Kendal was the world’s largest indirect dry-cooled power station, boasting chimneys 275 m high. After Kendal came Majuba power station (another dry-cooled giant), which first went into service in 1996 and was only completed in 2003. In those intervening years, as Eskom focused on electrifying the country and on coming to terms with its new political masters, there was very little work done in the way of new generation. In 1993, it was announced that Allen Morgan would take over from Ian McRae as Chief Executive. Morgan is described, in “A Symphony of Power”, as “a distribution man through and through”. He is also, in the same book, described as “a people person” and “a staunch advocate of Eskom’s electrification programme, which he regards as pivotal in the developing society for improving the quality of life and enhancing the potential for small business development”. Morgan’s thinking was certainly in line with that of the new government. With democracy came huge political pressure to bring electricity to the people … all of them. The word “power” has various connotations – and in South Africa, it was used to galvanise support against apartheid, usually in the phrase “power to the people”, or “Amandla – Awethu

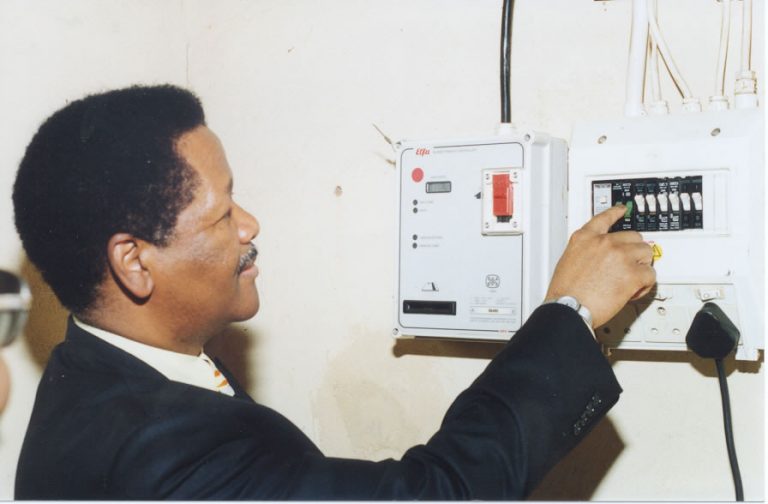

In the 1990s, Eskom made a herculean effort to play its part in bringing power to the people. In 1993, there were 300 000 electrifications countrywide (two-thirds done by Eskom and a third by various municipalities). By 1995, the combined (both Eskom and municipalities) number of connections was 450 000, and in 1997, it was half a million. If you assume that the average family consists of six people, then, every year, some three million South Africans were being connected to the grid and enjoying the improvement in living standards that went with it.

However, putting millions of poor people onto the grid creates its own problems; for a start, how are these people expected to pay for the service? To make matters worse, in 1994 (besides committing to electrifying 1.75 million homes by 2000), Eskom had committed to bringing down the real price of electricity. What did not help matters was that Eskom’s Distribution business was fractured, with wide disparities in cost, tariffs, and service levels. To think that there were over 120 municipalities, each with fewer than 1 000 customers. Many of them were in poor financial shape, and many used the sale of electricity to raise funds. There were also disparities in what customers paid for electricity: for example, mines in Gauteng got their power more cheaply than those in Mpumalanga, even though the latter were closer to the power stations. In short, apartheid had made a mess of local government and service delivery, including the service of electricity.

With a new democratic order, local government became more integrated, that is, poorer black townships were combined with wealthier (formerly) white areas to form transitional local councils (TLCs). There was massive political pressure for the poorer areas to catch up with the richer ones (in terms of services), but there simply was not enough money to pay for it. As municipalities (particularly smaller ones) ran out of cash, they defaulted on their Eskom bulk accounts. Eskom offered to take over distribution in certain municipalities, but the offer was rejected, as, for municipalities, the sale of electricity was (and still is) a lucrative generator of much-needed income. The more things change, the more they stay the same. Eskom proposed that, at the very least, municipalities had to de-link electricity cost and supply from other services and start charging cost-reflective tariffs. The state of municipal distribution was a hornet’s nest, involving the competing (and sometimes intersecting) interests of municipalities, town councils, civic groups, provinces, and the big mother ship … Eskom. Something needed to be done.

