Wilge Power Station

BACKGROUND

JT Hattingh succeeded Albert Jacobs as Chairman of ESCOM in 1952. His first task as chairman was to offer a long-term solution to electricity shortage problems. A task that Jacobs had planned and started.

After the Second World War South Africa became significantly more industrialised. The tremendous industrial growth and the post-war devaluation of the pound resulted in increased exports and demand on mining resources. Apart from the Witwatersrand goldfields, new industries and mining activities started up in this region. The Free State goldfield opened up, and in the Vaal Triangle the Iscor steel plant at Vanderbijlpark was founded.

The demand for electricity far exceeded the supply (an annual increase in demand of 10% on average was experienced from 1948) and severe power shortages were experienced. The supply area of the Rand and Orange Free State Undertaking was suffering the most. It was the largest of ESCOM’s undertakings in which most industrial and mining activities were concentrated.

From 1949 ESCOM asked consumers to effect voluntary restrictions of their operations during peak load periods. Also, in consultations with the Chamber of Mines, a scheme was introduced whereby each mine would receive a monthly quota of electricity based on the consumption of the previous three months. The supply to municipalities and other bulk consumers was also restricted.

To address the problem ESCOM constructed eight new power stations between 1952 and 1959 and expanded the six existing stations. In 1951 it became apparent the proposed extensions to the Rosherville power station would be inadequate to meet the additional loads and that the site would be unsuitable for the installation of the additional plant that would be required. The Rosherville extension was therefore abandoned and it was decided to transfer the plant on order for Rosherville to the site of a new power station to be situated near to the New Largo Colliery, in the Kendal/Ogies/Witbank area of the Transvaal (today Mpumalanga).

CONSTRUCTION

It was customary at that time to name power stations after the source of water; hence the station was named Wilge, after the nearby river Wilge. However, the actual source of water was the Bronkhorstspruit dam where a pump station was constructed to pump water over 17.5 miles to the power station.

Wilge power station was situated near Ogies on the Witbank coalfields. This ensured a plentiful supply of coal, nevertheless, the size of the station had to be restricted to 240 MW because of limitations on the water supply.

At a time when designers of power stations were making every effort to save money; it could be asked how a station of this small size was justified. The simple answer is that the urgency of the demand for power outweighed the demand for economy.

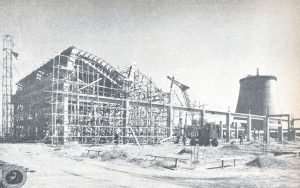

Main station building under construction . Boiler erection crane in foreground

At that time South Africa had huge reserves of uranium locked up in the same ore structures as gold. Many gold mines, therefore, started uranium by-product operations. This was an energy-intensive process and required an additional power station at short notice.

Because the demand for power for uranium production was of such a high priority, factors such as cost and water supply were ignored.

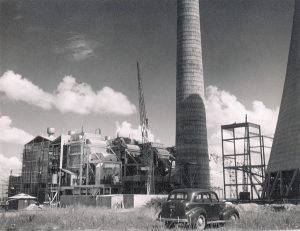

In 1953 work began on the laying of the pipe line from Bronkhorstspruit dam, the construction of the make-up water pump house at the dam, the erection of steelwork for turbine house No. 1 and for boilers Nos 1 to 4. The erection of workshops and construction of railway tracks from the Colliery siding began.

COST

It was planned to have the station completed by the end of 1955 at an estimated cost of £10,327,000, which was revised to £10,800,000 even before construction started.

TRANSMISSION SYSTEM

A transmission system of 132 kV stretching over 41 circuit miles from Wilge power station to the Struben distribution station was completed in 1955. On the Wilge power station – Bronkhorstspruit dam line, carrier equipment for control of the pump was installed. Two 21 kV cables were laid from Wilge power station to complete the outgoing feeders. A special linking substation was provided at this point to enable supplies to be maintained in the event of the failure of one of the cables.

