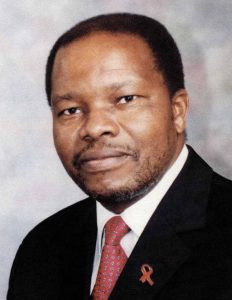

Reuel Khoza

Reuel Khoza – ESKOM CHAIRMAN 1997 – 2002

ACADEMIC YEARS

After earning his first degree, Khoza stayed on for an extra year to complete an Honours year as well. He had a passion for psychology and had a particular talent for African languages. He earned the grudging respect of the psychology professor by gaining an impossible 80% in the quarterly tests although his gift for literature and interest in music and poetry got him into trouble. After completing his Honours degree, he continued to teach at the university (as he had discovered a penchant for teaching and coaching). He soon found that he proved popular with the students. This admiration lost him his job when student activists appropriated several of his lyrics and poems to fan the flames of their protests against the iniquities of the time.

It caught the attention of the university authorities, too, and although he had not participated actively in the unrest, he was summarily cashiered.

BUSINESS CAREER

This sent Khoza into the business world, where he really wanted to be anyway. He first joined Unilever as a management trainee. This international corporation proved to be a great “university of life’. It ran a business appreciation programme for all newcomers, and Khoza, now a brand manager, attended its corporate development programmes. As enlightened as Unilever was, however, it was nevertheless not necessarily a meritocracy. When someone was promoted over Khoza’s head and he protested, he was effectively told that if he did not like the system, he could leave. He did. But he had tasted business at first hand and decided that he needed to build up a more practical academic base. He enrolled for a Master degree at Natal University, but was soon afterwards offered a scholarship by Shell to study at the University of Lancaster in the UK. Leaping at the opportunity to study abroad, Khoza completed an MA in marketing management in the UK and returned to Shell in South Africa as Shell’s marketing communications manager. Later, he also went to the Harvard Business School in the US, and the IMD (International Institute for Management Development) in Lausanne, Switzerland, where he completed advanced management programmes.

Very few companies in South Africa, apart from the internationals, were actively encouraging the development of black managers in the 1970’s. This led Khoza to swap the corporate world for the more challenging, but also more risky, career of an entrepreneur. He started his own consultancy at a time when there were many obstacles in the way of young and aspirant entrepreneurs, especially black ones. The business community in South Africa was a relatively small and exclusive club, often based on old-school ties. To rise above the crowded field, special effort was needed, and this was what young Khoza excelled in. He embarked on research work on corporate culture and built up a solid reputation for his meticulous surveys of, and research on, strategy, transformation, governance and corporatisation. He earned accounts from Ford, Firestone and his previous employer, Shell, and became a popular speaker and pamphleteer on a variety of subjects of interest to management development research, strategy, corporatisation and related areas. He started promoting a management philosophy of exclusivity based on strong values of Afrocentricity and ubuntu (an African philosophy stressing humaneness). He also became an active participant in various professional bodies such as the Black Management Forum, the South African Institute of Management and the Strategic Management Society of South Africa.

INTRODUCTION TO ESKOM

In 1986, Khoza was invited to attend one of the Top 30 meetings at Eskom, first as an observer and thereafter as a consultant. He had caught the eye of John Maree, Ian McRae and some of the other executives in the organisation, and was soon engaged in work relating to organisational development and projects concerning the non-payment problems in Soweto. He was therefore no stranger to Eskom and when the search for a successor to Maree started in earnest in 1996, he was introduced to Ms Stella Sigcau the then Minister for Public Enterprises as a possible candidate.

At the time, Khoza was a prominent businessman and chairman of a well-known pharmaceutical company as well as of an investment company (he had meanwhile sold the consultancy). He also held seats on the boards of about half-a-dozen other companies. When approached about the possibility of joining Eskom, he was intrigued by the possibility this held for practising what he had always been preaching in terms of business, management and leadership. Yet he was not keen to take on a full-time responsibility because of all his other commitments. A non-executive chairman role, as defined by John Maree, was therefore an added attraction. Like Straszacker, he was persuaded that there were plenty of competent mangers to run the business on a day-to-day basis, and that he would not be expected to get involved in the nitty-gritty detail. He also saw it, as many of his predecessors had, as some kind of national duty. Like his predecessors, too, he allowed himself to be persuaded by Thabo Mbeki (who was then Deputy President) and other influential members of the Cabinet to take on the challenge.

CHAIRMAN OF THE ELECTRICITY COUNCIL

He made an immediate impact at his first council meeting as chairman in March 1997. He welcomed the delegates and then reminded them – albeit very gently, although with little doubt in anyone’s mind that he was very serious – of their obligations towards Eskom. He stressed that council members had to work hard and set a good example for the organisation. He made it very clear that he would not tolerate absenteeism or a lack of punctuality at council meetings, and that he intended to be a strict as his grandfather – as well-respected community leader – had been in that regard. He was.2 Having laid down these grounds rules, he proceeded to run the large meeting like a long-time veteran.3

Since his appointment, he has brought many new perspectives to the organisation. He is, like his predecessor, a businessman, but with a different emphasis on many aspects that flowed from his background, studies, research and experience.