In the early 1990s, Eskom knew which way the political winds were blowing and had begun serious discussions with the ANC on the future of the electricity industry. It ignored protestations (and governmental decrees) not to engage the ANC, and talks led to the inauguration of a National Electrification Forum (NELF) in September 1993. The NELF did not have any real power to make policy, and inevitably, it became a talk shop. It disbanded itself in 1995, but not before submitting a final report to government. The report argued that there were too many distributors and proposed that the smaller municipal undertakings had to merge with Eskom. It also proposed that a National Electricity Regulator (NER), with broad powers to regulate the industry, had to replace the Electricity Control Board and that its first task had to be to implement the findings of the NELF.

Eskom came up with counter proposals on the thorny issue of distribution: consensus on the matter was proving elusive. Less controversial was the idea of a National Electricity Regulator, which was established towards the end of 1994. In 1995, after an amendment to the Electricity Act, it replaced the Electricity Control Board and was given sweeping powers to regulate the electricity industry.

Perhaps it was hoped that the NER would mediate competing interests and come up with a solution to the distribution problem. Municipalities were aggrieved that Eskom’s own distributors paid less than they did for electricity. On the other hand, Eskom wanted the municipalities to separate their electricity undertakings from the rest of their services.

In late 1994, Thabo Mbeki (Deputy President at the time) was making noises about privatising state assets. Public enterprises and unions were required to set up committees to look into “restructuring”. Nothing came of it, and nothing came of the recommendations of the government’s own restructuring committee, known as ERIC. Although everyone agreed that the industry needed to be restructured to ensure its financial sustainability and to move towards a fair (if not completely cost reflective) pricing system, consensus could simply not be reached. It is difficult to say whether this was one of the main causes of the 2007 debacle when the country ran out of power, but when Eskom needed to be putting up power stations, it was bogged down in an intractable wrangle over distribution – and all in a climate of pressure to electrify millions of households.

It also did not help that the NER, which should have been making the tough political decisions and driving change, lost its Executive Chairman (Ian McRae) in 1997, to be replaced by Magate Sekonya, whose reign coincided with the rapid decline of the NER. After he was got rid of, it was decided to separate the positions of Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive, and in 1999, Dr Enos Banda became Chairman and Dr Xolani Mkhwanazi Chief Executive. Eighteen months of valuable time was lost in the process, and still the much-needed restructuring did not take place – and to compound it all, non-payment was reaching crisis proportions. In 1994, Eskom was owed R920 million in arrears, and by 1999, Eskom’s customer arrears (which included individual customers as well as municipalities) stood at R2 billion. It would take some years to sort out the problem and help municipalities reverse the tide of non-payment. To this day, there is controversy around the distribution of electricity and the levies municipalities put on electricity charges. However, currently, municipalities account for over 40% of Eskom’s sales – and Eskom works closely with them on a range of issues, including payment arrangements and energy saving.

In 1997, John Maree retired as Chairman, to be replaced by Eskom’s first black Chairman – Reuel Khoza. Khoza was (and still is) many things: an intellectual, a businessman, a linguist, a humanist, a composer and lyricist, and an entrepreneur. In the 1980s, he consulted to companies on issues of management development, strategy, and corporatisation. He was perhaps one of the first South Africans to talk about an African philosophy of management, a philosophy that stressed human values and, particularly, the value of connectedness – or Ubuntu.