OUTPUT

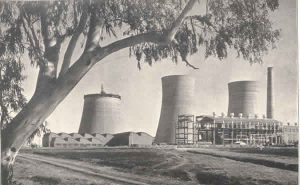

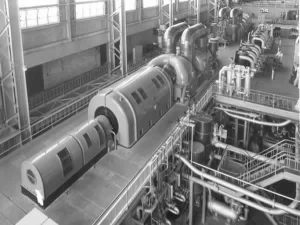

The planned capacity of the station was 180,000 kW, to be provided by two 30,000 kW and two 60,000 kW turbo-generators with four spreader-stoker type 150,000 lb/hr boilers and four 400,000 lb/hr pulverised fuel type boilers. The initial installation of one 30,000kW turbo-generator and two 150,000lb/hr boilers was scheduled to be in operation by September 1953, but was only completed in February 1954. The second 30,000kW set and two additional 150,000lb/hr boilers were ready by July 1954 and February 1955 respectively. The first 60,000 kW turbo-generator, with the two large boilers (Nos 5 and 6), were completed and taken into service in July-August 1955. No 7 boiler was steamed on 2 March 1956, and No 8 boiler on 6 April 1956, and the second 60,000 kW machine (No 4) was commissioned on 9 April 1956. An additional water supply had been granted to the Commission from the Bronkhorstspruit Dam, and the station was to be extended by the addition of a third 60,000 kW turbo-generator and one 550,000 lb/hr boiler. Orders for this plant were placed with A.E.G. Germany and Mitchell Engineering respectively. The additional plant went into service in 1958. The station had a final capacity of 240 MW, and three cooling towers.

In 1954 Wilge power station was started up, together with Taaibos power station. The two stations added 90MW to the capacity of the system and contributed over 100,000,000 units to the year’s output. This made it possible to reduce the hours of working of the older power stations on the Reef, thus the Rosherville, Brakpan and Simmerpan Power stations were used only as peak load stations.

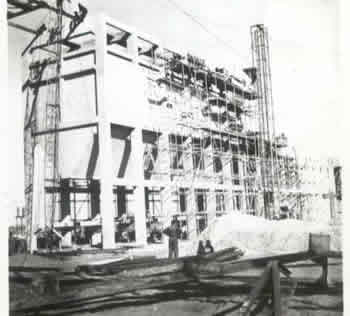

Views of the turbine house

OPERATING PROBLEMS

Wilge Power station was completed in record time, but not without compromising the performance and efficiency of the station. It was not uncommon for power stations to be built without a boiler house but the extreme weather conditions on the Highveld made it necessary for the boilers to be protected. Because of the haste in which Wilge was completed, the first eight boilers, initially, had no boiler house. This created a potentially dangerous situation and in later years a boiler house was added.

The urgency for an additional power station was such that it was decided to install boilers without economisers rather than wait for more efficient units. This had a negative effect on the output of the station. As early as 1957 the low load factor reflected the abnormal number of plant outages during the year. Modifications were made to several items of the plant and, on this account, the periods of outage for general overhaul were longer than normal. Non-scheduled outages were necessitated by problems caused by the induced draught fans and ducting, and with the automatic control gear on the boilers.

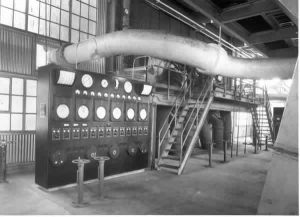

Views of the Control Room

STAFF FACILITIES

As with many other power stations operated by ESCOM, Wilge had an associated village, of which little is known. When the power station was converted to a training facility in 1991, there were conference and sport facilities as well as accommodation. The accommodation consisted of single quarters for the students and some of the staff members as well as houses for staff members with their families.

For schooling, the children of staff members either had to go to Ogies, a nearby village, or to Witbank for their secondary education. The staff and students also used the churches and shops situated in these two towns. The closure of the power station did not have a big impact on Witbank. Ogies, on the other hand, was slightly affected by the downsizing of the station that had already started in the 1970’s. The town was, however, still supported by the coal- mines and the farming community.

COMPARISION WITH OTHER POWER STATIONS

In order to meet the growing electricity demands, these power stations were enlarged from time to time. By 1959 however, Vierfontein, Wilge and Taaibos power station had been developed to the full capacities permitted by the resources available at those sites.

