophy for safety. On 18 August 1977, the Natal area trophy for the Area Accident Prevention competition was added to the collection.

In 1978 the General Manager’s Floating Trophy was awarded to West Bank for the best performance in the safety field in 1977. This was the second time this award had been made to West Bank – the first time was in 1973. Mr Lindsay Carswell was presented with the trophy at a function held on 28 June 1978. (ESCOM Megawatt No.26/1972:6; No.30/1974:34; No.37/1976:29; No.40/1977:23; No.50/1978:16).

Mr Howie Ellis succeeded Mr Lindsay Carswell as power station manager, and was followed by Mr Hans Pennells and then Mr Charles Green. They each ensured that West Bank continued to maintain high reliability and availability. Safety remained paramount.

DECOMMISSIONING AND CLOSURE

In 1970, Boilers 1, 2, 3 and 4 at Station 1 were placed in dry storage (a form of “mothballing” which would take longer than 24 hours to return to service). West Bank 2 had reached a capacity of 85 MW and the need to operate West Bank 1 was easing.

During the second half of the 1960s, ESCOM began construction of a 400 kV transmission system that would link all Undertakings throughout the country. The transmission of power at high voltage from large power stations situated at the coal-fields in the Eastern Transvaal (now known as Mpumalanga) was becoming a cheaper option than transporting coal to smaller power stations built at the main load centres. An amendment to the Electricity Act allowed ESCOM to establish the Central Generating Undertaking (the CGU) as from 1 January 1972, and to group together the power stations of the various previously existing Undertakings. This would enable ESCOM to obtain the maximum benefit from pooling. (ESCOM Annual Reports 1966:11&1971:6).

The Border Undertaking was not linked to the national 400 kV transmission network until the end of 1973 with the result that West Bank Power Station was not formally transferred to the CGU until 1 January 1974. Boilers 1 to 6 and generators 2 to 4 at West Bank 1 were then finally de-commissioned, reducing the installed capacity of the station to 22,5 MW. West Bank 1 remained on standby until May 1978, when it was completely decommissioned, and the following year it was demolished. Generator 7 had been in service for 26½ years and generator 5 for 10 years longer. (ESCOM Annual Reports 1973:5, 67&95; 1978:54).

In the latter half of the 1980s, ESCOM was experiencing a surplus of generation capacity and a number of the older and more expensive stations were shut down. In September 1988 the news came that West Bank 2 would close. Manager Charles Green had the unenviable task of closing the station. Morale was dealt a blow as staff found that they had to leave the power station they had cared for. One employee, Mr Peter Bezuidenhout had worked there for 33 years, the longest serving worker at the station. He started as Ashplant Attendant and advanced to Principal Plant Operator. Some staff members were retrenched, some took early retirement and others were re-deployed within Eskom.

On 10 February 1989 a closing ceremony was attended by various dignitaries including the Mayor of East London, Mr Donald Card, and Eskom’s General Manager of Generation, Mr Paul Semark. Guests gathered at the station where Mr Semark pushed a button that closed down one of the turbines. A light had been connected so that as the turbine slowed down, the light grew dimmer until it was dark. Thus ended 33½ years of service. In the darkness a lone bagpiper played, causing tears to be shed.

The employees left at the station then set about the task of asbestos insulation removal, which was done in accordance with Eskom policy and national legislation. It was loaded into the obsolete pump house basement, which had been sealed with concrete from the connections to the river. This work was completed at the end of 1990. Contractors then moved in to remove the equipment for scrap. Fred Potgieter, who had been at the station for 32 years, summed up the feelings of those who had worked there by commenting ‘Its so sad to see the old girl turned into so much scrap’.

By 1992, with the boiler house and turbine hall already demolished, the two chimney stacks still remained. On 31 October 1992, these two East London landmarks were demolished. A large crowd turned out to watch the demolition which ‘changed the face of the West Bank forever’. The following year, the site was put out to public tender and now awaits further development.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

This information on West Bank Power Station was produced by Stephen Leech, a historical researcher at University of Durban/Westville and Dick Fowler, a retired Eskom employee. Dick Fowler has produced additional research material that is available on request (see home page for contact details).

Published works

- A History of Technology (Edited by Trevor L Williams) Volume VII – Clarendon Press – Oxford, 1978

- Auger, CP – Engineering Eponyms – The Library Association – Staples Printers Ltd, Kent, England, 1965

- Carr, TH – Electric Power Stations Volume I, Third Edition – Chapman & Hall, London, 1947

- Conradie, SR & Messerschmidt LJM – A Symphony of Power – The Eskom Story – Chris van Rensburg Publications (Pty) Ltd, Johannesburg, 2000

- Denfield, Joseph – Pioneer Port – Howard Timmins, Cape Town, 1965

- East London Centenary Programme 1848-1948, Official Souvenir Brochure – The Municipality of the City of East London

- Electricity Supply Commission/Eskom Annual Reports, 1945 to 1988

- ESCOM: Megawatt No.18/1970; No.26/1972; No.30/1974; No.37/1976; No.40/1977; No.50/1978

- ESCOM: Twenty-five Years – A record of the origin, progress and achievements of the Electricity Supply Commission, 1923-1948

- Eskom Campus

- Eskom News

- Eskom: Statistical Yearbook 1995

- Hanks, Patrick & Hodges, Flavia – A Dictionary of Surnames – Oxford University Press, 1988

- McGraw-Hill Dictionary of Engineering, Fifth Edition, New York, 1997

- Merz and McLellan, 1920 – Electric Power Supply in the Union of South Africa

- Tankard, KPT – East London’s Tram Service 1900-1914 – In: The Coelacanth, The Journal of the Border Historical Society – Volume 27 No.2 Pages 17-27, December 1989

- Ljungström Dr F: The Development of the Ljungström Steam Turbine and Air Preheater. In: Institution of Mechanical Engineers (London), Proceedings, Vol 160, September 1949 (pages 211-223)

Unpublished works

Official correspondence of the East London Municipality, National Archives

Newspapers

Daily Dispatch:

- 6 October 1899:3 East London Town Hall and Electric Lighting

- 6 October 1899:9 The Electric Tramways; The Electric Lighting

- 12 October 1905:4 The Storm and the Harbour

- 20 October 1933:3 The Council and the Power Station

- 28 August 1970:1 City of Agony

- 29 August 1970:1 Rumours of Threat to Two Dams Squashed

- 2 September 1970:14 (Supplement) Harbour takes a Pounding

- 2 November 1992:1 Going, going, gone!

- 2 November 1992:2 W Bank smoke stacks demolished

Interviews

- Interview with Mr Bernard Lindstrom, 12 December 2001

- Interviews with Messrs Vivian Beckford, Willie De Beer, Selwyn Goddard, Ronald Gower and Ernest Manyanye, 13 December 2001

- Interview with Messrs Peter Filmer and Charles Green, 21 December 2001