In 1986, he began attending the Eskom Top 30 meetings, first as an observer and later as a consultant. John Maree and Ian McRae saw him as a reliable and credible mediator between the black and white worlds of a rapidly changing South Africa. Perhaps it was Khoza’s love of music and languages that had blessed him with a finely tuned ear; he was a good listener who was open to different opinions. He also placed a high value on lifelong learning and improvement. These qualities would come in handy over the ensuing years, as Eskom sought to transform itself.

Amid many unsolved issues of restructuring of the industry and the problems of distribution, the government set Eskom a range of goals: reduce the electricity price (by 15% between 1995 and 2000), electrify 1.75 million homes (by 2000), implement a far-reaching programme of affirmative action, and upgrade the skills of employees. Further, Eskom also undertook to operate the business in a spirit of transparency and even to consult workers in decision making. Those were indeed the heady days of democracy.

Eskom showed the government that it was serious about transformation by delivering on these commitments. By the end of 1999, almost half of all managerial, supervisory, and professional staff were black, coloured, or Indian. In 1995 alone, the organisation created 500 small, medium, and micro enterprises (SMMEs), and in 1999, it spent almost R1 billion on black-empowered companies. On the training front, Eskom dramatically increased the literacy of its workers and supported thousands of bursars and trainees (for example, there were 480 black bursars and trainees who graduated in 1999).

The organisation also committed itself to helping employees buy their own houses; by 1999, the recently created Eskom Finance Company had loaned out R2.2 billion to home buyers. It is easy to gloss over the figures and to bemoan the “lack of real change”. The fact is that people’s lives were being transformed in ways difficult to imagine for those used to First-World comforts. The veteran journalist and author Allister Sparks put a human angle on the government’s programme of social uPliftment in his book Beyond the Miracle: Inside the Eskom’s eighth decade “Powering transformation” March 2013 Edition 34 Page 21

Did you know!?

• Majuba power station (fully operational in 2001) is the only power station in the world that combines wet and dry cooled technologies.

• On commissioning in 1993, Kendal power station became the world’s largest indirect dry-cooled power station.

• In 1997, Reuel Khoza replaced John Maree as Chairman of the Electricity Council, making him Eskom’s first black Chairman. In 2002, when Eskom became a public company, Reuel Khoza was appointed Chairman of the Board of Directors.

• In 2002, construction began on the Klipheuwel Wind Facility in the Western Cape. These were the first wind turbines in sub-Saharan Africa.

• The Eskom Conversion Act was signed into law in 2002, which meant Eskom ceased being a public enterprise, and became a public company with share capital.

• After the 1994 elections the government set Eskom the target of electrifying 1 750 000 homes by the end of 2000. The target was reached with a year to spare.

• Reuel Khoza (Chairman from 1997 to 2005) wrote the lyrics for several songs about Eskom, which were performed by Eskom choristers.

• In 1999, Eskom achieved its employment equity target of 45% black staff in managerial, professional and supervisory positions.

• In 2000, Thulani Gcabashe replaced Allen Morgan and became Eskom’s first Black Chief Executive.

• Eskom published its first glossary of energy terms (English/ Sesotho/Sepedi/IsiXhosa/IsiZulu) in 2001. It was authored by Sipho Neke, Rose Diale, Zama Bekeweni and Nto Rikhotso.

• In 2001 Kumo Radebe was appointed to head up Matimba Power Station, thus becoming Eskom’s first female power station manager.

• In 1993 the Electricity Council became much more representative of Eskom’s stakeholders when 3 members were appointed to represent the unions, and two black women were appointed: Ellen Kuzwayo and Nozizwe Majija.

• In 1993 Dawn Mokhobo was appointed Senior General Manager of Growth and Development – the first such senior appointment of a woman in Eskom, black or white.

• Allen Morgan, who became CE of Eskom in 1994, was (from 1983-1985) the Western Cape Region’s Eastern Distribution manager, and the Hex River Power Station manager. Thus he was the only person in Eskom to hold the job of distribution manager and power station manager simultaneously. 1993 to 2003 New South Africa. In it, he quotes a Mrs Malala, whose life has been greatly improved by electricity and indoor plumbing. She has more time for leisure, she can refrigerate her food, and she can watch television. As Mrs Malala says, “I have got time to rest and I’ve got more time for my church work”.

