From the start there were challenges in getting the most out of Kriel, which was once ESCOM’s biggest power station. The boilers were susceptible to slagging, and new mill foundations had to be built when the heavy milling machinery created dangerous vibrations. On completion, in 1979, Kriel consisted of 6 sets of 500 MW each and was one of the largest coal-fired power stations in the southern hemisphere, as well as being of the world’s first to receive its coal from a fully mechanised coal mine.

Meanwhile,

Duvha, like

Kriel, was a ‘six-pack’ power station with separate housing for its turbine generators. Unlike Kriel the boilers were of a conventional design and used natural circulation and not once-through. Kriel began commercial operation in 1979 and on completion (in 1983) boasted six sets of 500 MW each. It was distinctive for its boiler house superstructure; constructed from concrete in order to reduce lead time and capital costs amidst a world shortage of steel.

Duvha Power Station was the third and final ‘six-pack’ and was built near Witbank in Mpumalanga. It, too, used a ‘once-through’ boiler technology, but instead of six 500 MW sets it consisted of six 600 MW sets. The boilers proved more reliable than Kriel’s, but there were still challenges, particularly of an environmental nature. The precipitators on Duvha’s first three units did not reduce emissions to acceptable levels and the pollution problem was only solved in 1984 when the offending units were retrofitted with pulse jet fabric filter plants – a world first. Another first for Duvha came in the form of a man by the name of Mr Ehud Matya – ESCOM’s first black power station manager: but that’s a story for a later edition.

In the 1970s ESCOM’s environmental challenges paled into insignificance compared to the crisis that it faced on 5 December 1975. An interconnected transmission system, while preferable, had its risks, and faults could spread to the entire country. This is exactly what happened on that particular day, when a relay malfunctioned at the Hydra Substation near De Aar. Much of the country went without power for 24 hours, and ESCOM had to rethink its transmission system. In 1976 ESCOM addressed the problem by building two gas turbine stations, one near Cape Town, the other near East London.

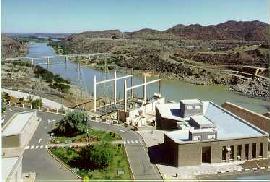

1976 saw the completion of Hendrina power station and Gariep (then Hendrik Verwoerd) hydro-power station, (Arnot had been completed the previous year).

ESCOM itself was not a capitalist enterprise and in the 1970s many South Africans began to see it as inefficient, especially when the price of electricity started to rise. The problem was that ESCOM had to finance most of its own growth. At the same time ESCOM feared that if they did not expand the country would run out of power. In 1977 consumers were paying 166% more for electricity than in 1971. Unsurprisingly, the move to Megawatt Park in 1977 was not greeted favourably by the public who saw it as an example of ESCOM’s wasteful expenditure. The upshot of all this was that in 1977 the Minister of Economic Affairs asked the Board of Trade and Industries to investigate the supply of electricity in South Africa.

ESCOM co-operated with the board to seek out the best solution for the utility and for the South African economy. In the end ESCOM did away with the Central General Undertaking (CGU) and modernised its accounting system. Although the Capital Development Fund (CDF), and ESCOM’s insistence on large reserve plant margins, came under attack, they were ultimately defended by the government, who shouldered some of the blame for the sharp price increases. ESCOM defended its spending on expansion by arguing that without it South Africa would have faced not only an oil shortage crisis, but an electricity shortage crisis, too. In 1979

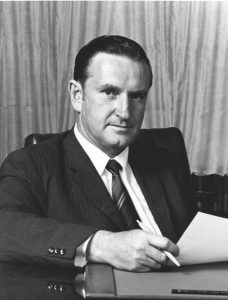

Jan H Smith, ESCOM’s General Manager at the time, lambasted the Board of Trade and Industry for their use of the word ‘profit’. Then, as now, the term is a potentially misleading one, given that ESCOM’s profits do not enrich private investors but are used to expand South Africa’s electricity system.

In 1980 the Chairman of ESCOM,

Reinhardt Straszacker, retired and it was the same Jan H Smith who grasped the baton. Smith, who raised tortoises as pets, because he admired their tenacity as he was known for being a ‘man in a hurry’. He was nicknamed ‘Mr Kilowatt-hour’, a reference to his ability to reduce complex planning issues to the effect they would have on the cost of a Kilowatt-hour of electricity.