For South Africans living at the turn of the 19th century, the introduction of electricity must have been as exciting a development as the internet is to our generation today. But, like all new inventions and innovations, it took time before electricity began to impact people’s lives in a major way. The good townspeople of Kimberley were the first in Africa to experience the joys of electric streetlights (1882), and they even managed to beat London to it.

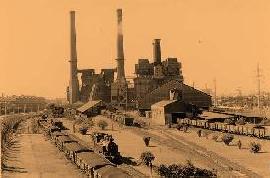

In 1886 an Australian prospector by the name of George Harrison stumbled upon a gold outcrop, in what is now Johannesburg, and declared a claim with the government of the Zuid Afrikaanse Republiek. Harrison is believed to have sold his claim for less than 10 pounds – but in any event he was not heard of or seen again. From then on mining was to be the main driver of development in South Africa as thousands of immigrants flocked to the city of gold seeking their fortune. Johannesburg grew rapidly –within five years of its existence it became South Africa’s first city to install an electricity reticulation system, which was powered by steam engines. This is remarkable considering that Cape Town is 200 years older than Johannesburg. Soon the mining companies realised that steam-generated power was inadequate for their needs and they joined forces to build small power stations to supplement the existing supply. In 1906 these smaller undertakings were bought out by the Victoria Falls Power Company (VFP) as the mining bosses sought large centralised power stations as opposed to small dedicated ones.

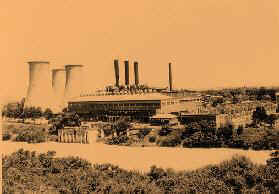

By 1915 the

VFP – so named because of its original aim to harness hydro-electric power from Victoria Falls – had built four thermal power stations (

Brakpan, Simmerpan,

Rosherville and

Vereeniging) with a total installed capacity of 160 megawatts. At around the same time, a system control centre was established at Simmerpan, which later developed into the ESCOM National Control Centre. Today, this Centre controls the national network, as well as the generating output of all ESCOM power stations. Meanwhile, in 1910, the Transvaal Colonial Government, realising the strategic importance of electricity, passed The Power Act. This piece of legislation defined electricity as a public service, and gave the government the power to expropriate private electricity undertakings after a period of 35 years.

From the earliest days of rail in South Africa, SAR (South African Railways) had been considering the idea of using electricity, as opposed to steam, to power the railways. In 1918 SAR invited a top London engineer by the name of Charles Merz to brief them on the matter. The Merz Report was submitted to Jan Smuts’s government in April 1920, which formed a committee to look into how South Africa should proceed with electrification. The findings of this committee led to the passing of the Electricity Act of 1922 which laid the foundations of the development of an electricity supply industry in South Africa to “stimulate the provision, wherever required, of a cheap and abundant supply of electricity”. From then on the South African electricity industry would be regulated, controlled, and ultimately run by a parastatal.

One of the principle authors of the Electricity Act was a certain

Dr Hendrik Johannes van der Bijl, a brilliant young research scientist whom the Smuts government had appointed to advise them on industrial development. It was van der Bijl’s vision that South Africa should take its rightful place among the world’s leading industrialised nations by 1) setting up a reliable, low-cost electricity power supply, and 2) establishing an iron and steel industry. It was partly thanks to his farsighted vision that the Government Gazette of 6 March 1923 announced the establishment of the Electricity Supply Commission (ESCOM), effective from 1 March 1923. Dr Van der Bijl’s passion for industrialisation was given free expression as he took up the reins as ESCOM’s first chairman. This great South African industrialist laid out exactly what he had in mind for his new-born infant.

“There lies before the Electricity Supply Commission a great task and a great opportunity. It will be our endeavour to play our part not as those who follow where others lead, but as pioneers; to foresee the needs of a country fast developing, and by wise anticipation be ever ready to provide power without profit, wherever it may be required.” (Dr van der Bijl)