As it turned out, Eskom reached the magic number of 1.75 million connections in 1999 (a year ahead of schedule), and it also managed to bring down the price of electricity, so that the government could proudly proclaim South Africa as having the cheapest electricity in the world. Eskom certainly was playing its part in giving hope to a people who were longing for release from the bonds of poverty.

Eskom’s leadership understood that the organisation needed to put its considerable resources to work in making a real difference to those living on the margins of what was an unequal economy. In 1998, the Eskom Development Foundation was established to integrate the organisation’s various CSI initiatives, including small business development and the electrification of schools and clinics. In 1999, Reuel Khoza could announce that, in the 90s, his organisation had spent R800 million on social investments. But it was not all good news, for it was around this time that Eskom made submissions to government that, unless there was some rather urgent and large investment in new power stations, the country would experience electricity shortages in 2007. One of Maree’s major drives, and something continued by Khoza, was efficiency. From 1985 to 1995, the ratio of gigawatt-hours (GWh) sold per employee rose from 1.7 to 2.7. In 2000, it was up to 5.1 GWh sold per employee. In 1983, Eskom power stations had a unit capability factor (UCF) of 72%. The UCF measures a power station’s availability and gives an indication how well plant is operated and maintained. This 72% was not a good rating, and although it had improved to 80% in 1993, it needed to get a lot better for Eskom to achieve its goal of world’s lowest-cost producer of electricity. Under the guidance of the Executive Director of Generation, Bruce Crookes, Generation set itself the target of 90:7:3 – 90% availability, 7% planned outages, and 3% unplanned outages. In 1998, Eskom’s UCF hit 92.7%; plant efficiency was up, and there was a large reduction in water usage (down to 1.25 litres a kWh).

Reuel Khoza and Allen Morgan were showing that it was possible for South Africans to work together in a spirit of understanding and mutual benefit. Racism and resentment were dead-end streets that would condemn the country to more strife.

In 1997, Eskom’s management, in the spirit of national healing and nation building, and with much encouragement from Reuel Khoza, made a submission to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). The submission covered the years from 1960 to 1994 and made it quite clear what Eskom’s mistakes were: “Until the late eighties, Eskom did very little to improve the plight of black people in South Africa … As an employer, its employment practices were largely discriminatory.” Eskom even went so far as to acknowledge some guilt in the injustices of apartheid. The organisation apologised to all South Africans for “not taking active steps to facilitate the demise of apartheid and racial discrimination. Also, for not using its links with the government to influence its thinking and apartheid based policies”. With the advent of democracy, a refreshing change of attitude came to Africa. Reuel Khoza, along with many other captains of industry, saw Africa (and its lack of development) as a major opportunity. In 1995, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) established the Southern African Power Pool (SAPP): a common grid and a common market for electricity in the region. The year 1996 saw the commissioning of a transmission line from Matimba power station (in Limpopo province) to Bulawayo in Zimbabwe; the line supplied much-needed electricity to both Botswana and Zimbabwe. That same year, Eskom entered into a partnership with Electricidade de Mozambique (EdM) and the Swaziland Electricity Board to construct two 400 kV transmission lines from Arnot and Camden power stations to a substation near Maputo. The lines would supply the Mozambique Aluminium Smelter (MOZAL), which was founded in 1998 and is currently the second largest aluminium producer in Africa.

South Africa’s (and Eskom’s) increasing integration into Southern Africa created various opportunities. Eskom’s services were in demand, and there were partnerships on projects in Tanzania, Mozambique, Zambia, and Namibia. Reuel Khoza was excited by the opportunity to leverage the scale and capability of Eskom to help unlock Africa’s growth. He wanted to position Eskom as the “pre-eminent African utility with global aspirations”.

