In 1951, America’s Atomic Energy Commission proved that it was possible to generate electricity from nuclear energy using uranium for fuel. This sparked international demand for uranium, which is found in the same ore structures as gold, and meant that South Africa’s sophisticated gold-mining industry was in a good position to exploit this valuable by-product. But extracting uranium is an energy-intensive business, and ESCOM was called on to beef up the

Rand Undertaking. ESCOM’s answer to the plea for more power was to build Wilge power station at Ogies on the Witbank coalfields – and to build it at record speed! Such was the haste of the construction that they did not bother to build boiler houses ,which meant that the first eight boilers stood exposed to the elements.

Thanks to its abundant reserves of uranium, South Africa was drawn into the international nuclear community, and the government sought to make the most of the situation.

From 1954 onwards, ESCOM’s Chairman,

Dr JT Hattingh, sat on numerous committees that investigated the possibility of using nuclear energy for industrial purposes. Although there were plenty of interest and enthusiasm for nuclear energy at the time (similar perhaps to the current push for renewable energy), Dr Hattingh remained phlegmatic. He retained this cautious approach to nuclear power throughout his tenure as Chairman and instead pushed ahead with unprecedented expansion to South Africa’s coal-powered generation fleet.

When, in 1957, the Special Commission into the Application of Nuclear Power asked him whether ESCOM ever deemed it necessary to implement power cuts due to a shortage of coal, his answer was “No”.

The Chairman did not take into account the fact that coal mining for the supply of South Africa’s voracious power stations came at a terrible price paid in human lives and limbs. The accident rate in South African coal mines was one of the highest in the world. On 21 January 1960, 431 miners were trapped when a large chunk of the Coalbrook North section of the Clydesdale Colliery in the northern Free State collapsed. Highveld and Taaibos were entirely dependent on the Clydesdale Colliery, and so emergency measures were undertaken to get them running at full steam. Although ESCOM managed to avert any major disruption to the network, the human cost was staggering.

A Mining Safety Committee was formed, and it did indeed put safety first by closing down dangerous collieries – which meant significant cuts to the power supply. Consumers had to make do with less, and the goldmining industry took a big hit.

Meanwhile, the attitude of the State towards the majority of the country’s citizens was causing increasing upheaval. The Defiance Campaign began in 1952, followed by the adoption of the “Freedom Charter” in 1955. In March 1961, the recently formed Pan African Congress (PAC) protested against the hated pass laws, which severely limited the freedom of movement of African people. Protests spread throughout the country, though the government was not ready to undo apartheid just yet.

Fortunately for ESCOM, the ANC and the PAC did not perceive South Africa’s power utility as a legitimate target, and so, for the moment, things carried on more or less as normal. “Normal” was, in this case, rather extraordinary, as ESCOM achieved extraordinary growth. From 1952 to 1959, eight new power stations went into commission:

Hex River,

Vierfontein,

Umgeni,

Wilge,

Salt River 2,

West Bank 2,

Taaibos, and

Highveld. Additional capacity was added to Central,

Colenso, Klip, Vaal,

Vereeniging, and

Witbank.

The first power station to be commissioned in 1953, was situated in the Free State and supplied both the Klerksdorp/Kimberley area and the Free State goldfields – three generators dedicated to the former and the remaining nine to the latter. Cape Town received a boost to its supply when Salt River 2 began operations in 1955. East London’s West Bank 2 added 85MW to that town’s supply in 1956.

It became apparent that, with the bigger power stations, the standard generator size of the time had to be upped from 30MW to 60MW.

This necessitated switching to pulverised fuel (PF) firing. Although PF had been used in

Congella in 1928, the performance of the station was compromised by what was really experimental technology. But PF technology had matured by the 1950s and was used in the second phase of the Wilge power station. It was also used in Taaibos and Highveld power stations. Taaibos, commissioned in 1954, was situated in Sasolburg in the Free State and was built to satisfy the growing industrial demand in the Vaal Triangle. Highveld, adjacent to Taaibos, was commissioned five years later and, like Taaibos, boasted an installed capacity of 480MW. Increased transmission was necessary, as ESCOM sought to supply the Free State goldfields with electricity from the Taaibos/Highveld complex. New technology allowed for higher transmission voltages, and 275kV (the standard at the time was 132kV) was decided on. This meant that ESCOM could use 300kV class international standard equipment, rerated for an altitude of 1 500m.

In 1945, ESCOM’s total generating capacity was 1 217MW; by the end of 1954, it was 2 052MW; and by the end of 1959, it had increased to 3 297MW – a growth of 170% in 14 years. It was an astounding achievement for ESCOM and allowed South Africa to benefit from international demand (driven by the post-war economic boom) for its commodities.

Not only did ESCOM grow its generation capacity in the 1950s, but it also interconnected power stations and extended its transmission system. Furthermore, by March 1961, ESCOM had another 1 265MW of generating capacity on order. By 1960, ESCOM had also extended its supply area to 191 100km2. The development of new transmission technology meant that ESCOM was now able to send blocks of power overlarge distances and could save considerable amounts of money through pooling. Hence, in 1955, generation on the Rand, Eastern Transvaal, and Cape Northern undertakings was pooled. The Natal Southern and Central undertakings were also pooled that same year.

Another development of the 1950s was the demand from municipalities, many of whom abandoned expensive local generation and bought bulk from ESCOM. In 1945, ESCOM sold 565 million units of electricity to municipalities, and by 1955, that figure had jumped to 2 051 million units.

ESCOM needed more office space, and in 1958, the organisation’s head offices moved to

ESCOM Centre in Braamfontein. It was only 2km from the city centre; yet many people felt as if ESCOM was moving “into the wilderness”. But soon afterwards, Braamfontein became a bustling business district, and ESCOM’s move proved prescient. In 1962, JT Hattingh had reached the end of his term, and ESCOM needed a replacement.

Professor Reinhardt Ludwig Straszacker had been a member of ESCOM since 1952 and was well versed regarding the organisation, although he was aware that, as Chairman he would be entering what was for him, as a scientist, uncharted territory: “The engineer must bring the analytical elements into a whole, which is more than the sum of the individual elements. The analytically-inclined person has got to fight for coming back to the synthesis, because the elements themselves are not the end results.”

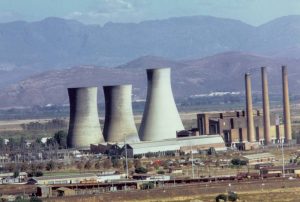

Straszacker would oversee some momentous changes in the organisation, as ESCOM embraced innovation and technology like never before. The start of his tenure coincided with the commissioning of Komati power station. After detailed investigation, it was decided that the abundance of coal in the Highveld of Mpumalanga province (then Eastern Transvaal) made it an ideal area to replace the Vaal Triangle as the centre for generation. Komati power station was situated between Bethal and Middelburg and got its name from the Komati River, although its water, in fact, came from Nooitgedacht Dam 65km away. Komati’s first unit came online in 1962, and it was completed in 1966, boasting five sets of 100MW each and four of 125MW each, with a final capacity of 1 000MW.