The Eskom that Khoza had inherited was radically different from the one John Maree took over 12 years previously. It was never easy to take the pulse of this giant, to see where the organisation stood. However, the legacy of Maree had given Khoza a ready scorecard to see how his new charge was doing in all the crucial areas. This had come about a few years previously at the instigation of the new government, which emulated the positive results that had flowed from the original price compact of 1991.

THE RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT PLAN

Soon after the 1994 election, the government published a Reconstruction and Development Plan (RDP), and demanded of each of the parastatals a set of then “RDP Commitments”. At the top of Eskom’s list was a further commitment to reduce the real price of electricity by 15% between 1995 and 2000. Since the original compact was still running, this commitment was translated into meaning an undertaking to reduce the real price of electricity by an additional 3% from 1997 to 2000.

Other RDP commitments were to electrify an additional 1 750 000 homes by the end of 2000,4 to embark on an aggressive affirmative action programme at managerial, professional and supervisory levels, and to educate and train employees and to upgrade their skills.

Eskom also undertook to “maintain transparency and worker consultation in decision-making”. It further undertook to contribute R50 million a year to the electrification of schools and clinics, and other community development activities. One of its very ambitious goals was to enable all employees to own a home. Small and medium enterprises would also be encouraged, and a set of specific environmental goals was adopted. Finally, Eskom undertook to finance its commitments to the RDP solely from its own resources and from overseas development funding.

Had Khoza used this scorecard to measure his new charge, he would have found that in most areas Eskom had fared well; it was a report card of which to be proud.

REDUCING THE REAL COST OF ELECTRICITY

The commitment to reduce the real price of electricity proved to be more difficult than was first thought. The price reduction was initially driven by a scaling-down in the capital expenditure programme, but pressure to reduce costs became ever greater. Despite optimism in 1995 that the price compact was on track, the cumulative real price reduction (since 1992) at the end of 1996 was only 16,8%, or 3,2% short of the promised 20%. Embarrassed, Eskom pointed out that it had achieved a 67% real price reduction since 1985 in spite of its huge electrification burden and the perennial problem of arrear debts. Nevertheless, a shift in gears was on the cards. In 1995, the vision shifted to ‘provided the world’s lowest-cost electricity for growth and prosperity’.5 As far as the RDP commitment was concerned, the price still had to be shaved by a further 6,8% below inflation. As inflation was dropping steadily, this proved to be a tough task. A! t the end of 1999, however, the goal was in sight; only another 0,7% was needed to meet the commitment. With the National Electricity Regulator having argued the Eskom price increase for 2000 down to 5,5%, Eskom would just meet the target if inflation ran at 6,2% or more. That was no mean feat – especially in the light of all the other commitments.

ELECTRIFICATION

Khoza was able to announce with pride that Eskom had met its RDP electrification target of 1 750 000 newly electrified homes more than a year ahead of schedule, having reached that total in November 1999. Since the start of its electrification initiative in 1991 until 1999, Eskom had electrified more than 2 135 000 homes in total, and had invested more than R7,5 billion in electrification projects.6

CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS

The Eskom Conversion Act was signed into law in 2002. This Act converted Eskom from a public enterprise into a public company having a share capital. The Minister of Public Enterprises, Mr. Jeff Radebe, announced the appointment of a Board of Directors for Eskom. The utility’s Board of Directors was appointed to preside over the affairs of Eskom Holdings Limited, the name by which the utility would now be known. The Board of Directors replaced the previous two-tier governance structure of the Electricity Council and the Management Board. Mr. Reuel Khoza was appointed as Chairman of the Board of Directors.

Notes

• Khoza channelled this talent into less-controversial areas as well; many years later he was to write the lyrics for several songs on Eskom. These proved to be as popular with the Eskom choristers as his earlier songs had been with his fellow students, though with a far more positive outcome for him.

• Khoza once took a senior councillor to task for arriving late at a meeting without prior notice. When the excuse was offered that the councillor had been held up by the traffic, Khoza refused to accept the apology, pointing out that everybody else who used the same road had managed to be on time.

• There were normally about 20 councillors, plus 10 members of the Management Board at the council meetings. To conduct a meeting of this very large and diverse group in a constructive and productive way was no mean task even for a seasoned veteran such as John Maree.

• Both RDP targets and Eskom’s own targets were sometimes not clear on exact time span. “From 1995 to 2000” was often interpreted as running from 1 January 1995 to 31 December 2000 (six years). As Eskom had already entered into a price compact and an electrification plan of its own, there was sometimes confusion about these overlapping targets.

• And claiming that South Africans enjoyed the cheapest electricity in the world. This has always been a controversial topic; living standards, incomes and wages, exchange rates and a host of other factors make this a true minefield to define, just like “all” in “electricity for all”. Despite the controversy, and perhaps because of it, it made a good rallying point and therefore a good vision statement. Allen Morgan detested this vision being translated in terms of Eskom being “the cheapest” electricity producer in the world. “Eskom”, he said, “will never be called cheap”.

• This was equivalent to a further 30% reduction in the real price of electricity over the period.