At around the same time, Eskom was dealing with the issue of whether to privatise certain Eskom services not directly related to the core business of providing electricity, for example, IT, construction, aviation, and the servicing and maintenance of equipment. In 1999, Eskom Enterprises was registered as a wholly owned subsidiary of Eskom and would focus on Eskom’s non-regulated business activities in South Africa, as well as look for opportunities to do business on the rest of the continent. Reuel Khoza now had a vehicle to help Eskom make the most of the opportunity of South Africa’s integration with Africa.

Khoza’s vision was crystallised into a strategic intent “to be the pre-eminent African energy and related services business of global stature”. In its first year, Eskom Enterprises exchanged business contracts with a host of African countries and identified opportunities in hydropower, mining, refurbishment of turbines, and the upgrading of power systems.

In late 1998, the government showed its intention to restructure the energy industry by releasing a White Paper (an authoritative report that commits the government to certain policies) on a comprehensive energy policy. The White Paper answered some key questions around Eskom’s function and identity, namely, “Who owns Eskom?”, “Should Eskom pay taxes and dividends?”, and “How should the electricity supply industry be structured?”. The Eskom Amendment Act took its cue from the White Paper and was passed at the end of 1998, making Eskom a limited liability company with share capital and falling under the Companies Act. This conversion of Eskom took effect in 2002 when the Eskom Conversion Act was signed into law. Eskom was now run not as a public enterprise, but a public company with share capital. A Board of Directors was appointed by the relevant minister to replace the two-tier governance structure of the Electricity Council and the Management Board. This Board of Directors now presided over the affairs of Eskom Holdings Limited (Eskom’s new official title). Reuel Khoza was appointed Chairman of this Board.

Meanwhile, in 2000, Thulani Gcabashe had been chosen to succeed Allen Morgan, who was retiring, as Chief Executive, with effect from April 2001. Gcabashe had been with Eskom since 1993 and was responsible for the electrification programme in KwaZulu-Natal. He then ran Eskom’s London office, before becoming Senior General Manager for Customer Services.

He joined the Management Board and Electricity Council in 1999. Allen Morgan left the company with a parting gift – the publication “A Symphony of Power”. These articles in Eskom News have relied heavily on this book, which was written by Jac Messerschmidt and Steve Conradie (both former employees of Eskom).

Eskom’s efforts to electrify the country did not go unnoticed on the world stage, and in December of 2001 at the Global Energy Awards ceremony held in New York, Eskom was presented with the Power Company of the Year Award. That same year, Eskom embarked on a makeover; a new corporate identity and logo were approved in 2001 and implemented in 2002. South Africa’s integration back into the world had its benefits, and in 2002, Eskom co-hosted the World Summit on Sustainable Development, which was held in Johannesburg. The summit brought together tens of thousands of international participants drawn from governments, NGOs, businesses, and other groups to focus attention and action on meeting the world’s challenge to improve lives and conserve natural resources. Eskom had a role to play beyond simply providing electricity, and the leadership of the organisation was aware that its aims and goals were aligned to those of Government. The idea of leadership and, particularly, African leadership was a matter close to the heart of Reuel Khoza, so it was apt that Eskom should throw its weight behind the new African Leadership Programme. In 2002,

President Thabo Mbeki inaugurated this Eskom sponsored programme when he unveiled bronze statues of Oliver Tambo, Robert Sobukwe, Steve Biko, and Nelson Mandela at Megawatt Park. Those statues stand in the atrium of Megawatt Park and serve as a powerful reminder as to how far the country, and Eskom, have come in the past few decades.

Work begins on Ingula, Medupi, and Kusile – but it is too late to stave off power interruptions as Eskom struggles to keep up with demand; there is a shuffling of leadership positions before things settle down; a line in the sand is drawn; and the organisation restructures for a shift in performance and sustainable growth.