DECOMMISSIONING

In 1987 Kendal power station, not far from Wilge power station, was completed. The closure of Wilge, on completion of Kendal, was part of the agreement with the air-pollution authorities.

In the early 1980’s the growth rate for electricity consumption fell from 5,1% to 4% per annum.

In the first half of the 1990s there was hardly any growth in South Africa, and a negative growth rate was experienced in 1992. All new power station construction activity, except for Majuba Power station, ceased in 1994.

The older and less efficient power stations were mothballed or decommissioned. Wilge was closed in 1990 but was still used as a training station until its final decommissioning in 1995.

CONSUMERS

The Wilge power station supplied power to the Rand and OFS Region. Power from eight other power stations (Brakpan, Klip, Rosherville. Simmerpan, Taaibos, Vaal, Vereeniging, Vierfontein) was pooled to supply the various customers.

- City of Johannesburg

- Middle Witwatersrand Ltd

- City of Pretoria

- Pretoria Portland Cement Co

- Rand Water Board

- The Randfontein Estates GM Co Ltd

At Vierfontein it was decided to add four generators to the eight turbo-generators but only six additional boilers instead of seven, to the thirteen already installed and only one more cooling tower instead of two. Through careful testing the designers came to the conclusion that an extra boiler and cooling tower were not required. At other stations the same kind of testing was done in order to save money.

WILGE TRAINING POWER STATION

BACKGROUND

The idea of using a redundant operable power station for training comes from the Naval tradition of using a decommissioned ship for training. It is argued that though technology changes, the basic principles of operation stay the same. This approach exposes the students to situations as close as possible to those that would actually happen in real life.

POLITICAL CHANGES IN SOUTH AFRICA

In the mid 1980’s political changes started to take place in South Africa and the first tentative steps towards a democracy were taken. ESCOM’s staff composition, as many other state owned companies, consisted mainly of white males. In the field of training and development steps had to be taken to align the industry to the changing needs of the country. More non-whites and females had to be appointed in management positions and not merely as administrative or technical staff.

SUITABILITY AS A TRAINING STATION

Vierfontein power station initially provided training programmes but was decommissioned. These programmes were transferred to Wilge, and the Wilge training power station was officially opened on 22 March 1991 by the then General Manager Generation, Paul Semark.

Wilge was suitable as a training station since the equipment technology ranged from the 1950’s to the reasonably modern. This forced the students not to rely on modern technology only, which is mostly automated, but to become familiar with working and maintaining the older, manually driven, equipment.

Programmes providing maintenance and operating awareness were offered to graduate engineers. This enabled them to receive hands-on training, related to their academic studies. They received training in all aspects of the running of a power station, from generating power, maintenance, management and financial planning.

DISCIPLINES

At first, only Operating Courses for graduates and engineers were presented. However, various companies in the private sector were interested in specific training at Wilge and there was a demand from various Eskom groups and African States. Therefore, further programmes were developed and introduced.

Typical programmes were project planning, enhancement of existing plant operators, on-job supervisory skills, plant safety and first aid, turbine artisan training, on-job balancing, alignment, hydraulics, rigging and chemistry.

The duration of the programmes varied from four weeks of maintenance awareness, seven weeks of operating awareness to two twelve week sessions for operator development.

TRAINING TECHNIQUES

The training programme was called a Supervisory Skills adventure, with the emphasis on reinforcing leadership behaviour under real plant conditions, rather than simulated classroom exercises. The Wilge training power station was called the biggest classroom in the world, since the whole plant was the classroom, not only the lecture rooms and workshops.

The goal was to get an understanding of how a power station works at all levels. The programmes combined theoretical knowledge and practical work in operating and maintaining boilers, turbines and associated plant. Many of the operating programmes entailed shift work and emergency call-outs to maintain the reality of power station work.

