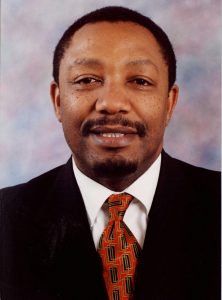

Thulani Gcabashe

Thulani Gcabashe – ESKOM CHIEF EXECUTIVE 2000 – 2007

Thulani Gcabashe joined Eskom in 1993 at the Durban Distributor during the time of Eskom’s ambitious and intensive electrification drive.

“I was a town regional planer working in Kwa Zulu-Natal during the late 80s and early 90s,” says Gcabashe. “During my travels, I came across Eskom teams doing electrification. That was very exciting to me, because often people speak of plans for the future or development that ought to happen, but here were guys who were not talking about it, but actually doing it. That really attracted me and there happened to be a vacancy for the electrification manager, so I applied.

“Eskom impressed me because it knew that a new society was bring created and instead of fearing change, it embraced it. In fact, the company started making changes even before it was told by government to do anything.”

Gcabashe soon made himself indispensable and within just two years he was appointed to run Eskom’s London office, moving from the Distribution Division to the Growth and Development Division in the process. Eighteen months into his three-year assignment Gcabashe received a call from Allen Morgan to inform him that the Electricity Council had just appointed him as Senior General Manager of Growth and Development. He eventually moved back to Distribution, but this time as a member of the national Executive Committee team. He held this position until 1999, when he was appointed Deputy CEO along with Bongani Khumalo. The following year, he became Eskom’s first black CEO.

Gcabashe had the difficult task of managing the utility and leading it forward during a time of change, while not completely doing away with had worked in the past. One of the big change factors affecting Eskom was the mount Grace Agreement, which was negotiated in 1999 by the Electricity Council, the Department of Public Enterprises and labour. The agreement laid out the future of Eskom.

“I was informed that the basic business of Eskom in generation and distribution remained, but that the new thrust would be to move into the commitment and diversify geographically,” says Gcabashe. “The other new imperative was to diversify the business and to take advantage of all our non-core operation to develop businesses.

“The one that stood out most was the Telkom system, which was largely built around protection and communication on our networks and which had the potential of becoming a major carrier of data and voice communication.”

Eskom Enterprises was created to house all the non-core operations and Gcabashe was appointed as its chairman.

“This created an interesting tension, because Eskom’s core business was seen as the boring staff members and Eskom Enterprises was seen as the sexy staff members that were always travelling. Guys were perpetually trying to jump the fence.”

“As far as the core business was concerned, Eskom was a mature business, so I did not want to make wholesale changes, but rather just tweak it as I went along.”

“However, I was involved in creating a new corporate identity for the utility. We succeeded in not destroying the essence and the past of Eskom, and instead we managed to give it an identity that spoke of a different future. We introduced open space at Megawatt Park, which allowed us to free up a entire block of the offices, which we could then rent to SARS”.

Gcabashe carefully arranged the entrance to Megawatt Park to reflect thid view. The Energy Statue was moved to the front of the new entrance and surrounded by a park inspired by the ancient city of Mapungubwe. This captured both the African heritage of the country and Eskom’s own legacy.

At the time, Eskom was one of the country’s front runners in the creation of a new and more equal society, but it did have to maintain a fine balancing act to ensure that the business remained profitable Government had decided that Eskom had to reduce the price of electricity in real terms until the end of 2000 to allow previously disadvantaged communities to gain a foothold in the new South Africa. Eskom was happy to absorb these costs for a period to enable new businesses to get their activities off the ground.

However, 2000 came and went with no intention from government to approve tariff increases, despite warnings from Gcabashe that if prices were not increased at the time, they would spike later. Other changes were also afoot during this time. In 2002 Eskom was transformed from a creature of statute to a company under the companies Act and appointed its first board. Board appointments were made by the minister and included international players, in line with the vision to globalize the company.

While government was still committed to the provisions of the Mount Grace Agreement, the board felt that it was time to shift the focus away from forays into Africa and to build additional plants locally. At the time, Eskom had a presence in 19 African countries.

“It was a tough time in my career, because government was saying one thing and the board another, but it was time to pull back,” says Gcabashe..” It was like turning the Titanic around and we did it by embarking on a transformation programme called Eyethu. It occurred to me that a turnaround of this magnitude cannot be achieved through discussions with the top 200 employees alone.

“We had not built a power station for many years and we had not been in project mode as a company for a very long time. It required a transformation process to take people along and change them. However, it was only 2004 that government rescinded the moratorium on construction. Because we could not build, we started to de-mothball all the mothballed power stations.”

In 2003, unit six at Camden was brought back to service as a pilot project. It soon changed from a project to a fully-fledged undertaking to bring the unit and the plant back to commercial service. Grootvlei and Komati power stations soon followed.

However, these efforts were not enough and it became clear that additional build was required. The steps Gcabashe took to get the capital programme off the ground prevented a crisis of immense proportions.

Eskom’s commitment to creating a better society not only focused on the country’s population in general, but also entailed a particular focus on bettering the lives of its own employees.

“We started to encourage each one of our employees to own a house. That is very i9mportant because for most of us, a house is the biggest investment we will ever make. It is an asset that can grow in value and e passed on to the next generation.

“Many of our workers would be accommodated in hostels ad would not want to build a house there, because they are from rural areas. In those days, banks would not fund homes in rural areas, but the Eskom Finance Company decided to do it. This was one of the ways in which Eskom tried to pass a dividend on to its workers and society.”

Although the present and the future will have many challenges, Eskom’s past provides the assurance of a future that would be unimaginable without Eskom.

Pull quotes:

”The company started making changes even before it was told by government to do anything.”

Thulani Gcabashe Gcabashe soon made himself indispensable and within just two years he was appointed to run Eskom’s London Office.

Eskom was one of the country’s front runners in the creation of a new and more equal society

“It was a tough time in my career, because government was saying one thing and the board another”

“We had not built a power station for many years and we had not been in project mode as a company for a very long time”

Thulani Gcabashe served as the Deputy Chief Executive, Chairman – Eskom Enterprises and finally Chief Executive.

Thulani has a Bachelor of Arts (UBLS) and a Masters in Urban and Regional Planning at the Ball State University (USA) ad has completed the Programe for Executive Development (IMD) at Lousanne Switzerland. He is also a member of the following professional bodies: The South African Planning Institute and South African Council of Town and Regional Planners.

Thulani began his career as a town and regional planner in Botswana in 1982. Between 1984 and 1992 he practiced with the Durban based firm of architects and town planners where he became a director in 1990. He joined Eskom’s Durban Distributor in 1993 where he served on the management team with the specific responsibility for Electrification. During 1995 and 1996 he served as the General Manager, Eskom International responsible for running Eskom’s London Office. During this period he attended the Programme for Executive Development at the IMD in Lousanne, Switzewrland. In 1997 he was appointed Senior General Manager (Customer Service) Distribution. Thulani has served on various boards of community-based organizations as well as companies outside his normal business engagements.