Experiential learning was encouraged to enhance power plant performance whilst developing the individual and group competencies. Learning, rather than teaching was encouraged. The so-called “spoon-feeding” method was avoided. This did not imply that the study was not disciplined; working in a highly technical environment demands precision and dedication. The students were made aware of the possible implications of a wrong decision. Since they were operating in “real-time” (providing electricity to paying customers) the highest standard of performance was required.

Training and development were completely supported by all plant personnel. Staff members with years of experience assisted students in training and in that way their experience was passed on to the younger generation. Participants were therefore encouraged not only to find published information but also to learn from the experienced facilitators and maintenance staff. The students wore L-plates (special name tags) to identify them. These tags were removed at graduation.

The emphasis fell on self-study, but students were encouraged and assisted through group projects, a system of mentorship, guest speakers and discussion groups. The training was not only aimed at acquiring practical and theoretical knowledge but also that the students should become well rounded and be allowed to develop and discover themselves. Through presentations and discussion groups they were encouraged to express themselves and through teamwork projects and obstacle courses to develop their leadership skills.

STUDENT COMPOSITION

In 1991, out of a total number of 456 students of which 150 were residential, 58% were non-graduates, 33% were diplomates and graduates and 9 % did university bridging courses.

Participants were not only university and college graduates, but also ranged from experienced managers and operators to young people in transition from school to further education and training.

In 1991 32% of the students were artisans and 26% engineers. 18% did courses in statutory and safety, 10% management development, 9% did university bridging courses and 4% operator enhancement courses.

RACIAL DIVERSITY AND GENDER

The establishment of the Wilge training power station was ground breaking not only because of the way in which training took place, but also in terms of student composition. 21% were black students and 6% female. Over the next three years the percentage of black and female students showed an annual increase.

Students from other countries were also trained, some coming from countries with which South Africa previously did not have friendly relations. During 1991 the first group of operators from Electricidade de Mozambique received training at Wilge. Representatives from countries such as Zambia, Germany, Ivory Coast and Zimbabwe visited Wilge with a view to future training.

Through academic team projects, working night shift together, obstacle courses, sport events and discussion groups, bridging work was done. In their training the importance of teamwork in the operating and maintaining of a power station was emphasized.

Though the introduction of black, female and foreign students proved to be a great success, it did not come easily and required extreme dedication from both the students and staff. Though the political climate was changing rapidly, racial intolerance was still prevalent in the early 1990’s.

FACILITIES

Wilge had Single Quarters to house the students as well as some of the training staff. Mainly pensioners as well as some of the married staff lived in the village.

Seminar facilities were developed. The recreation club halls could house 100 to 300 people, Atken Park 50 to 200 people and the Guest House and Bowls Club 5 to 25 people.

Companies used the grounds to advertise products and services. The money earned from advertising contributed to the upkeep of the facility.

FINAL DECOMMISSIONING AS A TRAINING STATION

The main reason for the closure of the training station was given as financial. However, the station made a net income of R1,2 million in 1991, as compared with a net loss of R3,6 million in 1990. Overall the income increased by 75%. Some staff members who were actively involved in training programmes feel that because so many non-white students as well as students from countries with which South Africa at that stage did not have good relations, received training there, might have been seen as a threat by some.

The station finally closed in 1995 and was demolished.

STUDENTS

Kieswetter, Edward

Edward Kieswetter came from the Cape to the Witbank area, where he was appointed as training manager for ESCOM. He became a top manager in the Generation training power station. After the closure of the training station he moved to Megawatt Park. He worked for ESCOM for 8 years and 3 months, from where he moved to take a position as manager at First Rand Bank.

Govander, Thiva

Thiva Govander was one of the first students to start at Wilge training station. He studied Chemistry. After successfully completing his training, he joined ESCOM as a staff member. Today he is the manager of Kendal Power Station.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Wynne, W.D., Redundant operable power station and village used as a training centre. Paper presented at the Africon Conference 1992.

- Annual Report of the Wilge Training Power Station, 1991.

- Interview with W.D. Wynne

- Annual reports 1950-1995

- Megawatt Magazine 71; February 1979; September 1979; June 1981; October 1981.

- ESCOM Golden Jubilee, 1923-1973

- A Symphony of Power